Architects Now Doubling as Developers

Originally published by the New York Times on 07 February 1988. Written by Shawn G. Kennedy. Access article here.

Even after construction crews completed work two years ago on Riveredge, an office complex in Florham Park, N.J., plenty of work remained for Edward Blake and Donald Rotwein, who served as the project’s architects.

There were the major concerns of attracting tenants and what to charge them. And then there were such details as keeping the tenants warm enough in the winter and keeping the lawns in shape. For the architects not only designed Riveredge’s two buildings, but they also served as the developers. In addition, their firm is managing the 245,000-square-foot complex.

The principals of Rotwein & Blake, which is based in Union, N.J., are part of a widening circle of architects and architectural firms venturing into development without giving up their architectural practices.

They are motivated, they say, by the desire to exercise more control over their designs, generate business for their firms and make more money.

The development end of the real estate industry has long had many trained architects among its practitioners. But until recently many in the architectural community have considered design and development mutually exclusive endeavors.

”The feeling was that design was art and development was business and that architects could not serve two gods,” said Mr. Blake. ”But more of us are seeing the profession for what it is – a business. Good design and honest work are not compromised because the architect has more responsibility for a project.”

John Burgee, who has been in partnership with Philip Johnson for more than 20 years, reflected the traditional viewpoint on the subject when he said:

”It seems to me that there is a basic conflict between the role of the architect and that of the developer. The architect’s goal is the design of a good building. The developer’s aim is to make a profit. I believe that it would be difficult for the same person to keep track of good design and the profit objective and do justice to both.”

But Mr. Burgee acknowledged that he and Mr. Johnson, whose designs in Manhattan include the world headquarters for A.T.&T. with its Chippendale top and the elliptical structure at 53d Street and Third Avenue known as the ”lipstick building,” had at one time given some thought to developing on their own.

John Portman, the architect based in Atlanta who is best known for the large hotels his firm has designed and built, perhaps epitomizes what appears to be a growing trend in the profession. But for a time he was regarded as a renegade by some in his profession because of his aggressive pursuit of both architecture and development. Mr. Portman recalled last week that in 1968, just as he was about to give a talk at a meeting of the American Institute of Architects, the professional organization to which most of the country’s practicing architects belong, he was called before the organization’s board of directors.

”The discussion centered on whether it was proper for me to be in development,” said Mr. Portman, whose projects include Atlanta Regency with its 23-story lobby. ”Tradition says the architect is just to provide a service to a client. But my question was: ‘When the architect becomes the developer and is thus the client, does the potential for conflict of interest mean that he puts himself in the position of cheating himself?’ ”

Mr. Portman, who has been a member of the A.I.A. for 30 years, said that since that discussion his development activities have not been questioned by the organization.

Today more of his colleagues seem eager to follow in Mr. Portman’s footsteps.

LAST April, at its annual meeting in Washington, the A.I.A. held a forum on architects as developers before an overflow crowd of 300 members. The keynote address was made by Herbert Lembcke, a member of Mr. Portman’s team.

In a recent questionnaire, the A.I.A. asked how many of its members were involved in real estate-related activities. Twenty percent of those responding to the survey indicated that they were active in development, construction management or joint ownership situations.

”There is still some debate within the industry on the subject,” said Ted P. Pappas, president of the A.I.A., who heads his own firm in Jacksonville, Fla. ”And to some extent how common it is depends on size and location of the firm and the personal direction of the principals. It seems less common among large firms in major cities than in other parts of the country. But overall there is more acceptance of the practice.”

The movement by some architects into development might be an indication of increased competition within the field. The A.I.A.’s statistics show that between 1982 and 1987 the number of registered, practicing architects in the country increased from about 61,500 to 74,000.

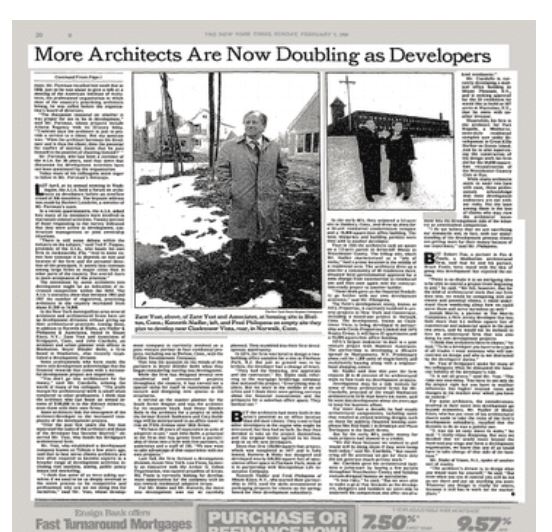

In the New York metropolitan area several architects and architectural firms have set up development divisions without giving up their architectural practices. Among them, in addition to Rotwein & Blake, are Nadler & Philopena & Associates, based in Mount Kisco, N.Y.; Zane Yost and Associates of Bridgeport, Conn., and John Ciardullo, an architect and urban planner with offices in Manhattan. Beyer Blinder Belle, a firm based in Manhattan, also recently established a development division.

Some professionals who have made the move into development acknowledge that the financial rewards that come with a successful development project are important.

”You don’t go into architecture for the money,” said Mr. Ciardullo, echoing the words of many of his collegues. ”The profit margin for architectural work is small when compared to other professions. I think that the architect who can boast an annual income of $100,000 is in the distinct minority, even those with their own firms.”

Some architects link the emergence of the architect/developer to the increased complexity of the development process.

”Over the past few years the line that separated the tasks of the architect and those of the developer has become blurred,” observed Mr. Yost, who heads his Bridgeport architectural firm.

Mr. Yost, who established a development company known as Telesis a few years ago, said that to best serve clients architects are now often required to become experts in a broader range of development activities including cost analysis, zoning, public policy issues and marketing.

”I think that some of us were asking ourselves if we need to be so deeply involved in the entire process to be competitive and professional, why are we not doing this for ourselves,” said Mr. Yost, whose development company is currently involved as a joint venture partner in four residential projects, including one in Shelton, Conn., with the Collins Development Company.

That was the question on the minds of the partners in Beyer Blinder Belle when they began considering moving into development.

While the firm has designed several new residential and commercial projects throughout the country, it has carved out a special niche for itself in restoration architecture and designing new spaces in old structures.

It served as the master planner for the South Street Seaport and was the architect for its museum block. And Beyer Blinder Belle is the architect for a project in which the former Rizzoli Bookstore and Coty Buildings will be incorporated in an office tower to rise on Fifth Avenue near 56th Street.

”We have 20 years of experience in area of adaptive re-use,” said John Belle, a principal in the firm that has grown from a partnership of three into a firm with five partners, 14 associates and a staff of 150. ”We now want to take advantage of that experience with our own projects.”

Last fall, the firm formed a development division, Arcon New York. Lee Fazio, formerly an executive with the Arthur G. Cohen Organization, was named president of Arcon. Ms. Fazio is currently looking for development opportunites for the company with an eye toward residential adaptive re-use.

For Mr. Blake and Mr. Rotwein, the move into development was not so carefully planned. They stumbled into their first development opportunity.

In 1974, the firm was hired to design a two-building office complex for a site in Florham Park, N.J. But just as ground was to be broken, the developer had a change of heart.

”They had the financing, site approvals and the contractor,” Mr. Blake said, referring to the mortgage brokerage company that initiated the project. ”Everything was in place. But we were in the middle of an oil crisis and I think there were getting nervous about the financial commitment and the prospects for a suburban office space. They backed out.”

BUT the architects had more faith in the area’s potential as an office location than did their clients. They tried to find other developers in the region who might be interested, but they had no luck. So they then decided to take on the project themselves, and the original lender agreed to let them step in as the new developers.

Since that first 130,000-square-foot project, which was completed in 1977 and is fully leased, Rotwein & Blake has designed and developed nearly 500,000 square feet of speculative office space in Florham Park, most of it in partnership with Metropolitan Life Insurance Company.

Kenneth Nadler and Fred Philopena of Mount Kisco, N.Y., who started their partnership in 1973, used the skills accumulated in packaging projects for clients as the springboard for their development subsidiary.

In the early 80’s, they acquired a 5.5-acre site in Danbury, Conn., and drew up plans for a 54-unit residential condominium complex and a 10,000-square-foot office building. The land, blueprints and building permits were then sold to another developer.

Then in 1985, the architects took an option on a 7.5-acre parcel in Briarcliff Manor in Westchester County. The hilltop site, which Mr. Nadler characterized as a ”pile of rocks,” had a prime location in the middle of a residential area. The architects drew up a plan for a community of 66 residences there, obtained local governmental approval for a zone change from commercial to residential use and then once again sold the construction-ready project to another builder.

”These deals gave us the financial flexibility go further with our own development activities,” said Mr. Philopena.

The firm’s development entity, known as NPA Properties, is currently involved in several projects in New York and Connecticut, including a mixed-use project in Norwalk, Conn. The development, known as Clocktower Vista, is being developed in partnership with Circle Properties Limited and DPS Realty Group. It will have 61 apartments and a 55,000-square-foot office building.

NPA’s largest endeavor to date is a joint venture project with Hanover Associates. The partnership is developing a 450-acre spread in Montgomery, N.Y. Preliminary plans call for 1,200 units of single-family and multifamily housing along with a neighborhood shopping center.

Mr. Nadler said that this year the firm expects 30 to 40 percent of its architectural work to flow from its development projects.

Development may be a side venture for some of these architectural firms but Mr. Ciardullo, principal of the small Manhattan architectural firm that bears his name, said he went into development about six years ago to keep his business afloat.

For more than a decade, he had steady architectural assignments, including some that resulted in award-winning designs, such as those for publicly financed housing complexes like Red Hook I in Brooklyn and Plaza Borinquen in the South Bronx.

But by the early 80’s, public money for such projects had slowed to a trickle.

”We did these because we wanted to and would still be doing them if they were being built today,” said Mr. Ciardullo. ”But considering all the attention we got for them they did not generate much private work.”

Mr. Ciardullo gave his architectural business a jump-start by buying a few parcels throughout Westchester County and building custom-designed homes on speculation.

”It was risky,” he said. ”But we were able to make a go at that because as the developers, designers and builders we were able to undersell the competition and offer one-of-a-kind residences.”

Mr. Ciardullo is currently developing a medical office building in Mount Pleasant, N.Y., and is seeking approval for the 22 residences he would like to build on 107 acres in Waccabuc, N.Y., that he owns with another investor.

Meanwhile, his firm is the architect for Port Regalle, a Mediterranean-style residential complex now under development in Great Kills Harbor on Staten Island. And he is also supervising the construction of the design work his firm did for the 50,000-square-foot reconstruction of the Westchester Country Club in Rye.

While many architects seem to wear two hats with ease, these professionals acknowledge that their development endeavors are not without risks. Not the least among them is the loss of clients who may view the architects’ movement into the development side of the industry as unwelcomed competition.

”I do not believe that we are sacrificing our standards and, in fact, with our understanding of the development process clients are getting more for their money because of our experience,” said Mr. Philopena.

BUT Robert Fox, a partner in Fox & Fowle, a Manhattan architectural firm, said that he and his partner, Bruce Fowle, have toyed with the idea of going into development but rejected the notion.

”There is no doubt it is an intriguing idea to be able to control a project from beginning to end,” he said. ”We felt, however, that for the kind of architectural work that our firm does now, we would be competing with our clients and potential clients. I could understand them wondering about how we could serve them and serve ourselves as well.”

Joseph Morris, a partner in The Morris Companies, a New Jersey developer that has built more than 8.5 million square feet of commercial and industrial space in the past two years, said he would not be inclined to hire an architectural firm that was also doing its own development projects.

”I think that architects have to choose,” he said. ”To be a developer you have to be a jack of all trades. I want someone who will concentrate on design and who is not distracted by the developers’ duties.”

Mr. Yost of Bridgeport spoke for many of his colleagues when he discussed the financial liability of the developer’s role.

”It is not all gravy,” said Mr. Yost. ”The risks are enormous. You have to not only do the project right but you have to weather influences like higher interest rates and changes in the market over which you have no control.”

For some architects, the considerations involved in their move into development go beyond economics. Mr. Nadler of Mount Kisco, who has put most of his architectural chores aside to take the reins of the firm’s development subsidiary, recalled that the decision to do so was a painful one.

”It was not an easy move to make,” he said. ”I really enjoy designing. But once we decided that we would move beyond the mom-and-pop stage and form a development organization, we knew that one of us would have to take charge of that side of the business.” Mr. Blake of Union, N.J., spoke of another sort of reality. ”The architect’s dream is to design what you would want for yourself,” he said. ”But even when you are in control you still do not go out there and put up anything you want. Whatever you design is really for others, because it still has to work for the marketplace.”