Architect & Developer: Self Initiating Your Work

My name is James Petty. I am here with Alex Barrett, Jared Della Valle, and Peter Guthrie of Barrett Design, Alloy, and DDG respectively. I work on a website called Architect & Developer. If you guys are interested in this stuff, I am always posting new things on the website and on Instagram @architectanddeveloper.

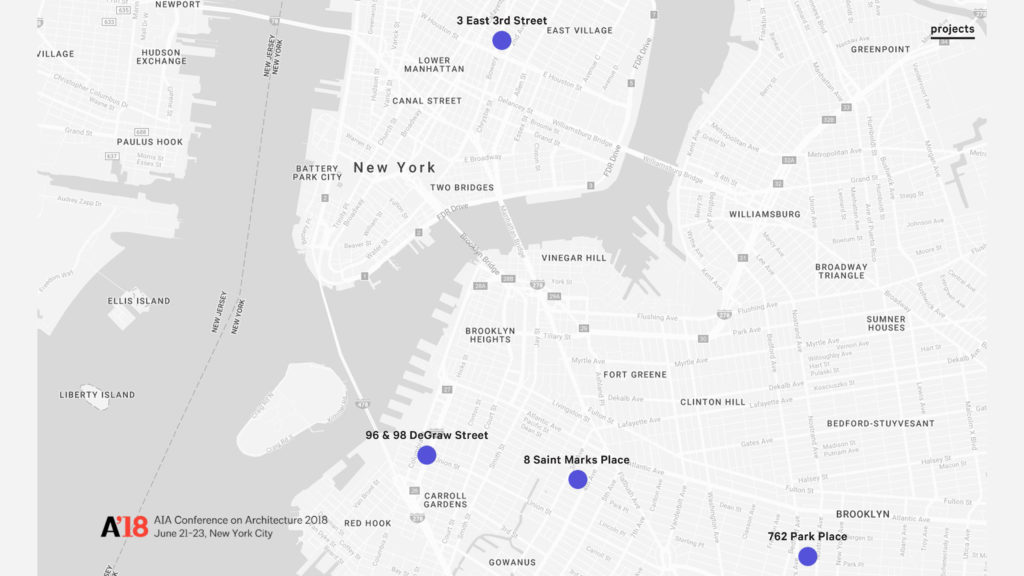

For the conference, I have put together an interactive map. Go to bit.ly/archdev from your phone browser and this will load into your Google Maps app. This will show you a lot of the projects around New York City that have been developed by architects. There are actually a lot. If you are walking down the High Line, you would be really surprised to look left and right and see projects that have been developed by these guys as well as others. On that note, let’s start with Mr. Alex Barrett.

Alex Barrett – Barrett Design

It’s a privilege to be here and especially to share the stage with Jared and Peter. Barrett Design has been around for 13 years. I started it with the premise that combining architecture and real estate development will improve both. It is our belief that designer-led real estate development is more thoughtful, more meaningful, and ultimately creates more value. At the same time, it is our belief that architects who sit in the owner’s seat are more effective, more disciplined as designers, and ultimately more profitable if all goes well. At this point, my firm is a team of seven. We have six architects and an office manager. We approach each of our projects as designers first. We seek to create the best buildings that we can within the many constraints that we are faced with, but also guided by a core set of values.

To date, we have finished eleven speculative development projects. Mostly in Brooklyn, but we just started one in Manhattan. We have four projects under construction at the moment ranging to as few as two-units to as many as twenty-three units.

James asked us to speak a little bit about how we structure our projects. Our project structure, at least from a capital standpoint has been pretty consistent over the past 13 years. We identify a project that has some sort of untapped and uncreative value that we can create through design. We raise equity from investors. At this point, all of our equity is raised from individual investors. We haven’t used institutional equity which I believe is a departure from my fellow panelists. We raise debt from construction lenders as well, and I think James will talk a little more about that kind of typical capital stack. The process of finding projects is the hardest thing for us. I wish I had a good answer for how we do it, but it’s really by hook and by crook. Brokers are involved in a lot of transactions.

Most of our projects have been condominiums, but this is a departure for us. This is two single-family townhomes in the Columbia waterfront district in Brooklyn. Our first project in Manhattan is about a third of the way through construction right now. It’s just off the intersection of East Third Street and Bowery. Not far from here [The New School]. It will be a six-unit condominium at about 20,000 square feet with retail space on the ground floor.

Jared Della Valle – Alloy

Good morning everyone. I’m Jared Della Valle, the CEO of Alloy. Alloy is a real estate development company. Twelve years ago, I had to say that I quit architecture. It required a little bit of therapy to go there after growing up and going to architecture school and always imagining that was the outcome. I felt like when I said I was an architect doing development, people didn’t understand what that meant. They thought it was the lite version. When I said I was a developer, people understood it, but people thought that I was evil and that I had genuinely quit and didn’t care. So it was a confusing dilemma that we face. An identity crisis is what we call it. We’re sort of like a platypus.

Alloy is a real estate development company. It was funny watching Alex’s slides. I feel like each of us could give each other’s lecture, certainly the beginning part. We distort the use of the word “value” in our practice. As architects, we grow up. We all feel the social contract, the moral obligations, the production of great work in our city, and we believe that architects as developers can make better choices. We can distort the use of the word “value.” In our practice, value is not about economics, it is about great architecture first.Our company is very strange. We are actually six companies. I shutter to show our corporate tree. I thought about it for a minute. I thought that this is the AIA, and that they may not like it. We are a development company, that is the holding company. We have a design, LLP. We have a real estate brokerage company. We have a construction company. We have a management company. And we have a community development company. We kind of do whatever it takes. We joke, “OK, Alloy TV/VCR Repair.” Typically we find that we can solve the problems better than the industry can.

So this came early on in my career where I recognized that developers need us early on in the process and they need us until the end. But we extract very little value from the time commitment and the from the value creation over time. Perhaps acquisition and project conceptualization, the development of program, might not come from the architect. Sometimes it does. Ultimately, the management doesn’t. But we still get the phone calls, don’t we? In the end when something goes wrong and it’s two years later. And we answer. We get nothing for it.

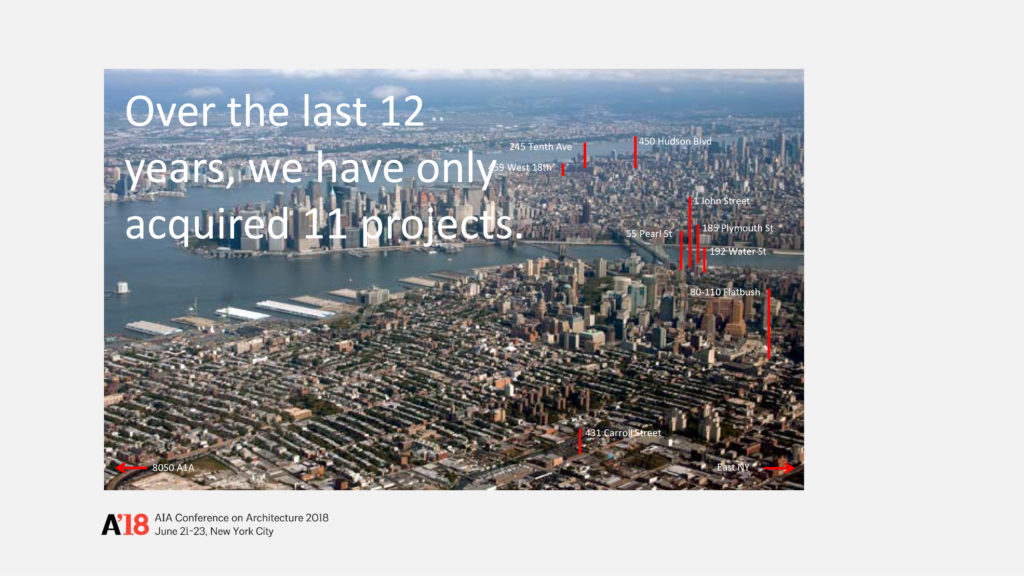

So over the last twelve years, we too have only acquired eleven projects. You’re starting to see a theme here. We only work on one thing at a time. We have no clients. We work for no one other than ourselves. We provide no services other than to ourselves. It keeps you focused on what it is that we are doing and how to manage time and prioritize the development process. Right now only one project is active. As of the other day, we acquired another one. It is sort of rare. We think about our work a little bit differently. Our office certainly functions differently. I will get into that a little bit.

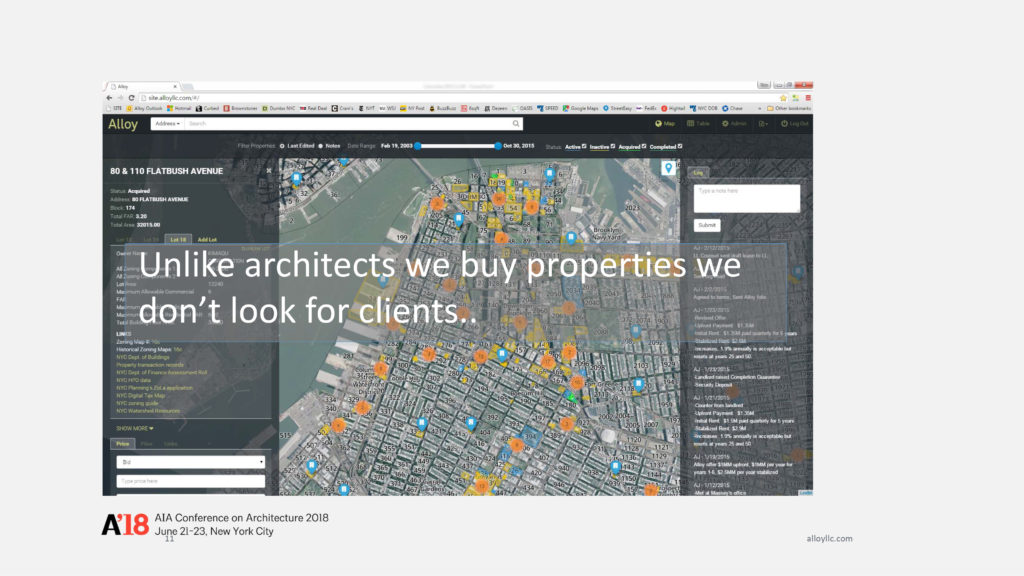

Unlike architects, we buy properties. We don’t go looking for clients. There is a big difference. We invest the process of how we go about acquisition differently. Here you are seeing a piece of software that we developed. It is a map-based communication tool that we use in our office to identify what we have looked at in the past, associate news affiliated with different properties, connect to all of the zoning data and property transaction records that exist in the city. Even more than that, it is sort of like a dashboard in our office that helps us identify who we have spoken to in the past and enables us to see information in a different way.

This idea came to me in graduate school. This was my graduate school thesis. I had this idea for an architect-led development company that was also a contractor. I was recognizing that this is a broken industry. This is my timeline of how this went for me. I will get into a little bit about how our office works as well.

So it was my graduate school thesis in ‘95. When I graduated from school, I graduated with both a Master of Architecture and a Master of Construction Management. I kind of didn’t want to be told that I couldn’t do something, but rather that I could learn how to actually build here in the city. So I worked at a construction company for five years. While I was at the construction company, we won a design competition with my former roommate from graduate school for a federal plaza project for the GSA in San Francisco. In ‘98, we had taken on our first job. I was twenty-four years old and I became incredibly frustrated with the process of how we go about getting clients so I started to pursue development and tried to acquire sites as a way to build work for the practice.

Our first project as a developer, we won an RFP [Request for Proposal] in the City of New York for affordable housing. I then helped someone else acquire property. Then acquired my own property at 459 West 18th Street. In 2011, we dissolved the architecture practice formally, and I had already started Alloy already in 2006. So in 2016, Alloy had turned ten, and now we are working on a project that is a little over a million square feet. So we’ve been partners since 2006. We have worked on twelve projects. We have invested around $110 million of our own capital. We have managed about $430 million of equity. We borrow a lot of money. That is one of the big differences between architects and developers. It’s hard to borrow money as an architect. We are now approaching 2 million square feet of development at over 1100 units.

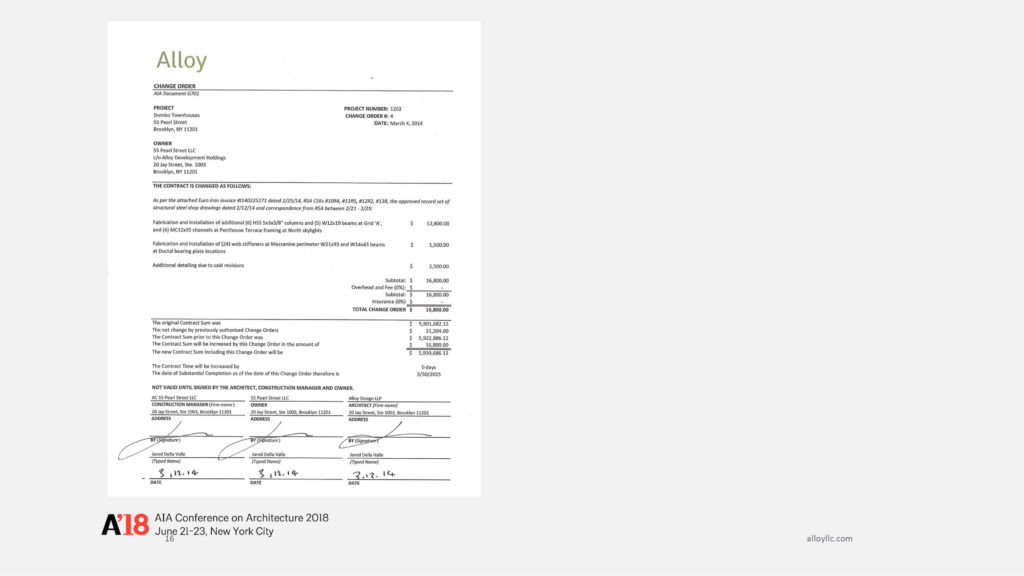

One of the big differences between our practice and an architecture practice is that we take a lot of risk. This is a note by business partners that one of my business partners left me with one of my legal bills that says, “holy shit pies” on it. We are spending about $120,000 per month on legal fees to manage the opportunities and to rely on different consultants on doing the things that we do. We things about things a little bit differently. This is a change order signed by me as the owner, signed by me as the architect, and signed by me as the contractor. We run our practice a little bit differently. Somehow our bank requires this formalization of the process that our industry has already defined. It’s the way we go about things. We kind of play by the rules, but don’t.

There are four partners. We have eleven employees and two admin, which makes 17 in total. We think of ourselves as more like 34 people though. Everyone in our office is like a swiss army knife. We are working on one project at once. You might be involved in marketing one day, you might be involved in construction another day, you might be involved in acquisition another day. There is only one person in our office that has real estate training. We are all architects. We have this incredible capacity and the economics are not rocket science. How much does something cost? How much is it worth at the end? We have run our practice that way.

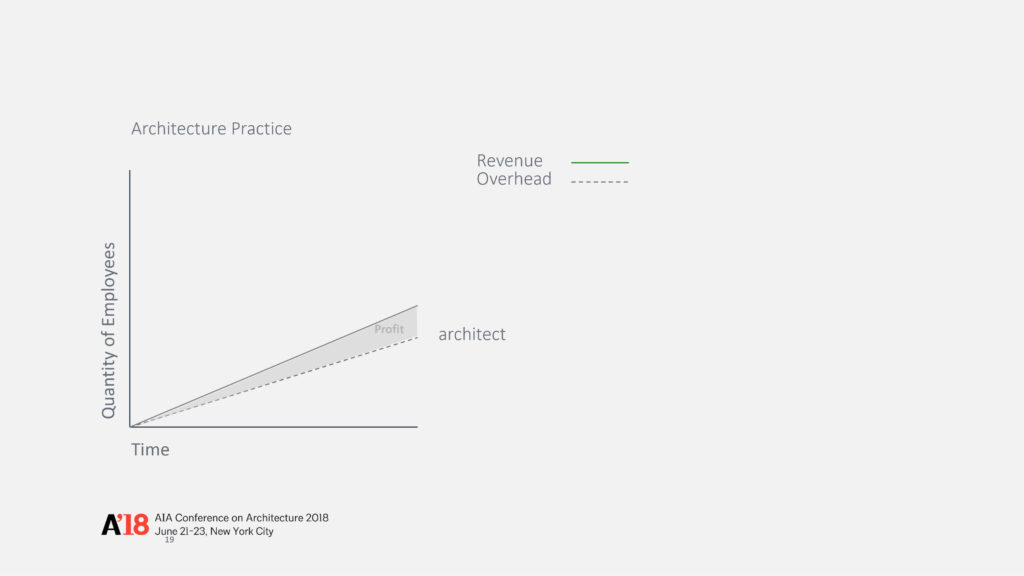

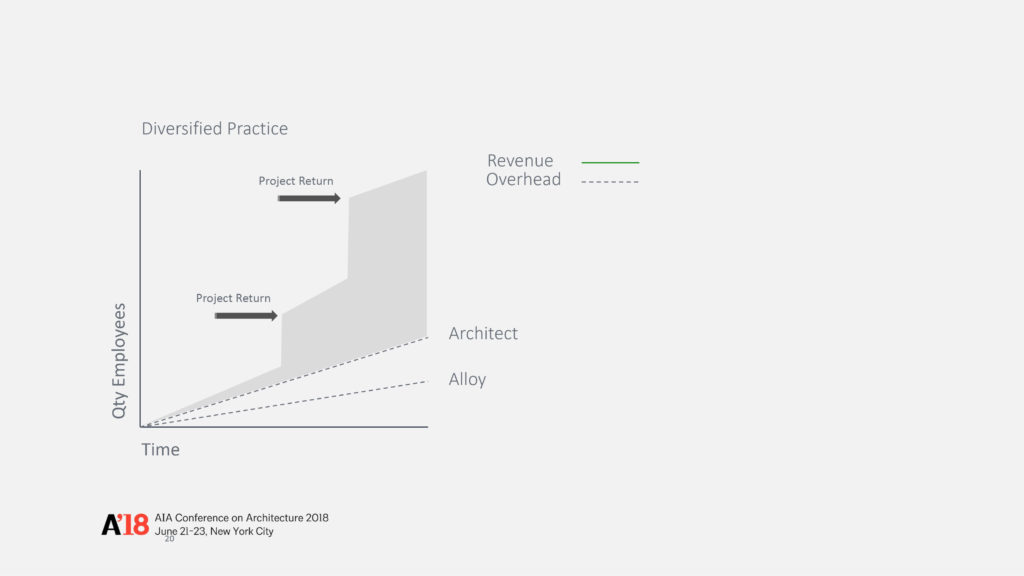

Eight of our employees are licensed architects. It’s been like a gateway drug for people. Once you are here, you can’t imagine unscrambling a scrambled egg and just providing service. So the typical architecture practice works off a pyramid right? You have employees, and you make money off of those employees. The more employees you have, the more theoretical revenue you can make. With a development company, we have that too right? We have something that we call “Money Day” in the office. My partner sends me a bill, and I pay it. We do that for architecture services, for development services, and for brokerage services. But more than that, we actually get the value out of the real estate. So we have these moments where at the end of the project, there is meaningful value there that we have created and achieved that’s different right? We have a project return.

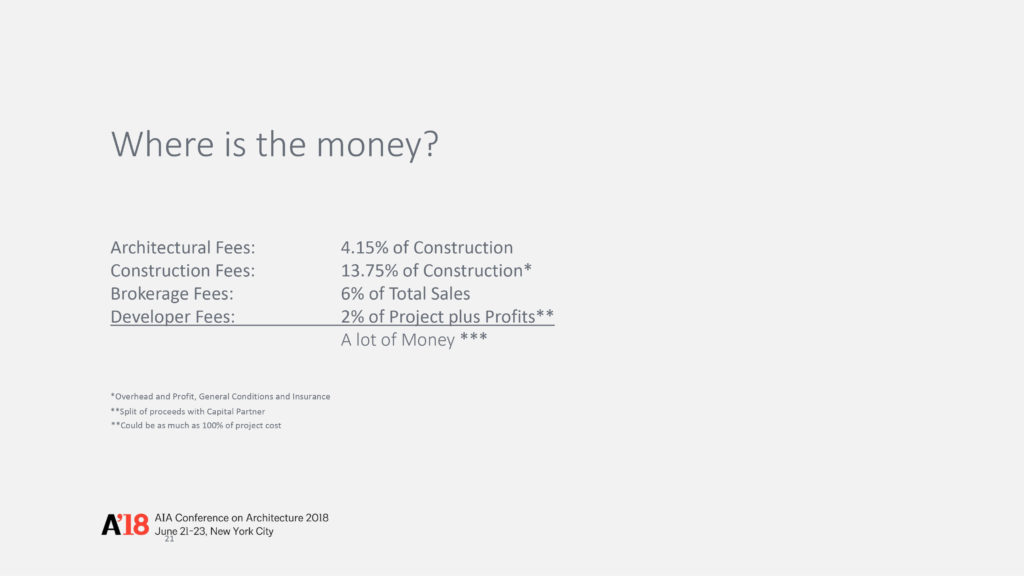

So how does it go for us? This is a typical project that we are working on now. A hundred million dollars is the type of project size that we like. So this is a general sense of how this works for someone like us. We pay ourselves architecture fees, construction fees (including general conditions and other things for our own construction company), brokerage fees (for doing the sales). Nobody is better at sales than an architect, I promise you. There is no broker who can outsell one of us. And developer fees. We pay ourselves developer fees every month. We get a developer draw. And keep in mind, that I am billing the same employees for the same tasks multiple times at the same time. At the same time, we get project profits. On one hand, we are taking all of this risk and it seems a little bit crazy, but if you add all of those numbers up, remarkably, I have created a hedge for risk. The market can go down quite a bit, but if I only make my fees, we have still done well, right? So I have protected myself market-wise by taking on all of these roles and ironically taking risk.

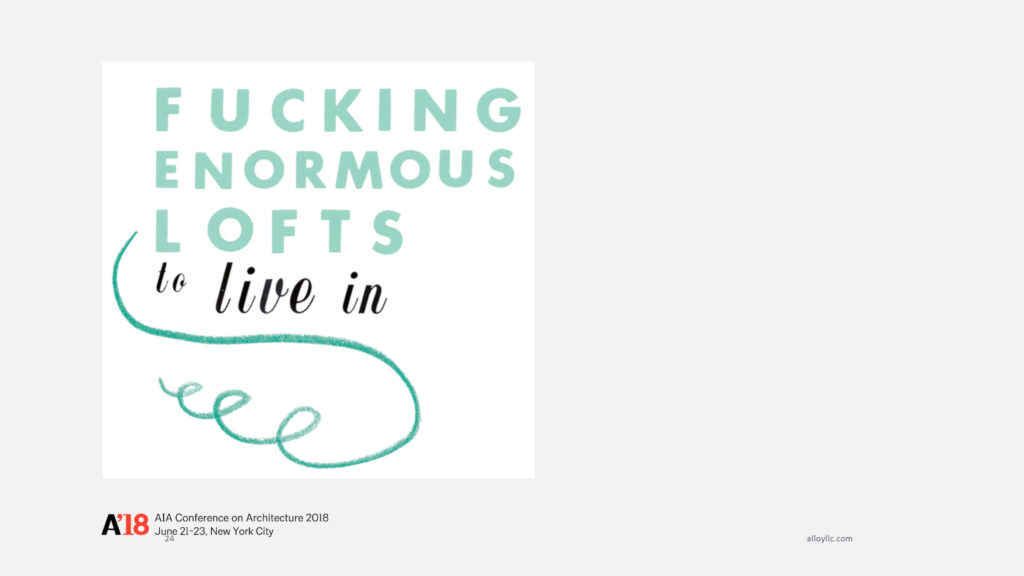

So we do things a little bit differently, and I will talk through a couple of projects really quickly. One of the beauties of being the Architect & Developer is controlling the message. This is a project we did in 2009. When the world was falling apart, we bought a small loft. We had a modest budget for the project. It was a 30,000 square foot project. We had a loft building. We bought a beautiful building. We had actually tried to buy it a few years earlier, and that buyer fell apart, so we bought it from the bank.

Then we hired a children’s book illustrator to come in. We gave him $2,000 and a can of white paint. And he literally painted the floor plans all over the whole building. That night we sold $21 million in real estate. We had one apartment left at the end of the night. It was a super scrappy way to talk about space in an existing building. It was a simple renovation in a historic district. It was one of our favorite projects in a way. It showed a re-thinking. Had we dealt with a broker, they would have said, “Well, you need a marketing brochure, you need a book, you need floor-plans, you need all this stuff.” We were like, “Nahhh, we’re not going to do that.”

So sometimes we get carried away. We recognized that we had a lot of demand for that type of product. So the next building we bought, we brought the children’s book illustrator again. He rode off on his scooter and said, “I got it! This is the perfect idea.” So he came back with this. We were like, “Huh. Maybe we’re going too far? Maybe we need to edit.” So we do have some editing capacity in controlling of the message and the idea. In this instance, we were selling space in New York City. These were large spaces with 3-thousand square foot apartments with 14-foot ceilings. We were trying to connect people to the idea of space being the most important thing. So there are projects like that.

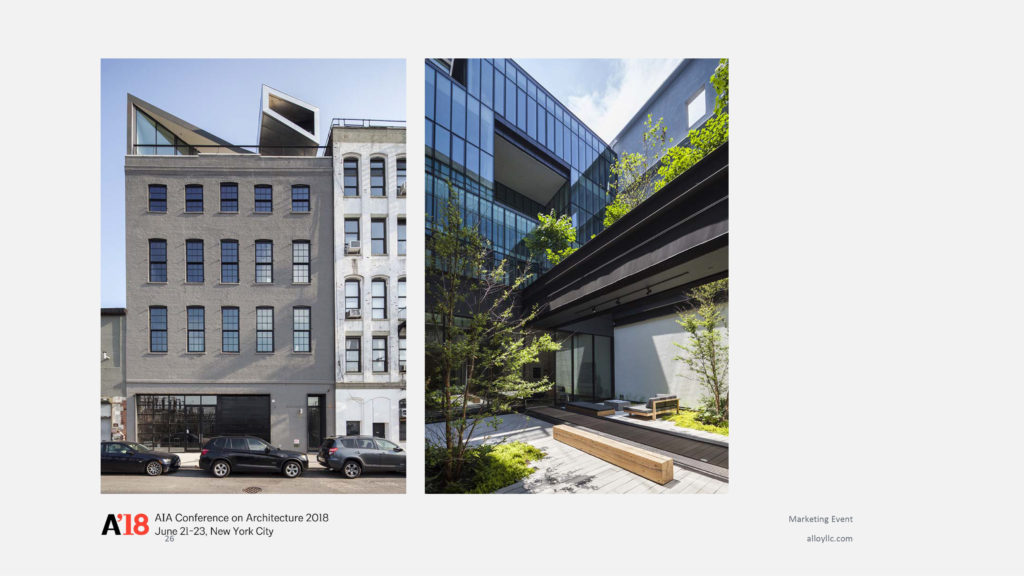

This is a 35,000 square foot project where we are doing these big apartments, and making these big decisions, some of which I might not make again. In the image on the right, we had a block through building. We cored out the middle of the building and repositioned the bulk on top of that building, which is the image on the left. It is in a landmarked district, which adds complexity when you are taking apart a building that was built in the 1880’s. Again, another successful campaign. We sold out in two-weeks with this information with just an existing building and some very simple collateral.

Over time, our projects have largely been in a single neighborhood, literally a block from my office. We can’t tell if that’s just because we’re building a reputation there and sellers are coming to us, or because we’re lazy. But this is a project we built in our neighborhood, a block from our office. It started our construction company. These are some of the first passive townhouses ever built in Brooklyn. They have a ductile concrete facade. I think taking risks like that, where we think about the history of this neighborhood, which had some of the first reinforced concrete buildings, built in the early 1920s by Robert Gair… pre-Brooklyn Bridge. We took this idea of reinforced concrete and pushed it to its limits with a product like ductile and created a new townhouse typology that looks more industrial. We took the risks on the aesthetic choice and prioritized where we would put value and how those would fit in with an existing neighborhood. Again, how we would think through delivering a product that was unique to the neighborhood by delivering something that was on the edge for sustainability purposes.

So, this is a joke, but not a joke. We started to get involved in these Public-Private-Partnerships. We were awarded a site through a public RFP in Brooklyn Bridge Park. We started to really enjoy the early part of sales and marketing. We were trying to figure out what we were trying to do here. We were building inside of a public park, so we decided to build a park in our site, while the park was in construction around us. So we planted a big field of flowers. In the end, we were like, “Well we have to take this down before we start construction. How are we going to do that?” So someone in our office was like, “We need goats.” I go home that night and my wife was like, “What did you do today?” I was like, “Well, I had to find a shepherd to sleep in the field with some goats, so that the goats wouldn’t get stolen overnight.” So we planted this field of flowers, we brought in some goats, I found somebody to sleep in the field with the goats. Unfortunately, one of the goats broke free and started running through the neighborhood. So not everything goes according to plan. It enabled us to create something that was memorable in the neighborhood. This idea that place and working in a public park was a privilege and trying to connect that to a place that had no address. It was in Brooklyn Bridge Park, so we called in the John Street Pasture.

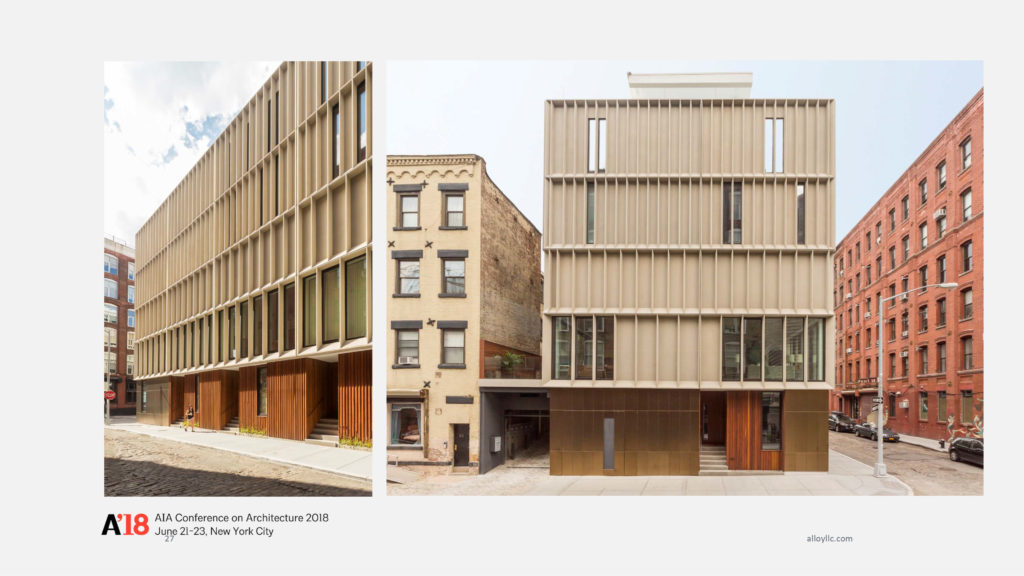

The building itself, we start to jump scale as a practice. This is 130,000 square foot building. We understand the sort of historic context of this neighborhood and the typical relationship of window typology. In this neighborhood, because you are on the river, the views down low are actually better underneath the bridge. So we pulled all of the windows forward and proud of the building. We inverted the typical relationship where the windows get smaller at the top. It starts to create this sort of double-take, where it feels like it’s part of the Landmark District. We built a really beautiful brick building. The bricks actually get smaller as they go to the top as well. It changes the nature of the reflection to a clean reflection with a broken plane rather than recessed windows which is common in the neighborhood. This started our Public-Private-Partnership model. We donated a space to the Brooklyn Children’s Museum in this. I always joked with my partner that it would be faster for us to donate a museum than it would be to get called by someone to design one. So we are starting to do that.

Community engagement has become a really important part of our practice. We don’t spend money on marketing. We spend them on the communities in which we are working. We are working on a large project now in downtown Brooklyn that is going through public review process. It is over 1 million square feet. During the process of development and while we are pursuing entitlement, we have sponsored six projects. We spent over $1 million on early public engagement. We have done everything from creating a system for court-involved youth to get diverted out of the court system through arts education. We donated a space to non-for-profits and dance and art organizations. We created community festivals. It is about this idea of building awareness in the communities in which we work to connect to people, the places we make. We are making real estate, and we are selling it, but the places we make, we want them to be valuable. We want them to have this alternative sense of value where communities can be proud of participating in them. And proud of having them as their neighbor. So the project we are working on now has a series of features which we are starting to really leverage for density for scale. On this new project, we are donating two public schools with over 700 school seats. We are creating over 200 affordable housing units. We are donating one of the existing buildings to a cultural institution. It will be over 15,000 square feet. We are creating over 3,000 jobs with that. We are swapping our property with the city for more land so that the schools can have large open-space features like gymnasiums and auditoriums which they currently don’t have. The cost of this benefit for the new project is over $230 million in public benefit, for zero dollars to the city.

Projects like this are what we are working on, which is a 980-foot tall building with another phase that is 500 feet tall. It sort of expresses to me what our role is as an architect. We think of an architect in a traditional way where we are providing services for people. But, ironically the further I get from providing architectural services, the closer I am to being an architect. The definition that is shown here, “The person who is responsible for inventing or realizing a particular idea or project” is how I perceive our practice.

Peter Guthrie – DDG

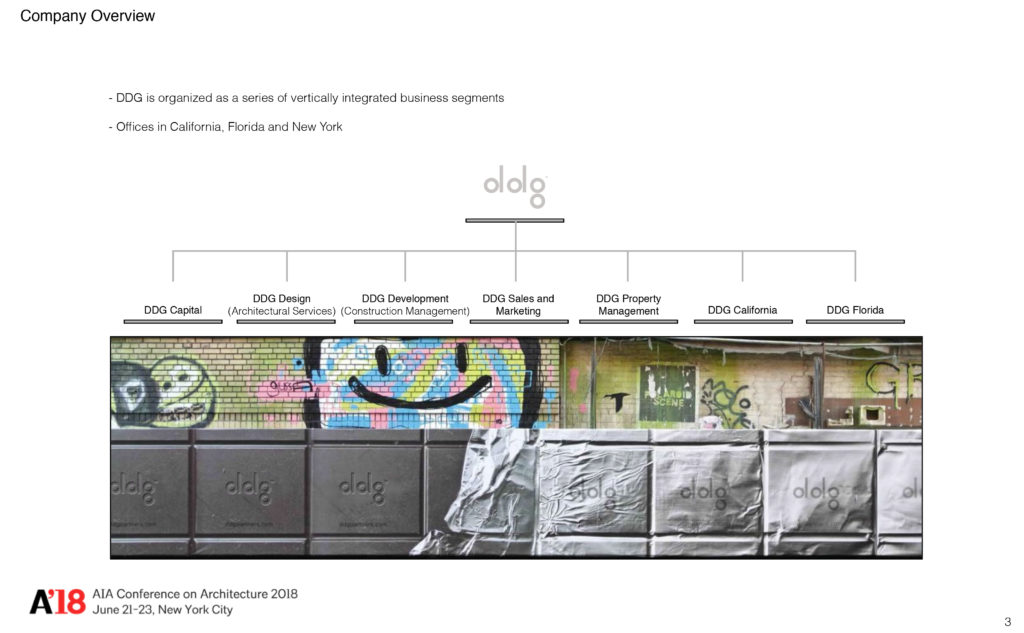

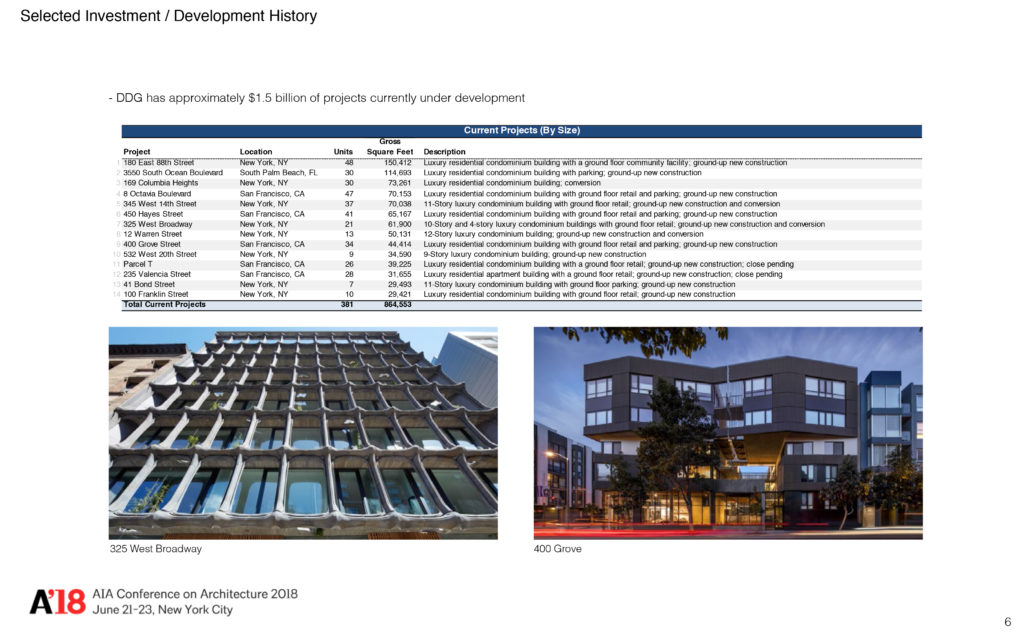

Well done, that’s a tough act to follow. I am Peter Guthrie of DDG. We started DDG in 2008 and been going ever since. We do a lot of the same things that Alex and Jared are doing. We could probably give each other’s lectures. It might be a fun thing. We will try it out the next time. We design-develop-finance-construct and then manage our projects. We are vertically integrated and this is a horizontal slide. We are doing a lot. We are building in New York, San Francisco, and Florida. We are also looking at a project in LA right now.

I studied art history and sculpture, and then went and took a Masters in Architecture. I came to the city and I did a number of things, but I was always interested in making and building. My passion is that. It is at my core. I came to the city and worked for a metal worker in DUMBO. So I know your area very well, Jared. That was super fun working for $10 per hour shaving welds. That then led to a job with Peter Gluck with GLUCK+ Architects. For those that don’t know who he is, he is a great mentor. I learned the design-build philosophy from him. I had done what I would consider design-build work. At Yale, we build a house for folks in the neighborhood as part of our first year building project. It was a great way to see a building through. I had also worked for Habitat for Humanity while I was at Duke. I think I added in my bones that you could really make a difference by getting out in the community. That was at least the difference that I wanted to make. I wanted to get out there and figure out how to get something done. When I moved to Brooklyn after working with Peter for a while and wanting to do my own thing, I, like Jared, did some work. I built a house for a friend. Then I had that same sort of feeling of dread of beating the pavement looking for a client.

So I was looking around these buildings in Brooklyn with Fedders air conditioner units in the windows and thinking, “What are these guys doing? What is the secret? How could we do a development project?” I was talking to some guys in the neighborhood and it came down to something that certainly wasn’t rocket science. “300! 300! 300!” I was like, “What’s that?” “You buy it for $300, you build it for $300, and you make $300.” And it’s that dumb and that simple. The pro forma was a back of napkin idea. You buy it for X. You build it for Y, and you sell it for Z. Hopefully, you have done your math correctly. I had done that already on a very small scale. I built a desk. I bought the wood myself. I could break it down, and I think all of you guys, those of you that have studied architecture, have a great skillset to break problems down into very simple components and not get overwhelmed.

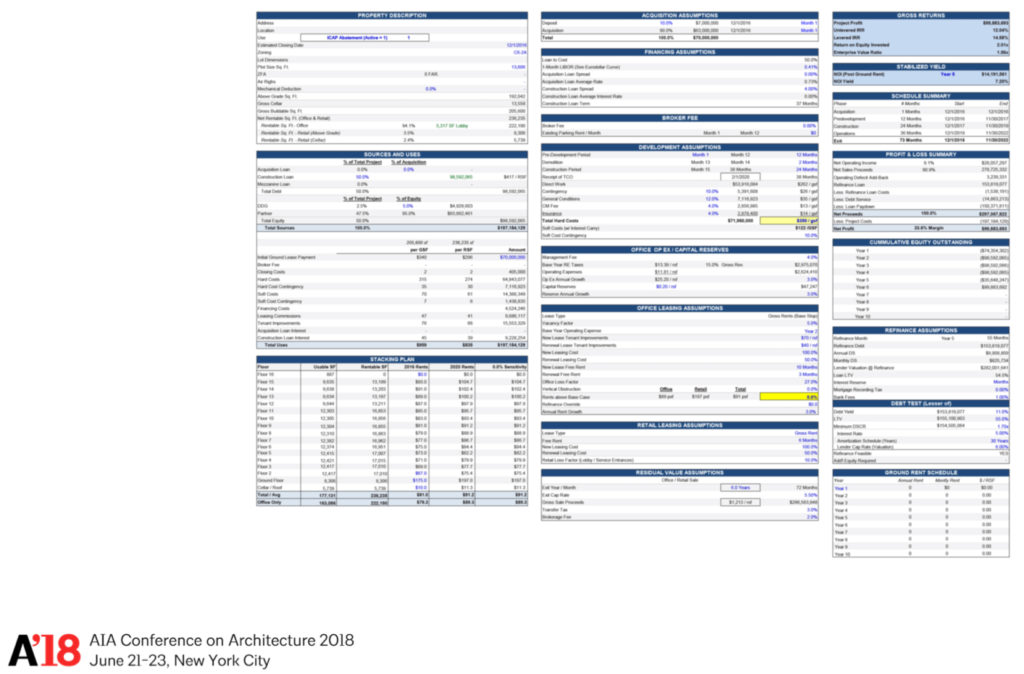

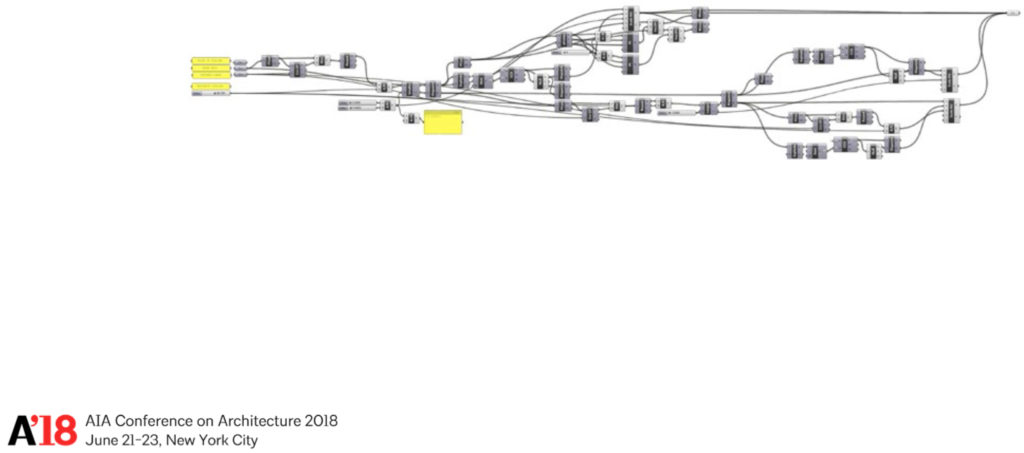

This complex thing that is blurry… and I hope you can’t see it specifically… because it may be confidential… it has a series of parameters. I have a slide later on which I love. It is my grasshopper script slide, which is parametric design thing. We use it. It’s fun. It’s essentially the same thing. Architecture, and many things in life are a set of parameters. What you do those parameters and all these little toggles are related to time and money. Lurking beneath all those numbers are choices. There are a myriad of choices that you can make. That is the fun of it for me. Every day, I wake up thinking of the opportunities that are going to be on that day. In talking to a banker, talking to an electrician, talking to one of our architects, talking to one of our construction managers, talking to one of our building managers.

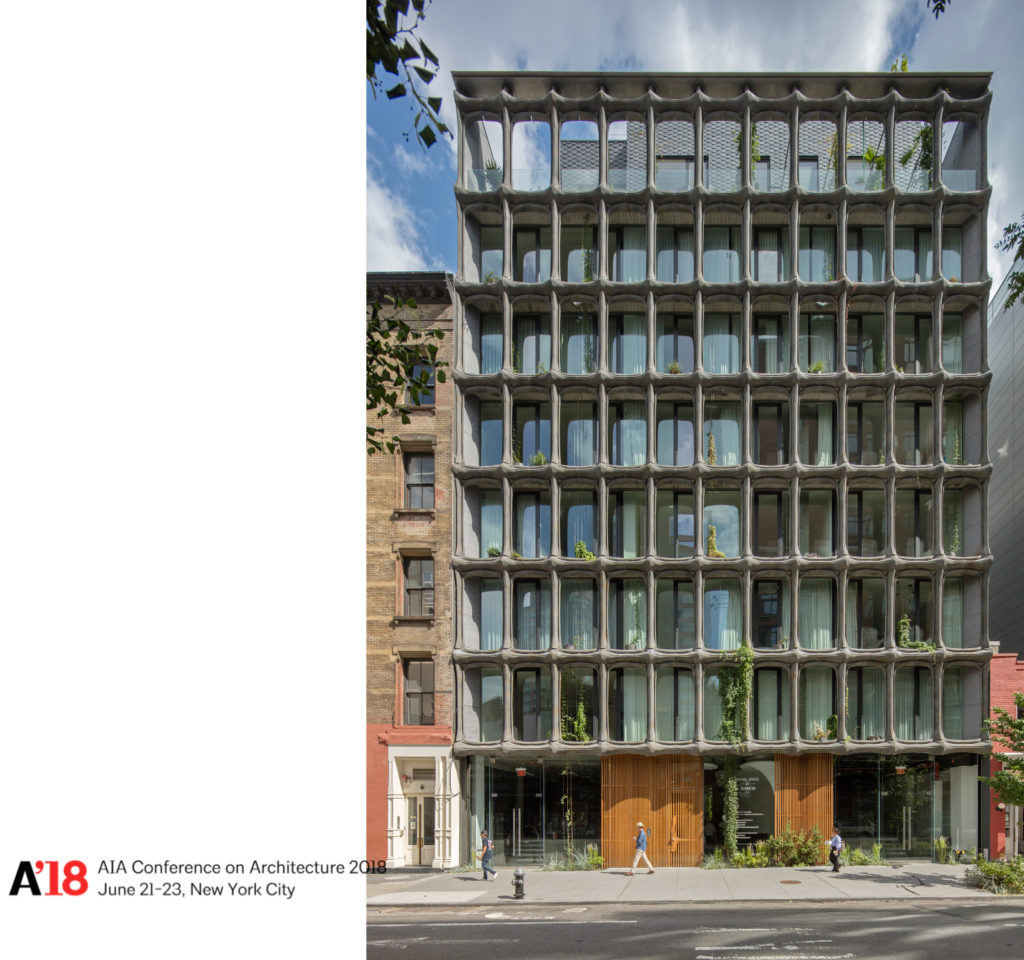

So this is our first project in Manhattan. It’s 41 Bond Street. It is a bluestone building. It is in a Landmark District, so we had to come up with a way to make a ground-up residential building in this Landmark District with the auspicious start of being right across the street from Herzog and de Meuron, and my old professor Deborah Berke. It was just not where I wanted to start. I go to the site and I see school groups coming through and they’re all oogling at Herzog and de Meuron. I love their practice. I know there are money people who don’t love that building, but I do. I love that building. It is something that I could never make. We knew we had to do something different. We needed to be chilled out and respectful to this neighborhood and try not to draw too much attention to ourselves. So we buckled down and found a material, this bluestone. We had done a building down in TriBeca already, so I already had my feet under me. It was still standing, so we thought we could keep going. What we did was take craftsman… and one of the secret little weapons we found in the numbers is the labor. I agree with Jared. Unfortunately, on this project we are working on right now in the Upper East Side, we have become the concrete contractor. I didn’t get into it to want to control every little piece. But you do find that it is to your advantage. So we have our own masons. We bought the stone and we shipped it down and we would cut it and carve it on site. Not radical craftsmanship, but just a step that is really hard to get in the direct marketplace if you don’t have direct labor. It is a rigged thing. By having direct labor, we can pass that profit on to the project itself. We are not taking that profit and putting it into our pocket. We are putting that profit into the project.

That is Mickey over there on the right putting that door frame in. We did everything on that project from soup to nuts. From the facade, we put in all the windows and all the interior framing. All the bathrooms, and all of the trim. All of the specialty trades. This is a team that I had built up over the previous 5 years before starting DDG. Again, getting into it from one guy who I hired as my grease, my general conditions, just to go around and help the other trades. We found that the other trades, like my door guy was not making it. He was just not getting the doors in and plumb. So I would ask Juan Carlos to go and fix it. Suddenly, there was somebody else we needed to bring on. We became, on the next project, the subcontractor. We did all the framing and all of the specialty trades. We got so tired of fixing other people’s work, and we were finding that we were training our own crew. That is a drawing on the wall. We like to break down the mystery… and I learned that from Peter Gluck a lot. We really labor over how to communicate, how to break down the barriers of this world of architecture and design and make it something that is more collaborative. We find that that interplay between all of these specialist or these artisans, our tradesmen, is essential. It results in a fantastic and unexpected interplay, where our details get better and better.

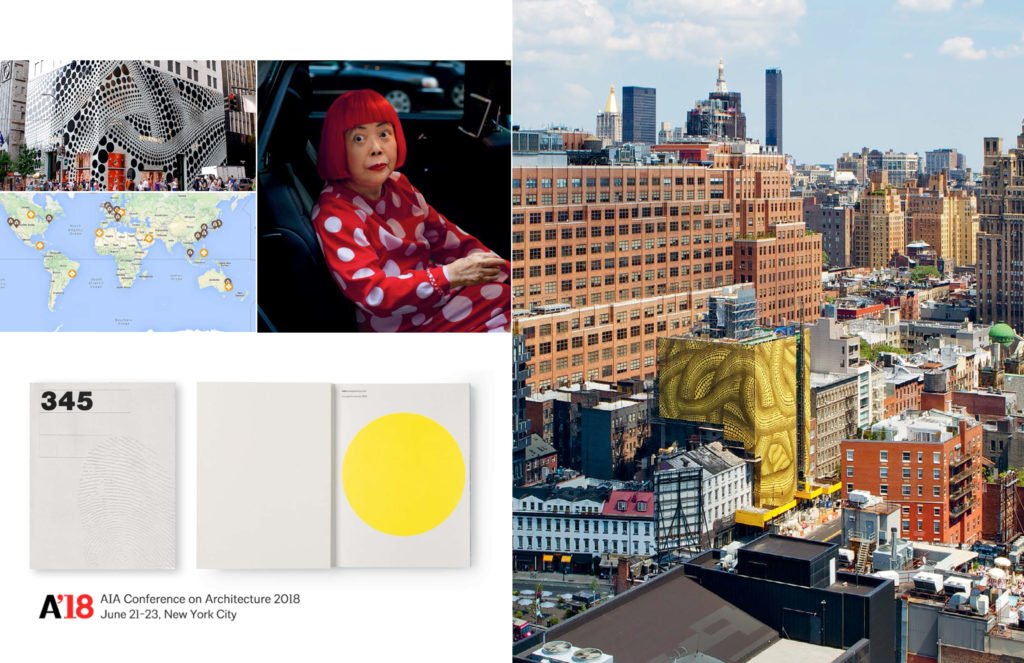

Jared is way ahead of me on this platform. You [Jared Della Valle] are really in an admiral place in terms of the community work that you are doing. We are just stepping into that field. This was a start for us, where we realized that there was something that was happening that was a little bigger than us. We could provide a platform. That platform could be synergistic and be win-win. We built a building in the Meatpacking District. We came up with an idea. I just asked a question. We had these mesh wraps that go around the scaffolding, a black mesh. What if we did something different? We could tie that to our marketing. Yeah ok. We could design something… in fact, we had already designed a sort of thumbprint thing. Then we asked another question. Who could we partner with? The Whitney was just moving downtown. Does anybody know anyone at the Whitney? My partner Joe did know somebody at the Whitney. So we talked to them and Kusama. They were having this great exhibition of Yayoi Kusama. It just so happened that the exhibition was coinciding with Louis Vuitton opening up 450 stores worldwide. We couldn’t have imagined a more incredible marketing boom to tie our building to the Whitney crossbreeding opportunity.

It turns out her studio was on 14th Street. Her dots sort of connects to the hallmark of this building, which are these bricks that you make. The guys making these bricks, and I have been over there to see the guys making them, as he is taking the mold out around the brick, leaves a little thumb depression in there. You can see it on the right. It is so sublime that you will never see it. It is buried in the wall. It is this incredible enigmatic touchstone of the human component of these handmade bricks that come from Denmark. To me, that little thumbprint connected to Kusama’s dots, which was this sort of invisibility shield.

325. Some developers, not these guys [Alex Barrett and Jared Della Valle] will often look at this area as another one of these places to try and get around something. Oh, they’re smarter, they’re going to get under and around and play the system. We took a different tact. We said, “There are architects sitting in this room who are going to judge this project. What if this was a collaborative enterprise? What if this was like a crit back at school?” We went kind of overboard in making basswood models and looking at the tectonics. This building is in SoHo, so it is in the cast-iron district. We looked at the history of cast iron and component parts. We thought deeply about it. We entered into a discussion with Landmarks and showed them what eventually becomes a building… while trying to reinvent a language that is connecting to the cast-iron district.

We end up working with the ZZ Top boys. They were awesome. They make chevy engine blocks in the middle of Pennsylvania. They were fantastic. They couldn’t believe that we wanted a weird burlap texture to our aluminum. We were gravitating to these pieces in a cart. They were the rejects. They were so used to military specs. This is us playing with the modeling and the finishes. This is the texture, a burlap finish. All of this craziness was supported by New York City Landmarks. It was a fantastic process. It was heavy. They had great feedback. We allowed the process to force us, but they were instrumental in making us try harder and made the details for architects in many ways. That was fun to realize. They really wanted to look at how the side of the building and our aluminum screen integrated. I thought, “Man, that is crazy. The Landmarks is totally having a modern architecture dialogue.” It was not what you would expect. The knee-jerk anti-modern rhetoric or stand that some people expect from Landmarks.

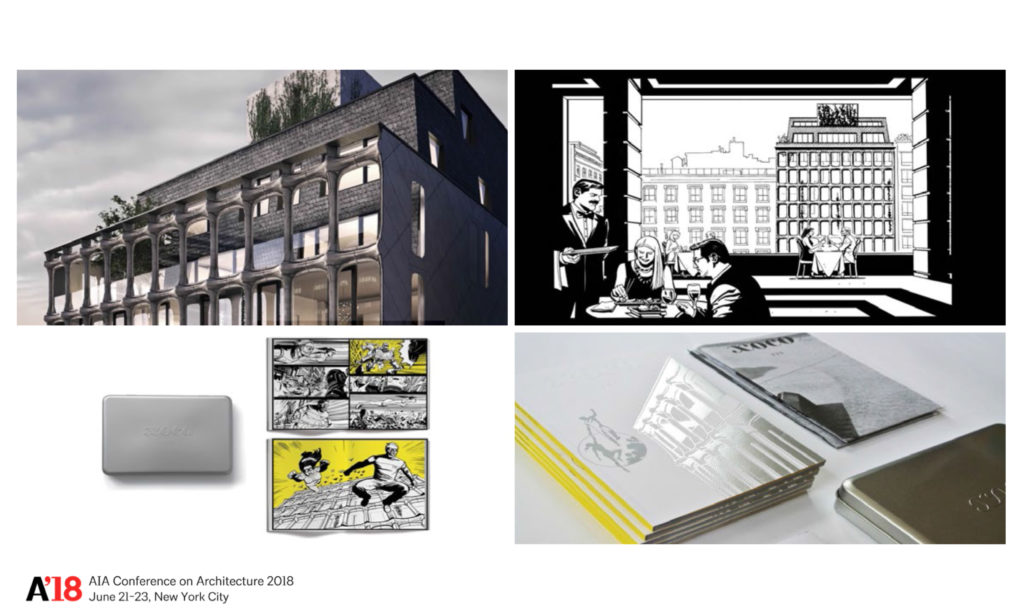

Our marketing… like the Kusama, we are partnering with Shawn Martinbrough, who had just given a TED talk. He is doing something the George Lucas now. He is a noir-comic-artist. He was instrumental in helping us find a story. Like what Jared was saying about creating opportunities outside of the traditional selling model, that was the thing that we learned form Kusama. In all of our projects, we do partner with other artists or artisans. We make books for them as well. They’re artworks in of themselves. We will do crazy things, like a billboard.

This is a story because this was an old chocolate factory. So we came up with a storyline of these two heroes who have to battle an evil robot. Ultimately they save the day by saving this chocolate recipe. I dunno. Somehow it made sense to us. Why not have a little bit of fun? It is tangential marketing. You will see this in luxury goods and Louis Vuitton and these Gucci places. Ferragamo had some illustrators do work. We are riding on that wave. I think that tangential marketing and the spirit of collaboration is what drives us. What I didn’t show earlier, is that the Kusama collaboration ended up influencing our grill design. So our HVAC grills in the apartments are this dot matrix that we would have never have thought about had we never partnered with her.

This is a building in TriBeCa. More bluestone. It was fun. We laid it out in a field in Long Island.

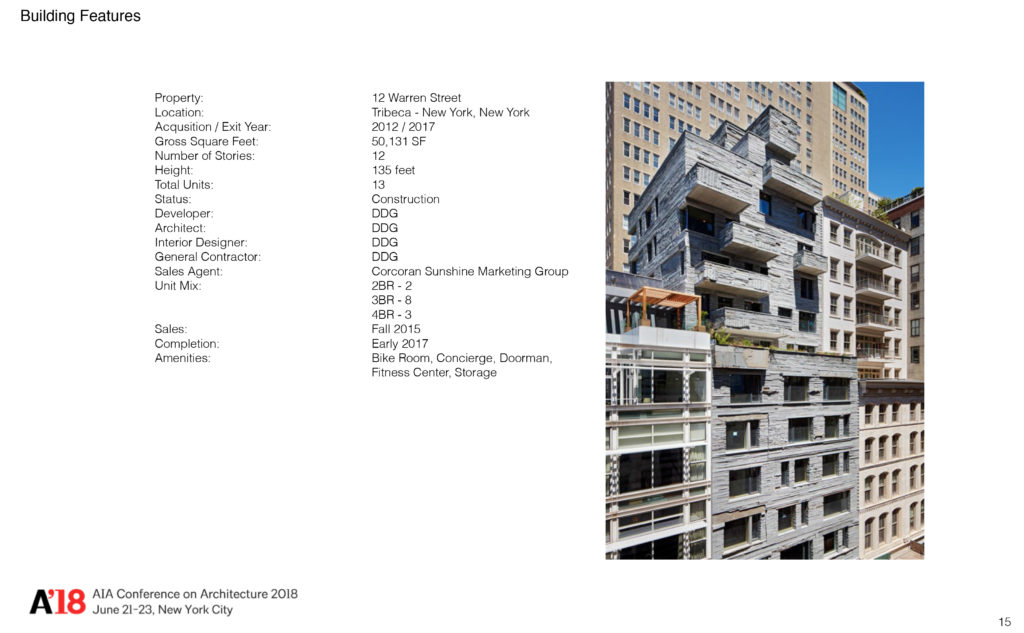

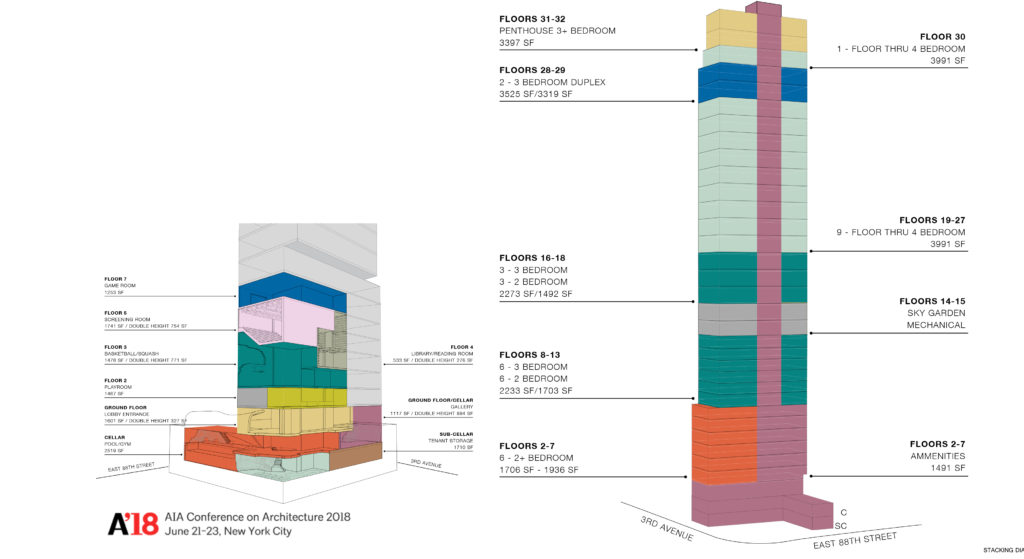

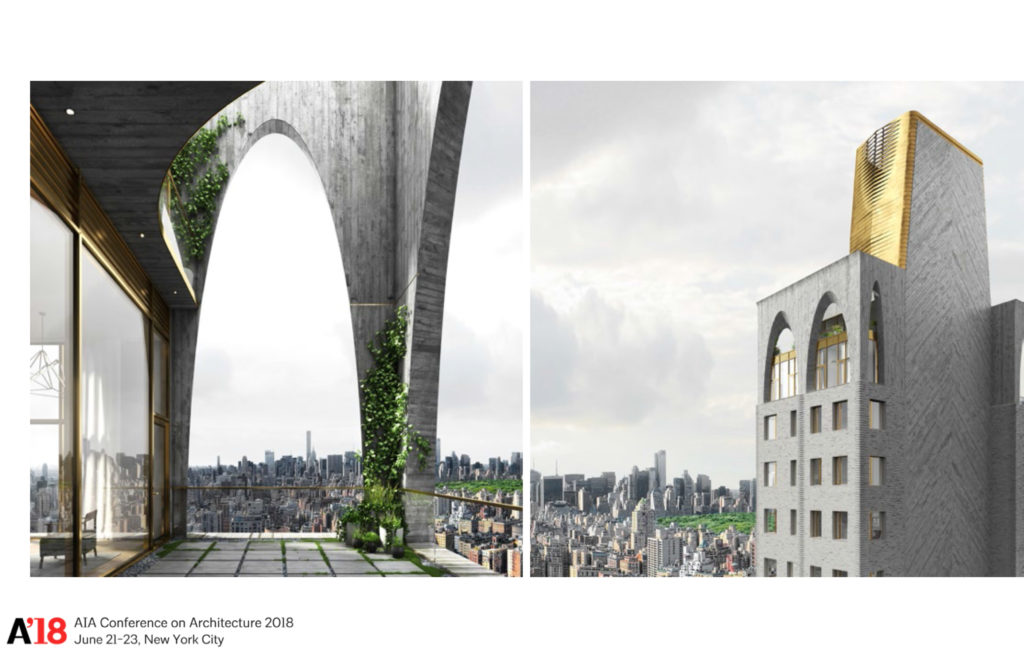

88th Street is a tower that we are doing on the Upper East Side. We do a lot of studies. These are the stacking plans of how many units. It is primarily residential with a commercial component on the first floor. This one was weird. It has this whole amenity package, which turned out to be more or less necessitated by the form and the percentage rules governing that site. It forced us into making all of these amenities. Modeling. We do a lot of 3D modeling.

Here is my favorite grasshopper script. That is crazy. I love it. This is the mess of the parameters. Then it results in this, which is actually the fenestration pattern. It literally tied into 10 percent and the different percentages of legal light and air for different rooms. Whether it be secondary bedrooms, bathrooms, or living rooms.

This is our brick mock-up. This is our artisan Jan Hooss, working in stucco. We like to go macro to micro and find that these very micro collaborations work their way back into the macro. These are the arches in the top of the building. We are currently on the 28th floor, and there are 31 floors. So we’re getting close. Brick started.

Just leaving you with this last slide of the sales gallery. This is Stephen Quinn on the right, who wrote the book on dioramas. He is the foremost diorama authority. He works with the Museum of Natural History. When you go to the Museum of Natural History, he has a book in there. It’s fantastic. We needed to make windows in the sales gallery. Many people are offering these digital prints. We said, “Nah, that’s crazy. Let’s talk to the folks at the Museum of Natural History.” Sure enough, they were really interested in partnering with us and we made this diorama of Central Park. For me, it is that touchstone of just asking a question, “Can you do this a little differently?” If you approach it with some great people and some passion and energy, some fun things can happen. Thank you.

James Petty – Architect & Developer

I just wanted to talk about a few things real quick. What these guys are doing isn’t new. I know that the AIA hasn’t talked about it for a very long time, but in 1777, John Nash took a lease assignment on a piece of property in London and developed 8 units. That was 241 years ago. He later designed the Royal Pavilion in Brighton and Buckingham Palace. That is what you probably know him best for.

So how do you do this? I want to break this down into a couple of quick steps for somebody who is an architect trying to get into the development.

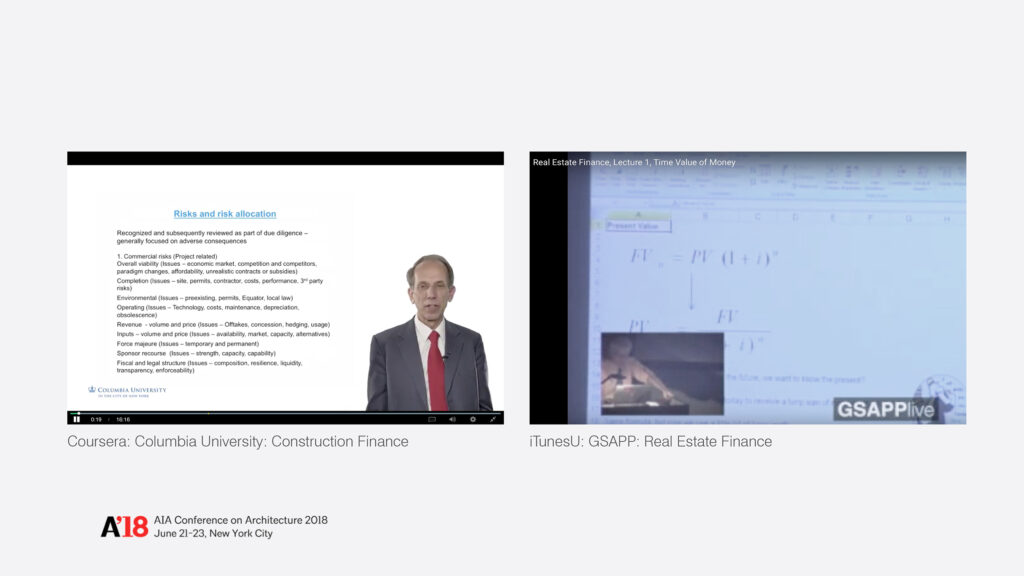

The first step is that you’ve got to educate yourself. You need to take the time to learn a lot. There is a lot of terms that you need to know: the NOI, the ROI, the NPV, the IRR, etc., etc. You can get a real estate degree, but there are a lot of universities who are starting to put more of their content online for absolutely free. Coursera, EdX, and iTunesU are fantastic resources [more info here]. They may sometimes look like they are behind a paywall, but if you work your way through it, it is free. The Real Estate Finance course by GSAPP is really one of the greatest things to start out on. Pro formas. You need to learn how to read them. You need to learn how to take them apart and put them back together. But really, it is a simple process. You buy it for X, you put in Y, and you get out Z in the end, but you need to understand what that process is.

Real estate is a debt-financed industry. If you have student debt, you need to get it refinanced. If you have bad credit, you need to get it fixed. You need to put yourself into a situation that when you go to an investor or a bank, they see you favorably and they will give you money. You also need to start putting money together. You are going to have upfront cost for land acquisition, consultants, and entitlements before you will ever pull a construction loan or get an investor to put money into your product.

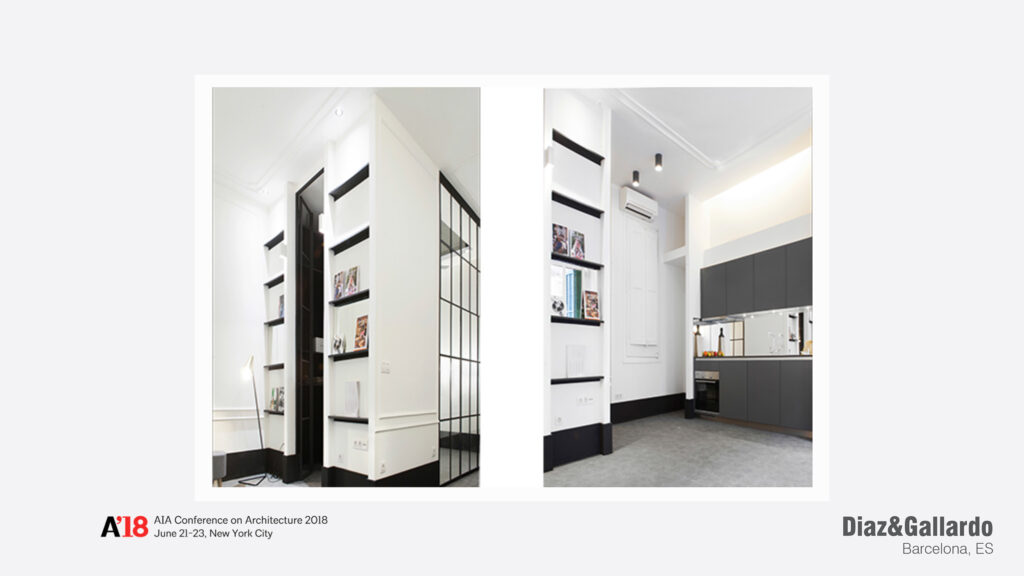

You need to figure out what you want to do. These guys [Alex Barrett, Jared Della Valle, and Peter Guthrie] are doing big projects that cost a lot of money, but a lot of people are starting out in smaller ways. Diaz & Gallardo is a couple in Barcelona who lost all of their clients in 2008. They started buying small apartments and renovating them themselves. Now, they’ve decided that they don’t want clients anymore and they keep doing this. They’ve done over a dozen.

Jose de la Cruz borrowed money from his brother and his 401k. He bought a house for $80,000, put $80,000 into it, and sold it for $280,000. All while working a full-time job at an architecture firm. So his day-job Monday through Friday. He worked on this house Saturday and Sunday, and he still doubled his money on this guy. He is working on his next one now.

You can do a new build. Mike Benkert also has a full-time job. On the side, he bought a $25,000 lot at a sheriff’s sale. He works nine-to-five, and on his lunch breaks, he checks on his contractor building his project. This is his second house and he’s getting ready for that third project. It is important for him to keep his day job for the financing. Banks need to know that they are going to get their money.

This is The UP Studio here in New York City. They are a young couple of guys doing a lot of interior work. They wanted to do a modern house. Nobody was hiring them to design a modern house. So they bought a piece of land and did it themselves. While it was under construction, they had several people walk by. They said, “I love your house. I’d love to hire you as my architect.” Now they have several projects. They are making legitimate buildings and they are on to their second development.

Multi-family is tough. What these guys [Alex, Jared, and Peter] are doing requires a track record and to be heavily capitalized. This is Cary Tamarkin. He has a lot of projects on the High Line. They’re beautiful. Like I said earlier, if you go to bit.ly/archdev, you can download a map onto your phone, and you would be surprised by how many buildings are actually developed by architects.

With multi-family units, pre-selling is a really big deal. This is a great example of where you can be clever. To be an Architect & Developer, you need to set up a lot of entities and a lot of contracts between yourself. Onion Flats was able to get the

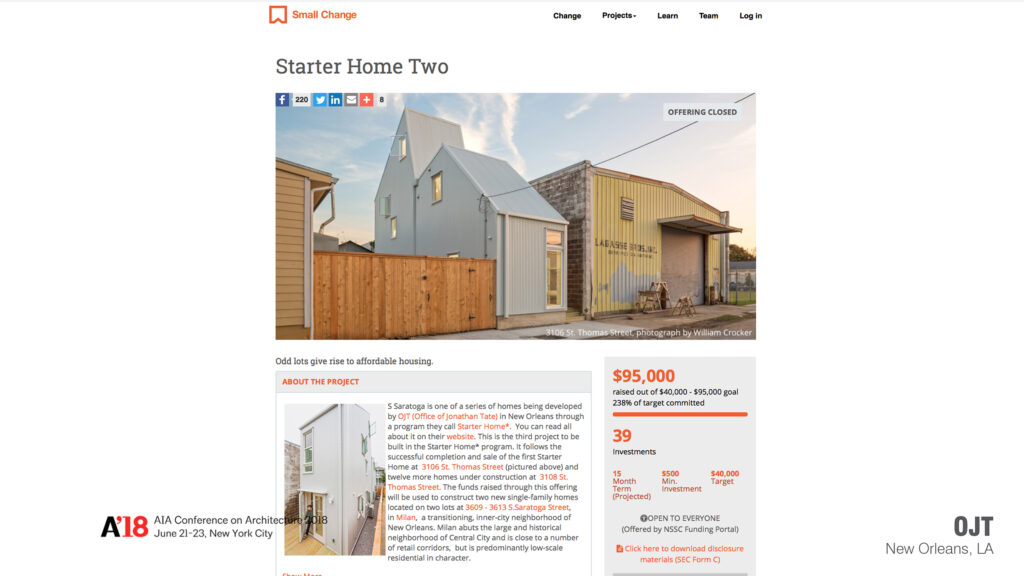

You can also play with your own academic ideas. This is Jonathan Tate down in New Orleans. He started with this little sliver house on the right, which has been getting a lot of press lately [see here]. While that was under construction, which he developed, he bought the land all next to it. Zoning gave him the right to do three single-family houses. He didn’t want to do three-single family houses. He was interested in a tighter, denser neighborhood in New Orleans.

So he created a co-op on the land which allowed him to create ten detached units. It created a really interested little network in what he calls Starter Home*. It is an academic exercise for him that has also become lucrative.

In downtown San Diego, there are these three guys [RAD LAB] who had a thesis project to create an urban park. They wanted to create it with no money… because they were in grad school. So they raised $60,000 in a Kickstarter to pay for a bunch of up-front fees. They went to the mayor’s oce. They said, “Look, we were able to raise a bunch of money, can we get something from the city.” So the city pitched in. They gave them a 2-year lease for cheap on land that was later to be developed. Then they got some investors. They got each one of these tenants to sign up. They made the tenant pre-buy their shipping container and pay RAD LAB to design the thing. So RAD LAB was off to the races without much money. Now, each of these tenants pays RAD LAB rent each month.

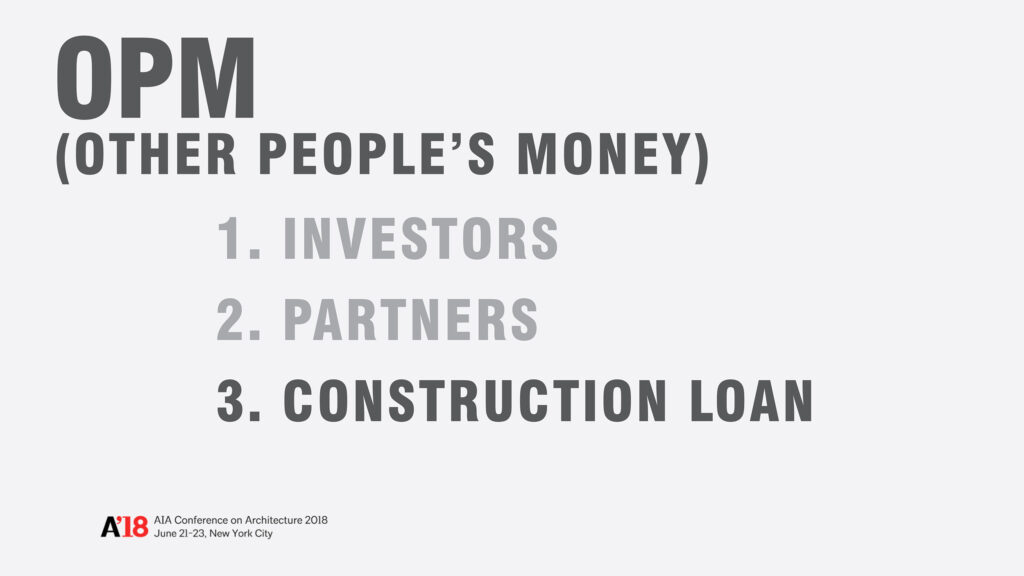

So this is great. What these guys [Alex, Jared, and Peter] showed you was great, but then there is the real reality of the situation, right? [I am an architect. I have no money] So, how do you figure out your financing? The truth in real estate is that nobody has any money. It is always other people’s money.

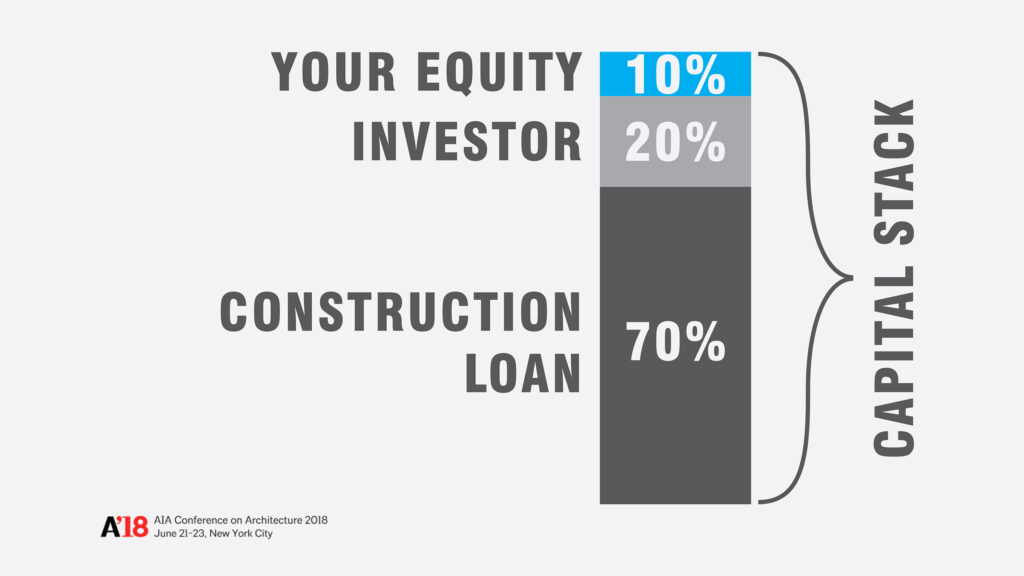

You need to find investors. Maybe that structure is something along the lines of offering a 10 percent preferred return and split the profits 50/50 afterwards. Maybe you get a partner where someone else comes in and puts in all of the money while you put in all of the work. In the end, maybe you get some money out of it. Or you get a construction loan, which might have terms of 4 to 6 percent interest (although that is getting higher these days). They will give you up to 70 percent of the cost of construction. They aren’t going to give you all of what you need, which means there is still going to be a gap in what you need. That can be problematic, because you still have to ll in that 30 percent gap

This is where you get creative. You use your skills to create what is called the capital stack. There are a lot of ways to do this, but this is just one way. You get a construction loan, find an investor to bridge the gap… which is a loan on a loan… the risk is higher… but you decrease your equity to 10 percent. This is a very real scenario of how people develop real buildings. But how can you get that equity even lower? I have a few little thoughts on that which I want to share with you today.

One of which is architecture is equity. When you have all of these diferent entities, and they [Alex, Jared, and Peter] talked about that before, you can use your fees as an architect that are early on towards your position in the loan. Banks will recognize that, so long as you create a paper trail. Contracts with yourself. “Money Days” like Jared was talking about.

Another idea if you want to take a little bit less risk is that if you have an existing relationship with a developer, you can do what GLUCK+ did. We put in sweat equity into the front end of this project. Basically, the architects worked for no fee for a percent stake in the ownership of the project. This is a rental project in Philadelphia. Now GLUCK+ takes in a percent of the rent every single month. You have to realize that for a developer, all of the fees at the very beginning of a project, which is when an architect does most of their work… before entitlements and before public permissions… is the most at risk for a developer. That is when the architect is most valuable. If you are able to work out that kind of an agreement, it also means that if the project doesn’t go through, you don’t make any money.

Crowdfunding is a very interesting thing that is going on right now. There are a couple of reasons why. This isn’t your Kickstarter. It is a little bit different. There are a lot of projects that you see on Kickstarter that never gets built. So much wasted money. ZUS is an architecture company it Rotterdam who wanted to build a bridge. They raised 100,000 Euros by ofering to CNC route the names of the donors in the walls. The city was like, “Great! People actually want this thing and are willing to put their own money into it.” So the city put the rest of the money up and they built the bridge.

This is the REAL type of crowdfunding that is going to come into play. Before 2012, in order to become an investor in real estate, you needed to be an accredited investor according to the SEC [Securities and Exchange Commission]. This meant that you needed to be worth more than 1 million dollars. Since then, the JOBS Act has been passed. Every single year, that regulation has been coming down to the average person to where a regular person could invest $500 into a project. That is what Kevin Cavenaugh did. This is not a rendering, it is a real building in Portland. He spent 15-months and $200,000 in attorney fees to get SEC approval to be able to crowdfund this thing. But he was able to raise $1.5 million as part of his capital stack. Which is pretty incredible. This project just finished construction a few months ago. In December, he did a second crowdfunding campaign. He was interested to see if investors would take less of a return for a social cause. His next project is housing that subsidizes homeless housing in Portland. He offered investors a 5 percent return, which is very low. Within 3 days, he was able to raise the $300,000 he was looking for which proved his point that people were willing to take less of a return for a social cause. It is pretty interesting.

This is the next level. This is regulation CF of the SEC JOBS Act. This is Jonathan Tate again. A few months ago he was looking to raise $95,000 as part of his capital stack. It was $95,000 of crowdfunding, $40,000 of his sweat equity as an architect, and $400,000 of a construction loan. Except instead of having to go to the SEC, he partnered with the website Small Change. It is a website which you can register on. They are already an accredited investor. He didn’t have to do any kind of upfront legal work. He just raised the money and now he is building the building with very little of his own money in it.

Another program is the FHA [Federal Housing Authority]. Everybody needs somewhere to live. If you are willing to live in your project, you can actually purchase and finance construction of a building with 3.5 percent down. That is what Zeke Freeman did for his very first project in Denver. This is his own house. He got a single loan that was $130,000 for the property and $100,000 for renovation to do whatever he wanted as an architect. It cost him less than $8,000 all in.

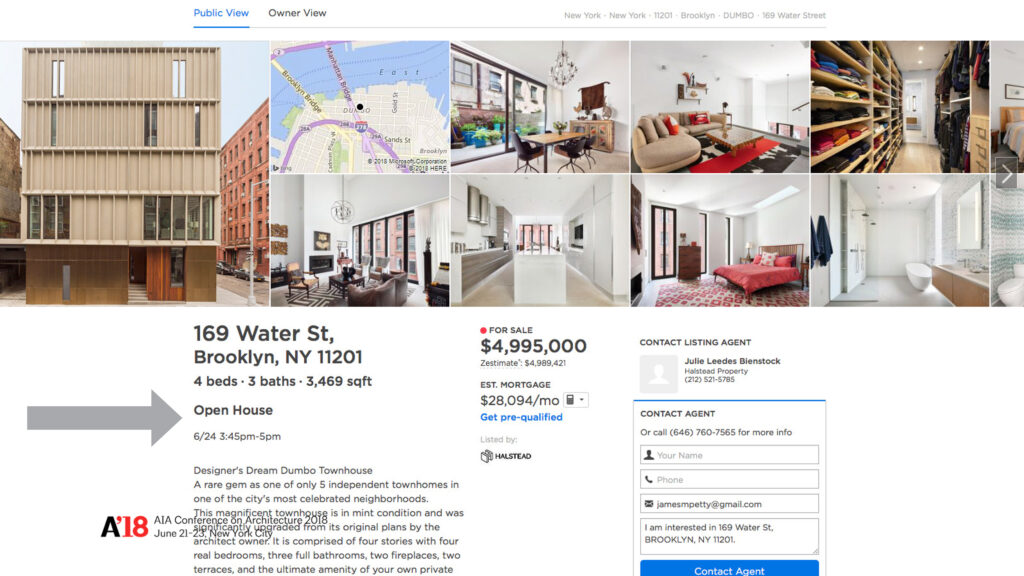

The next step is that you need to understand what the market is, what people are buying, what sells, and what people are missing in what they’re selling. The best way to do this is to go figure out what other people are doing through open houses. Sorry, Jared. Forget the AIA tours, one of Jared’s projects is having an open house on Sunday at 3:45 pm. This is all public knowledge. Just go out there and find the buildings that you admire, and go see them! For those of you not from New York City, look at the mortgage. That’s monthly.

The final step of this process before you get going, is to really try to understand the pro forma. You buy it for X, you put in Y, you sell it for Z. You can download some of these pro formas online, like the ones here form Guerrilla Development [see here]. You need to be able to go through them, take them apart, and put them together. And you need to do it again and again and again. By the time you go to a bank or an investor, you need to prove to them that you know what you are talking about and you know that they are going to get their money back, and they are going to make some money in the process.

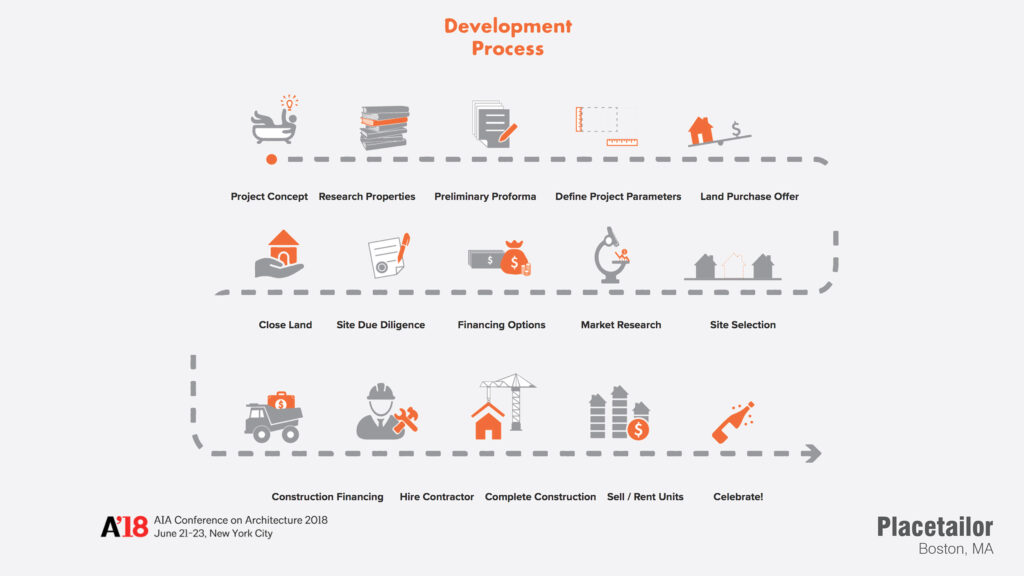

Placetailor put together this diagram. So that’s it! You rip off the bandaid. You figure out what you want to do. You figure out how much it is going to cost. You look up a site. You organize the finances. You close the site. You get a contractor, and you go make money! When you sell, the loan gets paid back, the investor gets paid back, and you get whatever is left in the end… if there’s anything left in the end. Which is a risk.

Written by Luis Gil & Richard Peiser

While architects are responsible not only for the design of buildings but also for their economic performance to the extent that their designs meet the demands of the marketplace, it is the building developers who reap the vast majority of the rewards.

Developers conceive the projects, select their locations, acquire the land, determine the target market, obtain the financing, oversee the design and construction, and lease-up or sale of the completed building. Because they do not take the risks that the developers do, architects rarely capture a significant share of the value created by their designs. Based on the AIA Firm Survey 2012, for instance, the overall cost of architectural services averages 6.1 percent of a project’s total value. Assuming they get a ten percent profit margin, the net value of these services for architects is well under one percent of total construction costs, putting them near the bottom of the pecking order of the building industry, at least economically. This compensation is at odds with the outsized role that architects typically play in the development of a building project. As a result, for many practitioners the profession is one of long hours with relatively low pay.

Architecture graduates can typically expect to earn less than their peers in other fields with comparable schooling and for many securing a full-time job comes after a slew of unpaid or underpaid internships. The prevalence of design competitions make it so architecture firms must sometimes work for free in hopes of landing a commission, and often times firms find themselves relegated to the role of consultants instead of exerting meaningful leadership on building projects. Such are the common gripes with traditional architectural practice. There is, however, a different path. The architect-as-developer business model provides an attractive alternative to this traditional method of practice. For the architect, the architect-as-developer practice model presents an opportunity to exert greater project leadership, have more freedom in the design process, have more control over what is built and the quality of its finishes, and, of course, make more money.

The idea of an architect acting as her own developer is not new. John Portman, for example, has been championing this business model for decades. Additionally, a quick Google search of the term “architect-as-developer” leads one to the website of Jonathan Segal, a San Diego based architect-developer who has been holding popular seminars that promise to teach architects how to develop their own projects for years. While not new, however, the practice model is rare. Traditional architectural pedagogy skirts the issue of money, choosing instead to focus on the development of the art of architecture. For many, this mindset carries over into professional practice. In architectural circles, money has traditionally been an issue that is seldom broached. However, in the wake of the Great Recession — and the resulting erosion of the architectural profession and its earning potential — this has begun to change. There is a growing interest on the subject and alternative methods of practice, both professionally and in academia. Indeed, the Perspecta 47 edition of The Yale Architectural Journal, “Perspecta 47: Money,” was devoted entirely to the subject. Courses on alternative practice methods are also becoming more popular at architecture schools.

“When I went to school, ‘money’ was a dirty word, and nobody talked about it” says Alex Barrett, principal of Barrett Design and Development, and architecture and development firm based in Brooklyn, New York. “And it’s great that we talk about the economics of architecture and design because, at least in my experience, in school it just didn’t get talked about.”

Last fall, Barrett, Jared Della Valle of Alloy LLC, and Cary Tamarkin of Tamarkin Co. took part in a panel discussion at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD) to speak on the architect-as-developer business model. In front of a room overflowing with architecture and real estate development students, the three presented the work of their respective firms and spoke openly on their decisions to pursue this unorthodox business model. All three firms practice architecture and development in New York City. While each firm operates in different sub-markets and at different scales, however, the three practitioners were all driven to begin developing their own projects for similar reasons: a general discontent with their experience with traditional architectural practice and a desire for greater control over and compensation for the final outcome.

“I started to become disaffected with the practice of architecture,” says Alex in describing his motives for pursuing development. Before founding Barrett Design and Development in 2005, Barrett spent seven years working as an architect at a number of firms in New York City. It was this experience that drove him to find another way. “Architecture as it is practiced today has a variety of challenges. It tends to be a quite passive profession in the end; we’re always waiting for a client to walk through the door with a project and a site and a budget, and we don’t really have too much input on those things. And that was something that started to trouble me.” As a result, he decided to strike out on his own and pursue a different method of practice. With the help of friends, Barrett bought a rundown row house building in Carrell Gardens in 2005 and began practicing as both an architect and a real estate developer.

Since its founding, Barrett Design and Development has completed nine projects with two more in the works. Operating in Brooklyn, the firm has specialized in condominium projects, with the project sizes to date ranging between 6,000-24,000sf. The firm is now working on what will be their largest project to date, a seven-story, 35,000sf condominium building in Crown Heights. Just about all of the staff at Barrett Design are trained architects, and ten years in, the firm has an impressive track record. “We are proud of our results,” says Barrett. “We have had good financial returns in addition to creating buildings we are proud of.”

The firm has returned an average IRR of 37.76 percent to its investors since its founding, a point that Barrett, understandably, is not shy about disclosing. To date, the firm has invested just over $23 million of investor equity on current and completed projects “from an ever increasing pool of people I like to call friends,” says Barrett. The firm has achieved an impressive 102.13 percent return on equity on its completed projects and is expecting to reach similar levels on its current projects. Total project costs for the firms completed projects have been approximately $51m with gross sales just above $71m, $14.6m have been profit. The firm’s focus on design as a value driver is a tactic that has clearly worked well for Barrett.

For Jared Della Valle, co-founder of Alloy LLC, the move into development also seemed like a natural next step. “I like to say I quit architecture,” says Jared. “It was difficult to say I was an architect-developer because everybody thought it was some ‘light’ form of development. And if I said I was doing development everybody thought I quit architecture. It was easier, to a certain extent, to just say, ‘we’re a development company. ” Before co-founding Alloy LLC, Della Valle was one half of Della Valle Bernheimer, an architecture firm he co-founded after architecture school. While successful, his desire to have greater control over the building process and capture more of that value his designs created led him to leave this architecture firm to co-found Alloy LLC. Founded in 2006, the company has completed eight projects to date, and has steadily grown in scope and scale.

In addition to Alloy Development and Alloy Design, the real estate development and architecture arms of Alloy, over the years the Alloy umbrella has grown to also include Alloy Construction, their contracting company, and Alloy Advisory, a brokerage company. The spirit of this growth strategy is “to do whatever it takes to control the outcome,” says Della Valle. “You kind of have to be involved in everything, at least from my perspective. It’s one of the differences between the desire for ultimate quality and making great architecture and the volume and the money.” It is a process that has proven to be successful for Alloy.

Jared credits much of the success of the company to its architectural roots. Everyone at Alloy is a trained architect, and this is what gives the firm an edge on the competition, according to Della Valle. It is something that has especially helped the firm win public RFPs like their most recent project, 1 John Street. “In the public process we actually do quite well because as a team of architects we just spend so much time making the perfect presentation and using the presentation skills that we learned over the years to make a very provocative public presentation.” The architectural skillset at the foundation of Alloy is also what Jared believes gives Alloy an edge in acquiring difficult sites. “Our company tends to buy the worst best real estate. We find the things that other people can’t address because in house we can do the due diligence to solve the problem. Or we can spend the time or see something that a lot of the other development companies might not be able to.”

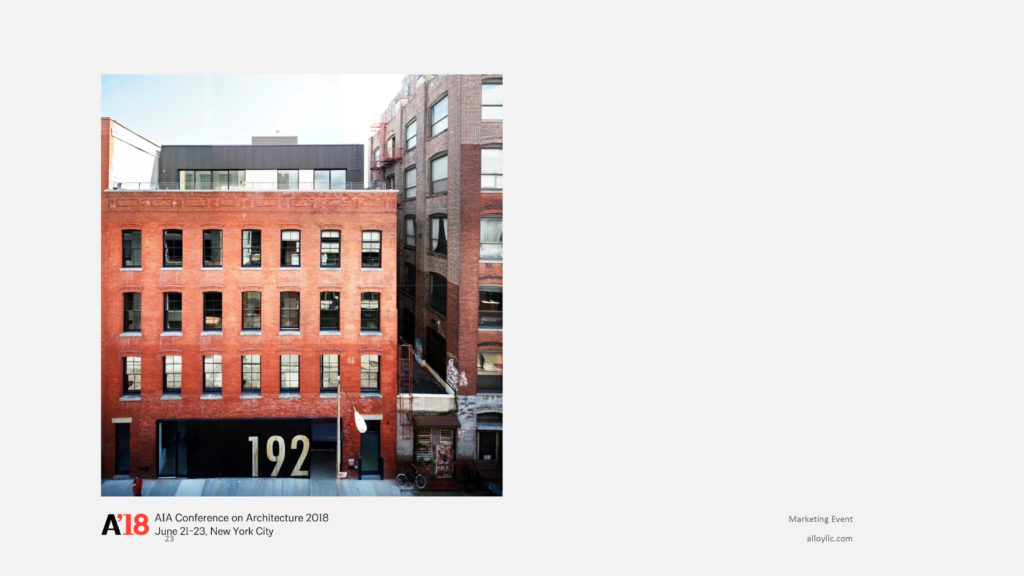

For Alloy this approach has proven lucrative. The firm’s mission, which Della Valle sums up as being “to produce great work and to leave behind great buildings,” has allowed it to consistently out-perform its competition. Average sales prices for many of Alloy’s developments have outpaced the Brooklyn average per square foot, at times by significant amounts. On 192 Water Street, for instance, the sales price per square foot was 33 percent above the average. Alloy’s projects have also sold quickly. 55 Pearl Street, for instance, a townhouse development in DUMBO, Brooklyn sold out only months into construction and did so at significant premiums, fetching between $4.1m and $4.8m per unit, well above the projected sales price of $3m per unit.

This ability to create real monetary value as an architect through careful design has long been apparent for Cary Tamarkin. The longest-practicing of the three panel participants, Tamarkin’s decision to move into real estate development came down to one issue: money. “There’s only one reason why anyone would be insane enough to be a developer instead of an architect, and that would be to make money,” says Tamarkin addressing a room full of architecture students on why he chose to pursue real estate development. “I don’t feel like a pig saying that because I devoted my entire life up to that point to the art of architecture,” he continues. Tamarkin attended Harvard’s GSD to study architecture and began a successful architecture practice with a partner immediately following graduation. For him, it seemed almost destined that he would become an architect. “Like most of you,” Cary continues, “I’ve been an architect since age 10.” After practicing for a number of years, however, the zeal began to fade. “I was having a really good time doing architecture,” he says, but the issue of compensation loomed large. “I was thinking about it for like 10 years. How do I make some money?”

“I got to the point where I convinced myself to throw it all up in the air. I thought ‘what can I do that at least has the chance of making some money?’ because I know architecture doesn’t. I was ready to give up the title of Architect even though my whole life had been about that.” Luckily for him, he didn’t have to. After considering going into advertising or set design, Tamarkin settled on becoming a real estate developer.

Cary founded Tamarkin Co. in 1994 to combine his passion for the art of architecture with the business of real estate development. He began his first project on the tail end of a recession by purchasing and renovating 140 Perry Street in New York’s West Village. The success of the project he attributes largely to good fortune and the right timing. “It turned out to be fantastic, but it was not genius. It was just luck. Pure luck. I didn’t even know that there were cycles in real estate.” Since that time, Cary has learned considerably more about development and Tamarkin Co. has amassed an impressive roster of projects in New York City.

The firm has created a portfolio of residential condominium buildings — ranging from conversions of historic structures to ground up development projects — that have garnered acclaim for their aesthetics and sensitivity to the urban context. Notable projects include: 495 West Street, which led the wave of new residential developments along the West Village waterfront and was the recipient of an American Institute of Architects Honor Award, 47 East 91st Street which is the first new residential building in Carnegie Hill to have been approved by the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission in over 50 years, and the recently completed 397 West 12th Street, 456 West 19th Street, and 508 West 24th Street residential developments along New York’s popular Highline Park. For Tamarkin, development has afforded him the opportunity to both make money and continue to pursue his and his team’s — mostly architects as well — passion for the art of architecture. “We just love it. Everybody in the office just loves what they do.”

For the three practitioners, deciding to bet on themselves has paid off handsomely. For them, acting as both architects and developers has allowed for a greater freedom of design and complete leadership on projects that have overall been very successful on a number of levels, both financially and architecturally. And all three attribute their architectural education as the engine that has driven their success in the development field.

“I’m a big advocate of a design education. I think a rigorous design program is going to teach you how to be a critical thinker. You gain skills and tools that you can apply to any number of things,” says Barrett. This design education has allowed the three to see value in things other developers might overlook. In the end, it is their attention to more than just the bottom line that has allowed them to outperform competitors. Architecture and real estate development, after all, are not all that different of pursuits. “If you’re an architect you are a real estate developer,” asserts Della Valle, “the difference with being a real estate developer is a willingness to take risk on a project. To make a decision to take control. But that’s it.”

“There is no secret on the other side,” continues Tamarkin, “I just think you have to be able to think like a businessperson for the amount of time that you are playing that role.” Combining these roles, however, is rare, and Cary admits as much. “There are very few people that are architects and developers. At some point I turned out to be the old man of this group in New York,” he jokes. Judging by the turnout at last fall’s discussion, however, the practice model is one that is becoming increasingly appealing to both current and future practitioners. If they are able to raise the capital and are willing to take the risks attendant with development, many architects may find that acting as their own developer could prove to be a better way to move forward.

]]>

In the Winter of 2017, Design Develop Construct (DDC) Journal spoke to Architect & Developer Alex Barrett of Barrett Design in Brooklyn, NY. They spoke about Alex’s frustrations with the typical architecture role and how he has taken more initiative in developing his own work, as well as the latest projects that Alex is working on. See more information about Barrett Design at barrettdesign.com. See more articles about Alex including my extensive interview with him {here}. See the original article ddcjournal.com.

Alex started Barrett Design in 2005 after speaking with a number of other architects who were exploring the ideas of combining real estate development and architecture. The architect as developer model was still very young compared to the number of architects developing today. “It’s still a relatively rare business model, which kind of surprises us, ” Alex adds.

What was frustrating Alex with the traditional role was the lack of agency that the architect had in the process. “Value really gets added to a property through the design work,” Barrett says. “In the traditional development

structure, where the architect is just a third-party consultant, they are not getting fairly compensated for the value they are creating.” Alex decided to take matters into his own hands and purchased a brownstone in Brooklyn to renovate. It was his first step to becoming a developer, and there was no way he was going back.

By acting as an Architect & Developer, Alex not only has full agency in his designs, he has better control. Instead of being pitted against each other, the developer and architect are working in concert to create a product faster and with less need for communication and presentations. “It makes the process of designing and developing real estate a lot more efficient,” Barrett says. “It forces us to be a lot more rigorous and a lot more disciplined because we know that whenever we draw a line that represents something that is going to get built, we have to pay for it.”

Alex argues that the dual-nature of his company allows him to create a higher caliber product than his developer competitors who hire architects independently. “We really love it and think it produces a great finished product at the end of the day,” he says. “We like that we are developers who are designers first and foremost.” Many projects in real estate seem to be a race to the bottom as developers try to cut costs to maximize profits.

When Alex is competing with these developers, his work really stands out. It allows the products he develops to sell faster and at a higher premium. “When a buyer walks into one of our projects as opposed to a comparable project by another developer that is not architect-led, they will feel something in our project that’s missing in others—a strong focus on quality design,” Alex says.

Alex has been developing an average of one project per year since starting in 2005. Most of these projects are within walking distance to each other near his office in Brooklyn. That will change soon as Alex makes his first foray into Manhattan with a six-story development at 3 East 3rd Street. “It’s in the Bowery, which has a really mixed and rich history,” Barrett says. “It’s very gritty, and has been kind of rough-and-tumble at times.” The firm

drew design inspiration from the area’s compelling past.

Alex has several other projects currently in design or construction. He recently completed 4 and 8 Downing Street in Brooklyn and scaling up to Eight St. Mark’s Place. He is also currently designing his first single-family

townhouses in the Columbia Street Waterfront District. By acting as the developer for his work, Alex is able to decide what he wants to design and how that !ts into the larger picture of his architecture studio. See more information about Barrett Design at barrettdesign.com.

See more articles about Alex including my extensive interview with him {here}.

]]>by David Sokol. Originally published in Departures, Fall 2017. Download the article here.

See more articles about Alex including my extensive interview with him {here}.

]]>

In September 2017, I sat down with Architect & Developer Alex Barrett of Barrett Design in Brooklyn, New York. See more information about Barrett Design at barrettdesign.com. See more articles about Alex {here} including a lecture at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design and the AIA Conference on Architecture.

Alex Barrett: I realized that there was something about the practice model that wasn’t fitting with me personally. I felt frustrated by the passivity of it. In the conventional practice model, we don’t get any input on program, the budget, or on the site. Those things are decided before the client walks in the door and we take that and do the best we can. For some people that is perfectly satisfying. For me, it felt limiting. So I tried to find an alternative.

That is when I went to Alex Garvin and started networking and asked anyone who was in real estate, “What do you do? What is it like? What role do you play?” I took some classes at NYU at night and learned about development. I tried to educate myself. Then I met Cary Tamarkin. I met Joe Lombardi. I looked at what they did and thought they got to do the design component, which I really liked. They were also involved in the bigger picture. They were choosing the site and the program. They were adding value, and they got to pick the value that they added. It checked a lot of boxes for me. Eventually, I found this small developer that had an office in SoHo. It was a two-person operation. They were two principals and I was their first hired professional.

James Petty: How much did you feel you knew about development before taking on a job in a developer’s office?

AB: I could speak the language. I could look at a pro forma and see how it balances. They still took a chance. They knew I was an architect. They knew I could at least do some design work. From my work at NYU, I could do a little bit of underwriting and understand a pro forma. They brought me in and taught me a little bit more. I did some in-house design work for them. I did a lot of underwriting for them for prospective projects. I could sit at a computer with a roll of trace paper next to me, and do an excel spreadsheet, and some massing diagrams. I understood NYC zoning and the Building Code. I could figure out how we could build a building the best we could. We would feed that in the pro forma. We would evaluate different massing schemes and what we think it would cost to build and the value we might get. It was a feedback loop. That is really what we do in my office today, and that was fifteen years ago.

What takes me today an hour or two might take a week for a conventional architect and developer client to produce. It was wildly inefficient. That taught me the value of the idea that an Architect & Developer could add a whole lot of value. That proved the efficiency idea for me. It also proved that I really had something to contribute here. I spent a year working for those two developers before I felt ready to prove it on my own. That is when I quit and started Barrett Design. That was 2005. It was a ton of luck that from the time I quit in February to the time I acquired my first property with investors was only six months. Part of my job working for the developers was meeting with equity investors. They were not my leads; they were my employer’s leads. But I got to sit in on those pitches and put together prospectuses. So I knew what was going into them and I had some practice with the process. So I called everyone that I knew. I don’t come from money. My parents met in art school and weren’t wealthy. So I called as many people as I could.

My father worked at art schools and non-profits his whole life. He doesn’t know much about real estate beyond what someone who had owned a couple of homes knows. He had been following my career. Like a good father, he was concerned that I might be doing something stupid. Out of interest, I would send him the prospectus that I had created. He happened to have a friend who was a developer in San Francisco. He sent my prospectus to him and said, “Will you take a look at this and make sure my son isn’t shooting himself in the foot?” He looked at it and said, “I think he has a really good prospectus here, and frankly, I will invest in this.” That is actually what happened. A couple of my father’s friends who were developers syndicated the first project. He also, most importantly, co-guaranteed my first loan.

JP: The biggest hurdle for most people on the first project is raising money for the initial costs or getting a co-guarantor.

AB: It is enormous. Today, the construction debt market is enormously tight. Even for me with twelve-years of successful projects, it’s still very difficult to secure construction financing.

JP: What kind of terms do you see today with construction lenders?

AB: It’s funny. The terms don’t get worse. The market for construction loans has always been relatively small. In 2005 through 2007, lenders got a little too crazy. Leverage went up; rates were really good. Then the crash came, and the market totally shifted towards the other direction. A funny thing happens when lender’s standards tighten; they don’t really use rates or terms to adjust the perceived risk. They actually just stop. It is almost like a switch. So I work with mortgage brokers. In 2016, we went out for an acquisition loan and they said that the pool for construction lenders right now was about ten lenders. I just recently went back for a refinance and to get into a construction loan, and they said that today it is about five lenders.

JP: What advice would you give your younger self just starting out?

AB: Risk is such a hard idea. Real estate people spend a lot of time talking about risk. It is this concept that is very abstract. The idea of a project going badly and losing money was entirely abstract. Whenever we put together a pro forma, we have a profit margin. We think the project is going to cost X to acquire, design, develop, and sell. And we estimate that the value of the completed project will be approximately 1.25X. Our goal is a 25 percent profit margin – those are our underwriting standards.

There is a reason that we go into a project with a profit margin. That is the cushion that you have to have to adjust. There are a lot of developers who had to make hard choices. Some people feel like they are giving something away when they start thinning out the margin. The truth is if they don’t do it, they may end up losing a lot more in the long run. We tried to take from that the idea that the market is out of our control and is always telling us something. We just have to make sure we are listening to it. The market is the market and you cannot control that. It is always telling you something.

AB: I think that architects in that traditional model are taking on an enormous amount of risk, but they just aren’t getting paid for it. We actually take on even more risk as developer architects, but we have a lot more control, and we are being paid for the risk. Paid better. For a standard architect, the profit margin is maybe a few percentage points. Any sort of hiccup in the market or if the client suddenly decides not to pay you, and suddenly your firm is in the red. It’s a very insecure position to be in. The liability risk of possibly getting sued by a client or contractor in a climate like this, which is very litigious, is enormous. You can buy as much professional liability insurance as you can, and train your employees as much as you can on procedure. It all just adds bureaucracy to the process and creates an environment where everyone is papering every decision. Everyone is very nervous to make important decisions. It is just inherently inefficient. It gums up the process, it slows the project, and it adds to the costs. That is really inefficient, and I hate inefficiency.

For more on Alex Barrett, see the book Architect & Developer: A Guide to Self-Initiating Projects. See more articles about Alex {here}.

Be sure to check out the 2019 Architect as Developer Panel at Harvard that I spoke at {here}.

]]>