Nightingale Village, a housing development project in Melbourne, Australia, is making a name for itself in the architecture industry for its innovative approach to sustainable housing. What sets Nightingale Village apart is the unique role of architects as developers, taking on not just the design but also the financial and construction aspects of the project.

The project was born out of a desire to provide affordable and environmentally sustainable housing that puts the needs of people and communities first. The developers believe that architects are uniquely positioned to drive the creation of socially and environmentally responsible housing models, given their training in design and attention to detail.

The development comprises seven multi-residential buildings, with a total of 209 apartments, all built with sustainable design features such as solar panels, rainwater harvesting, and green roofs. One of the key features of the development is that the apartments are sold at cost directly to owner-occupiers, cutting out the profit-driven middlemen that drive up housing prices.

Nightingale Village also places a strong emphasis on community spaces and facilities, such as a rooftop garden, shared laundry facilities, and a bike repair station. These spaces are designed to encourage social interaction and reduce the need for individual resources.

The project’s collaborative and innovative approach involves architects, developers, and community members working together to create a socially responsible and sustainable housing model. This is a departure from the traditional top-down approach to development, where developers dictate the design and function of buildings without input from the communities that they will serve.

By taking on the role of developers, architects in Nightingale Village are breaking down the boundaries between disciplines and redefining the traditional role of architects in the building process. They are demonstrating that architects have a crucial role to play in driving socially and environmentally responsible building practices and that they can act as a force for positive change in the housing industry.

The Nightingale Village project has received international recognition for its innovative approach to sustainable housing, and it has inspired similar projects in other cities around the world. The project serves as an excellent example of how architects can use their skills and expertise to create positive social and environmental outcomes, not just in the built environment but also in society as a whole.

In March 2023, Alexis Kalagas posted the article “Nightingale Village” at ArchitectureAU.com. See the full article at ArchitectureAU.com.

]]>To learn more about Jason, go to his:

Website: https://boyervertical.com/#

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/jasondboyer/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/boyervertic…

]]>To see more about Drew, visit his website at: https://langarchitecture.com/

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/drew-lang…

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/langarchite…

]]>

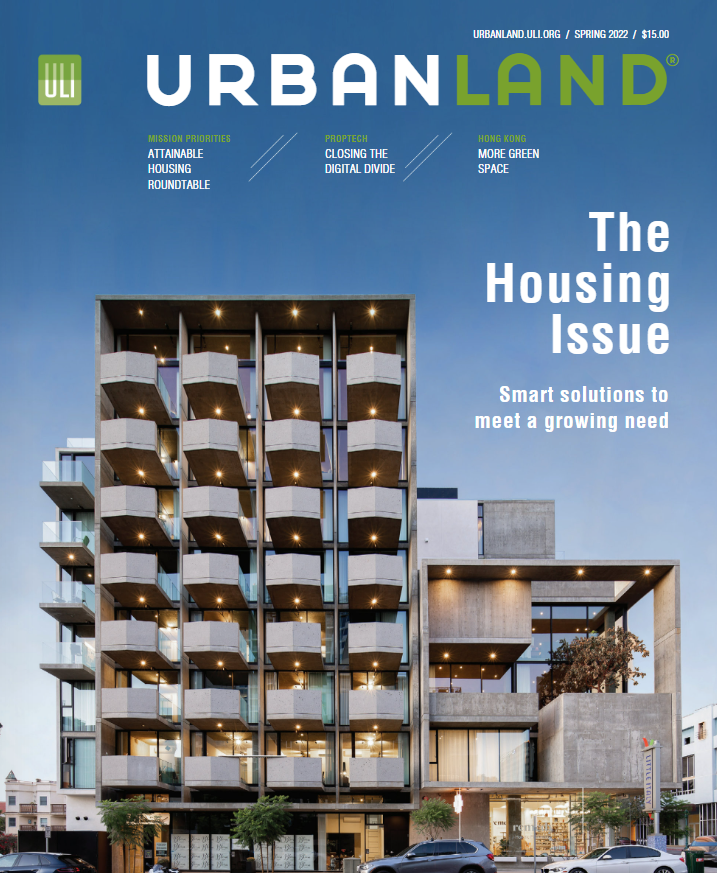

Urban Land’s Spring 2022 cover depicts a groundbreaking micro-housing project in the heart of downtown at 320 West Cedar Street in San Diego’s Little Italy. Designed, developed, owned, and managed by local architect Jonathan Segal, the 42-unit structure features 5 low-income apartments, two commercial retail spaces on the ground floor, and a distinctly separate single-family townhouse designed by Matthew, his son, that looks like a cube on the corner. And all on a 5,000-square-foot postage stamp size lot.

Like all of Segal’s projects—he now owns and rents 160 units in 5 buildings in and around San Diego—The Continental began as an experiment. This time, the architect cum developer (cum general contractor cum owner cum property manager) wanted to provide housing for people who worked downtown who didn’t have cars. The result: micro workforce houses at a price point of 65 percent of the average market rent.

The architect’s penchant for experimentation has earned him dozens of top local, state, and national accolades from groups like the American Institute of Architects for residential and urban design. In mid-2020, he was awarded Master Architect for the City of San Diego, the youngest architect at then 59 to receive the honor in a field with 5 living recipients whose average age is 91. He was also awarded California State AIA’s 2021 Maybeck Award for career design work.

Urban Land spoke with Segal about The Continental and his innovative approach to projects that push the envelope of possibilities.

What makes your firm stand out?

Segal: We don’t have any clients. We do our own work. We develop our own work. Each project that we do is sort of an experiment of what we think is pertinent to the time or germane to what is at issue at the time.

Every time we do something, it’s rooted in architecture—it’s not from development. It’s not numbers. It’s not beans. It’s not density. It is: What is right and what are we trying to investigate as an urban architectural experiment?

The Continental was created because the housing downtown was expensive and we needed to create some kind of workforce housing so people who didn’t have cars and could not pay the extra freight for a parking space could have a unit and we wouldn’t have to build an underground parking garage, which would save us money. And that was the genesis of what we wanted to do. We wanted to provide urban workforce housing.

How was this project informed by the California housing crisis and what are the chief obstacles to getting this type of affordable project done?

Segal: This was our answer to the current housing affordability crisis. It’s the law of economics; it’s supply and demand. If there’s big demand, and little supply, things get expensive. There’s a whole bunch of supply and no demand, things get real cheap.

I don’t think that the cities are allowing us to build quickly enough and easily enough and efficiently enough. They’re still getting in our way. They’re just not letting the gates open. It’s amazing to try and get something processed still. The fees are outrageous. I wish that we could work closely with cities to vet issues that would make it more efficient to process a building permit—clearly, that would be the key to the supply issue.

What inspired the design of The Continental?

Segal: We wanted to develop a project with no parking. Its façade of balconies is patterned after a Lincoln Continental car grill. So if you look at the pattern of the late ‘50s Lincoln Continentals, the grills in front of the radiators have a pattern and that was the genesis of a pattern created with the decks. Everything is car-related for me. I collect ‘50s Italian cars and ‘50s and ‘60s American cars. There is an incredible design vocabulary in these cars that I build from.

When did it come online and who is your target renter?

Segal: It was two years ago in December 2019. What we’re trying to do is we’re trying to make it for the people who actually work in Little Italy to live in Little Italy. So if you’re a bartender and you walk three blocks to work, you don’t need to pay $400 for a car payment, another $200 for license and insurance, which is $700 a month. You can apply that to your lifestyle and/or your unit. And if I can make your unit $700 or $800 less expensive a month because it doesn’t have a parking space attached to it, there’s more savings. So it’s just all-around lifestyle savings for people that can’t afford expensive downtown. The rents for 37 of the units, which are 350 square feet or less, are $1,595 to $1,995 with affordable ones at about $900 a month.

Initially, when it came online, this was an experiment. This was sketchy, risky. They didn’t immediately rent up. We had to get our market of the people without the cars in and that was a tight, small market at the time; it’s grown significantly now.

Social interaction is important in urban architecture, so we created an outdoor space at the top of the building, facing the ocean, facing the San Diego Bay. It then has its washer and dryer room connected to it so you can go up and be social, do your laundry, and then socialize with people in the building and have a fabulous view you couldn’t afford because you can only afford the unit on the second floor. So very democratic the way it enables all people to enjoy the best parts.

It is a very good product type to develop provided you don’t have to provide parking for it. And we’re seeing that all over San Diego now; we’re seeing a lot of developments. We do by example, and they copy. They’re everywhere now.

What makes your micro-housing design unique?

Segal: Besides bringing a substantial reduction in parking, we brought large individual private outdoor living spaces to indoor living. That is extremely important in a small rental and also to capture the incredible San Diego weather. And we brought an efficient layout of living space. It’s 350 square feet or less and we have a big, huge sheet of glass at the end of it so the space feels like it’s larger whereas typical developers put a four-by-four or five-by-five window at the end, this is a full-blown, huge commercial-grade window system and a nice patio that’s eight by eight.

It’s only been two years but what kind of turnover are you seeing?

Segal: Our tenants are staying. We were wondering about the units being so small if the turnover would be more than the larger complexes with the larger units and the answer is no, it’s basically the same. It’s crazy. It’s also important to remember Matthew developed a single-family residence and placed it over his Remedy Pharmacy. This living over the store row house is another typological pattern that needs to be understood in urban San Diego regardless of the unit type. We try to be a little less expensive, so we have less turnover because turnover is costly.

What are the sustainable elements of The Continental?

Segal: No parking, no cars, more transit use, more walking, more healthy lifestyle. We have nominal parking, 9 parking spaces for 40 units. And if you’re walking and your neighbor’s not because your neighbor has a car and you’re walking a mile or two a day, you’re going to be healthier. Your being healthier is going to help with your longevity. It’s going to help the medical system—it’s on and on and on. Sustainability isn’t just using bamboo floors. You know, it’s an idea, not necessarily a product. People get that confused. High density is sustainable. Urban suburban sprawl is not. I don’t care if you’re making it out of recycled building paper—your whole house—it doesn’t matter. You’re burning fossil fuels to get from here to there.

I have the most efficient mechanical electrical units that you can buy. The building is made out of concrete so the maintenance on the building is almost nothing. I’m not painting it. I’m not staining it. I’m not doing any redos. The storefront is an expensive product that lasts longer than cheap builder/developer windows. Operable windows for cross ventilation so you don’t have to run an air conditioning system if you don’t want to. We have complete solar, as much as we can fit on the roof to offset the building expenses. We don’t have batteries.

How much does the solar offset the building expenses?

Segal: It covers about 80 replace of the building itself, not the units. We just don’t have enough physical real estate area up there. We would have put more but there’s the physical square footage of the buildable solar area limited us, which is pretty typical for urban housing. You’re limited by your roof.

Do the smaller units make the math work but also mean more management?

Segal: Yes, smaller units allow us to charge less rent. And yes, you’re going to have a couple more units of turnover just by the mere fact that a percentage on a higher number is going to equate to more move-outs. So it is more labor-intensive or management intensive to manage smaller units. Without a doubt, there’s no question.

Does it have any green certifications such as LEED?

Segal: We don’t believe in that. We’d rather spend the money on the building making it green rather than spending ten grand on some certification expert to certify that we’ve done what we’re supposed to do.

This is also a mixed-use project…

Segal: We have two retail spaces. Matthew actually lives above the store like my wife and I have done since 1989. He has a holistic pharmacy called Remedy with his wife and they’re raising their first child there, Oliver.

You mentioned another rowhouse development where you created fee simple ownership over 30 years ago…

Segal: I was trying to get a fee homeownership to downtown and I cut a 15,000 square foot property into 15-foot-wide lots. And then I created something I call ‘convertible housing.’ I’m going to give you the opportunity to have sort of an extra flex space that you can either have your home office in or you could rent out as a separate unit. And if you bought one of the homes that also came with a granny flat, there would be an additional commercial space under your row house. Physically you had your business below and your home above, no commute required. And you can also rent out those spaces for income. So if you get the down payment from your parents, effectively you can live out of it for free. And that was my first foray into developing fee simple living at home and working at home. That was ‘98 and we called the project Kettner Row.

How do you replicate the best of The Continental in other projects?

Segal: We are now starting to incorporate micro-units as part of our product types. So the building next door, the high-rise—25 replace of the units are 350 square feet.

What’s your next project?

Segal: It’s a high-rise that we’re currently getting ready to build next door to The Continental. And because we own contiguous properties next to each other, we are able to for a maximum building height basement of the Continental property and this basement allows us to have a glass wall on the property lines that we wouldn’t be able to otherwise have.

We bought a 50-by-100-foot lot and we developed a 73-unit, 23-story tower there on it. We have an automated parking system that goes with that, which is kind of a first of its kind in San Diego. Typically, a downtown building has got maybe six levels below grade of parking. So you drive into a hole and you spiral down six floors to a space that has bad air and maybe encounter unsavory people without any security.

Our system basically takes half the area of a conventional garage. Your car rolls into this little vestibule parking, and you get out and the machine comes and takes it away. And then it puts it on an elevator, and it stacks it on the eight-story parking area against the building where we don’t have windows. And we’re doing it on a non-buildable lot—50 by 100—in downtown San Diego, so there’s an experiment. There’s a demonstration. No one’s done it. So there’s an opportunity.

Where does the project stand now?

Segal: We hope to break ground in September. We’re in the final process of getting our entitlements and our building permits. The cost of the building is around $31 million construction costs for 73 apartments. We’re giving away eight units to the city of San Diego free of charge for affordable housing. So the city doesn’t have to put a dime out and they’re getting these subsidized units that are about 35 percent on the dollar for rent so if it’s a $3,000 unit, it’s $1,000. If it’s a $4,000 unit, it’s $1,300. It creates a pretty good deal for everybody.

See more about Jonathan Segal {here}.

]]>Also, check out the Context & Clarity show that I took part in earlier in 2021 {here}.

In the Irish Channel area of New Orleans, 12 new homes cluster on a former warehouse site. Angular, covered in corrugated metal, and painted white, the homes are jigsawed in a way that makes room for patios, courtyards, and parking. Inside, they have polished-concrete and wood floors, energy-efficient fixtures, and soaring ceilings. But what’s most special about these houses isn’t just their modern design: it’s the creativity that went into building on a site where the law, at first glance, only permitted three single-family houses.

In a bid for density, sustainability, and affordability, architect Jonathan Tate conducted legal alchemy and found ways to subdivide the land and use multifamily zoning ordinances to construct 10 fully detached homes and a duplex.

“I tried to push the land as far as I could,” Tate says.

Tate purchased the land and developed the project himself—an unusual scenario for an architect. Using design to maneuver complicated zoning and ownership laws, he was able to build an experimental infill project that adds high-quality, much-needed housing to New Orleans. Though Tate considers his firm to be a traditional architectural practice, this isn’t the first time he’s served as his own developer. In 2016, he designed and built the first of his Starter Homes—compact single-family houses built on inexpensive and oddly shaped infill lots—which helped establish his reputation as an experimental and forward-thinking designer.

“If anything, our idea of developing was just to implement an idea. It was also a form of advocacy for the discipline so architects can engage in projects and possibilities that precede [the traditional design process],” Tate says.

A closer relationship between architects and developers—and sometimes a blending of the two—is unlocking more creative construction and problem-solving in the built world.

The design-development duel

Buildings can be constructed by a number of different entities: architects, engineers, developers, contractors. One scenario—common for custom homes—is that architects design a building, then bid it out to a contractor who subcontracts to tradespeople. Sometimes architecture firms develop their own projects and call themselves “design-build” firms.

Architects design buildings, so the assumption goes that all buildings are designed by architects. That’s not always the case, especially when it comes to multifamily developments, tract housing, high-rises, and master plans. Developers, along with engineers, come up with the program of a structure, using guidelines from zoning and building codes to shape the size of rooms, number of floors, footprint, and setbacks. Sometimes a developer requests proposals from many architects and chooses one. Sometimes an architect is brought in in the middle stages of a project to style the building’s envelope or to address a particularly sticky problem. They’re not always involved after something breaks ground. And the builders aren’t involved in the design process, which has led to some high-profile blunders.

In Brooklyn, SHoP Architects, the developer Forest City, and prefab builder Skanska worked on a residential high-rise, which was the world’s tallest modular building when it was proposed in 2011. The 32-story building was plagued with stop work orders, delays, leaks, and lawsuits. The builder sued the developer, alleging a bad design, and the developer sued the builder over faulty construction.

Meanwhile, the lack of design in development—particularly in multifamily residential projects—has led to a proliferation of the same bland and boring buildings in cities across the country.

Developers often perceive architects’ contributions as expensive, unnecessary, and time consuming. Architects often worry that developers will value-engineer the “design” out of a project or focus too much on practicalities. “There’s an antagonistic relationship because the sense is [architects] don’t share the same values and goals as other disciplines involved,” Jonathan Tate says. “Builders don’t care what it looks like, developers are looking at the bottom line… it’s a financial transaction versus a design and experience. And that’s a really poor way to see the world.”

Michael Samuelian—an architect who has spent much of his career working for developers and who led the Hudson Yards megaproject and post-9/11 reconstruction of lower Manhattan—believes architects and developers need to learn from each other. Recently appointed to lead the Trust for Governors Island, Samuelian is taking a design-lead approach to preserving and redeveloping the historic site in New York’s harbor. And this fall, he is teaching an advanced design studio on developing Governors Island at the Yale School of Architecture.

“Each profession shares optimism,” Samuelian says. “Architects believe design can solve everything. Developers believe the world will be better with their building in it. … Architects should be more sensitive that they exist in a project for a very limited time: A project starts well before they’re involved and lasts well after. Developers can benefit from valuing design, but knowing it’s not equal: Just because a building is well designed doesn’t mean it’s expensive, and, vice versa, just because it’s expensive doesn’t mean it’s well designed.”

The dichotomy of architecture and development exists partly because of how these professions are traditionally taught.

“The culture of architecture is that of a high art and being careful not to get too sullied and dirty with reality,” says Chris Calott, an architect, developer, and chair of Real Estate Development and Design master’s program at the UC Berkeley College of Environmental Design. “Particularly in architecture school, it’s a mindset and tradition that’s hard-fought. I always say you can ignore [the realities of development] but you do so at your own peril.”

UC Berkeley’s program welcomed its first students this fall. It teaches people with an architecture background how to better understand development, and encourages design appreciation in people approaching development from a real estate perspective. The inaugural class of 16 students is composed of designers, house flippers, and people working in affordable housing and policy.

A handful of architecture schools offer graduate degrees in real estate development, which is typically the purview of business schools. Columbia University’s GSAPP launched its master’s degree program in 1985 and has graduated 2,185 students since then. Woodbury University also has a master’s program, and so does Pratt University. MIT offers an interdisciplinary course of study. Before establishing UC Berkeley’s program, Calott led Tulane University’s master’s program in sustainable real estate development. Teaching design and development together fast-tracks the appreciation and expertise each side needs to really understand the other, he says.

“The best development companies are doing the best projects by working with very good architects and solving problems together,” Calott says.

The business case for design-led development

If architects and developers collaborate closely, both sides see advantages. But architects who have embraced development work say they’ve experienced windfalls creatively and businesswise.

When Lightstone, a developer of residential, hospitality, and commercial projects, embarked on 40 East End Avenue, a forthcoming 29-unit, 20-story boutique condominium on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, it integrated design, development, and marketing from the beginning, betting that the approach would assure the project’s success in a fluctuating market.

Lightstone enlisted Deborah Berke Partners to design the building and Corcoran to create the marketing strategy. The three worked together to make sure the building would be unique, desirable, and, ultimately, financially successful. They conducted detailed demographic research about the target market for the building—which informed structural detailing and interiors—and examined New York City zoning code for opportunities to increase buildable space and therefore profitability.

The team ended up selecting energy-efficient mechanical systems, using thermally resistant walls, adhering to “quality housing” rules like maintaining neighborhood character architecturally, and including amenities like landscaping. The end result? A residential building that’s stylistically distinctive and structurally ambitious.

The building—with its a masonry facade, punched windows, terra-cotta detailing—references historic structures found around the neighborhood. Inside, marble floors set in a black-and-white herringbone pattern and a sweeping staircase greet residents and visitors. The interior palette of natural materials and richly textured textiles appeals to the senses. The architects also added extra storage and a coworking space to appeal to prospective buyers.

The financial boons of becoming a developer aren’t just in the rates a building fetches. To Jonathan Segal, becoming an architect-developer made sense creatively, as well. “We can do what we want and answer to no one,” he says. “I feel bad for architects that get pummeled and hammered and work cheaply and become bag boys when they could do this.”

In the more typical business structure, in which a separate owner, architect, and contractor work on each project, creative differences or rising costs can quickly sour relationships. When things go wrong, it’s the architect who gets blamed.

“The triangle is problematic from the start,” Segal says. “If you remove two of the points and I’m the architect, owner, and contractor, when I do mess up I’m able to fix the issue on my own. If something doesn’t turn out how I wanted, I can fix it.”

Trained as an architect, Segal worked for two firms before launching his own. For his first solo project, he tried shopping a row-house development, which he designed for his thesis, around to different developers until one of them encouraged him to develop it himself. “He told me: ‘You’re an idiot. Don’t be an architect; develop it yourself.’”

Segal found some inexpensive land and constructed his row houses. The profit he earned the first year exceeded his expectations, and he continued on his trajectory as a developer who designs his own projects. He specializes in mixed-use residential and commercial infill projects.

Because his firm is essentially the sole point of contact for a project, his subcontractors receive swift responses to questions and issues that arise on projects. He has strong working relationships with them as a result, which leads to faster construction and more leverage in cost negotiations for future projects. There are also legal benefits, Segal points out, that ultimately save time, money, and creative energy. He says he’s only been sued three times in the past three decades of business, which he claims is a low rate for the construction industry.

“We have control and we’ve utilized it to keep out of trouble,” Segal says.

Since launching his company in 1988, Segal constructed 245 buildings in San Diego and concentrated much of his work around the city’s Little Italy area. His projects include micro-unit apartments, luxury lofts, adaptive reuse, and more. His business structure has allowed him to build a cohesive, intentional body of work.

“My goals are to influence and change urban San Diego,” he says. “It’s not about making money or creating an object; it’s about creating change and a legacy. If you made a shit ton of money on bad things, who cares. But if you have a legacy on improving something, that’s great. It’s important that happens.”

Creative problem-solving in a world where it’s harder to build

For architects to create measurable change, scale is needed, which is where either becoming a developer or partnering with a like-minded developer becomes essential.

The building industry is facing a number of challenges, including labor shortages, a volatile materials market, and escalating construction costs. Meanwhile, bureaucracy has slowed new development and land is becoming prohibitively expensive in areas where new structures are needed most. Macro issues, like climate change, are also affecting the characteristics of buildings and neighborhoods. Developers and architects have to get more creative with how—and why—they build.

Allison Arieff—an architecture critic, editorial director of the urbanism think tank SPUR, and lecturer at the UC Berkeley College of Environmental Design—sees a real mismatch between the buildings being built and what people need from their buildings, particularly as it relates to housing. Most housing in the U.S. is designed and built by developers, and that’s led to generic homes and neighborhoods tailored for investment rather than livability.

“Ultimately, there are a lot of deeply ingrained concepts of what homeowners want that have a lot more with the building industry and realtors than the reality [of what homeowners desire],” Arieff says. “You’re not thinking about what’s useful to the person in it. In a resale-obsessed market, they build to perceived future value versus what meets someone’s needs.”

She advocates for addressing sustainability head-on in housing, designing homes for community, and making spaces that will work for different genders and age groups instead of an archetypical buyer. Architects’ input on residential developments could go a long way toward improving the quality of life.

“If you look out at developments across the country, there’s homogeneity and repetition and lack of appreciation for context and planning for creating neighborhoods. It’s pretty stark,” Arieff says. “I think we’re suffering from the results of not doing that… For example, a development might have a shopping center next to it, but you can’t walk to it. It’s tiny little details like that that are super frustrating and don’t have to be that way.”

David Baker Architects, which specializes in multifamily residential projects, leverages strong relationships with like-minded developers to construct affordable and environmentally minded housing, including collaborations with Bridge Housing, a mission-driven nonprofit developer, and Holliday Development, a for-profit company known for mixed-use projects and rehabbing industrial buildings into live-work spaces. The firm has become nationally recognized for its civic-minded body of work, much of it in San Francisco, amid an unprecedented local housing shortage and stringent construction regulations. The architecture firm usually sticks with a project through construction to make sure the most important elements endure the inevitable value engineering.

To Daniel Simons, a principal at the firm, having that strong working relationship with development partners and a willingness to see the bigger picture helps ensure a project will be successful, even if it has to be redesigned due to cost.

“Projects get messed up for lots of reasons—it’s like death by 1,000 cuts,” Simons says. “Sometimes it’s because of a big decision at the beginning, but a lot of times it’s little things that get lost on the way, from a bad choice or a lack of vision. It’s really important to stay involved and keep involved at all stages.

“As architects, we have the opportunity—and I think the responsibility—to always be advocating for the things we think are right for a project—like sustainability, livability, thermal comfort or whatever it is,” Simons says. “It’s easy for developers with lots of experience to say ‘We don’t do that,’ and for architects to say, ‘Okay, we don’t do that here’ instead of saying, ‘Things change.’”

David Baker Architects learned how to be a good development partner through years of experience and trial and error. Jonathan Tate was able to build his infill projects because his curiosity about zoning and insurance regulations led him to building opportunities most architects and developers would overlook. At Hudson Yards, Michael Samuelian created a high-rise neighborhood on top of active train tracks by taking a design-led angle to development. The marriage of design and development is creating some of the most exciting built work today.

“Real estate development needs to take design seriously because it can add so much value, solve problems, and make better urbanism,” Calott says. “[Architects] naturally think about cities and development. We are inherently working in the real estate industry already. Why not be mindful and be better?”

]]>Monograph has a series of great webinars on professional practice that you should check out if you’re interested in pushing the boundaries of professional practice. See more of their webinars at monograph.com.

“Unfortunately most developers are focused on the bottom line. The unfortunate thing about architects is that they care deeply about the design but rarely have the opportunity to exercise that. When you’re under one roof, you get a developer who is more focused and more thoughtful on the design.” – Alexandra Militano

]]>