To learn more about Jason, go to his:

Website: https://boyervertical.com/#

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/jasondboyer/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/boyervertic…

]]>To see more about Drew, visit his website at: https://langarchitecture.com/

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/drew-lang…

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/langarchite…

]]>

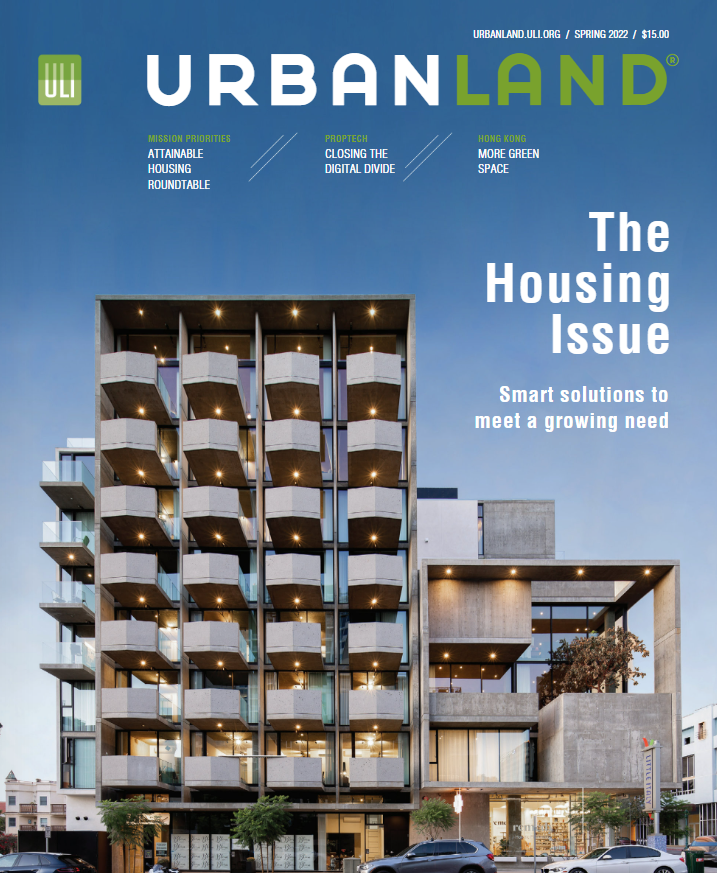

Urban Land’s Spring 2022 cover depicts a groundbreaking micro-housing project in the heart of downtown at 320 West Cedar Street in San Diego’s Little Italy. Designed, developed, owned, and managed by local architect Jonathan Segal, the 42-unit structure features 5 low-income apartments, two commercial retail spaces on the ground floor, and a distinctly separate single-family townhouse designed by Matthew, his son, that looks like a cube on the corner. And all on a 5,000-square-foot postage stamp size lot.

Like all of Segal’s projects—he now owns and rents 160 units in 5 buildings in and around San Diego—The Continental began as an experiment. This time, the architect cum developer (cum general contractor cum owner cum property manager) wanted to provide housing for people who worked downtown who didn’t have cars. The result: micro workforce houses at a price point of 65 percent of the average market rent.

The architect’s penchant for experimentation has earned him dozens of top local, state, and national accolades from groups like the American Institute of Architects for residential and urban design. In mid-2020, he was awarded Master Architect for the City of San Diego, the youngest architect at then 59 to receive the honor in a field with 5 living recipients whose average age is 91. He was also awarded California State AIA’s 2021 Maybeck Award for career design work.

Urban Land spoke with Segal about The Continental and his innovative approach to projects that push the envelope of possibilities.

What makes your firm stand out?

Segal: We don’t have any clients. We do our own work. We develop our own work. Each project that we do is sort of an experiment of what we think is pertinent to the time or germane to what is at issue at the time.

Every time we do something, it’s rooted in architecture—it’s not from development. It’s not numbers. It’s not beans. It’s not density. It is: What is right and what are we trying to investigate as an urban architectural experiment?

The Continental was created because the housing downtown was expensive and we needed to create some kind of workforce housing so people who didn’t have cars and could not pay the extra freight for a parking space could have a unit and we wouldn’t have to build an underground parking garage, which would save us money. And that was the genesis of what we wanted to do. We wanted to provide urban workforce housing.

How was this project informed by the California housing crisis and what are the chief obstacles to getting this type of affordable project done?

Segal: This was our answer to the current housing affordability crisis. It’s the law of economics; it’s supply and demand. If there’s big demand, and little supply, things get expensive. There’s a whole bunch of supply and no demand, things get real cheap.

I don’t think that the cities are allowing us to build quickly enough and easily enough and efficiently enough. They’re still getting in our way. They’re just not letting the gates open. It’s amazing to try and get something processed still. The fees are outrageous. I wish that we could work closely with cities to vet issues that would make it more efficient to process a building permit—clearly, that would be the key to the supply issue.

What inspired the design of The Continental?

Segal: We wanted to develop a project with no parking. Its façade of balconies is patterned after a Lincoln Continental car grill. So if you look at the pattern of the late ‘50s Lincoln Continentals, the grills in front of the radiators have a pattern and that was the genesis of a pattern created with the decks. Everything is car-related for me. I collect ‘50s Italian cars and ‘50s and ‘60s American cars. There is an incredible design vocabulary in these cars that I build from.

When did it come online and who is your target renter?

Segal: It was two years ago in December 2019. What we’re trying to do is we’re trying to make it for the people who actually work in Little Italy to live in Little Italy. So if you’re a bartender and you walk three blocks to work, you don’t need to pay $400 for a car payment, another $200 for license and insurance, which is $700 a month. You can apply that to your lifestyle and/or your unit. And if I can make your unit $700 or $800 less expensive a month because it doesn’t have a parking space attached to it, there’s more savings. So it’s just all-around lifestyle savings for people that can’t afford expensive downtown. The rents for 37 of the units, which are 350 square feet or less, are $1,595 to $1,995 with affordable ones at about $900 a month.

Initially, when it came online, this was an experiment. This was sketchy, risky. They didn’t immediately rent up. We had to get our market of the people without the cars in and that was a tight, small market at the time; it’s grown significantly now.

Social interaction is important in urban architecture, so we created an outdoor space at the top of the building, facing the ocean, facing the San Diego Bay. It then has its washer and dryer room connected to it so you can go up and be social, do your laundry, and then socialize with people in the building and have a fabulous view you couldn’t afford because you can only afford the unit on the second floor. So very democratic the way it enables all people to enjoy the best parts.

It is a very good product type to develop provided you don’t have to provide parking for it. And we’re seeing that all over San Diego now; we’re seeing a lot of developments. We do by example, and they copy. They’re everywhere now.

What makes your micro-housing design unique?

Segal: Besides bringing a substantial reduction in parking, we brought large individual private outdoor living spaces to indoor living. That is extremely important in a small rental and also to capture the incredible San Diego weather. And we brought an efficient layout of living space. It’s 350 square feet or less and we have a big, huge sheet of glass at the end of it so the space feels like it’s larger whereas typical developers put a four-by-four or five-by-five window at the end, this is a full-blown, huge commercial-grade window system and a nice patio that’s eight by eight.

It’s only been two years but what kind of turnover are you seeing?

Segal: Our tenants are staying. We were wondering about the units being so small if the turnover would be more than the larger complexes with the larger units and the answer is no, it’s basically the same. It’s crazy. It’s also important to remember Matthew developed a single-family residence and placed it over his Remedy Pharmacy. This living over the store row house is another typological pattern that needs to be understood in urban San Diego regardless of the unit type. We try to be a little less expensive, so we have less turnover because turnover is costly.

What are the sustainable elements of The Continental?

Segal: No parking, no cars, more transit use, more walking, more healthy lifestyle. We have nominal parking, 9 parking spaces for 40 units. And if you’re walking and your neighbor’s not because your neighbor has a car and you’re walking a mile or two a day, you’re going to be healthier. Your being healthier is going to help with your longevity. It’s going to help the medical system—it’s on and on and on. Sustainability isn’t just using bamboo floors. You know, it’s an idea, not necessarily a product. People get that confused. High density is sustainable. Urban suburban sprawl is not. I don’t care if you’re making it out of recycled building paper—your whole house—it doesn’t matter. You’re burning fossil fuels to get from here to there.

I have the most efficient mechanical electrical units that you can buy. The building is made out of concrete so the maintenance on the building is almost nothing. I’m not painting it. I’m not staining it. I’m not doing any redos. The storefront is an expensive product that lasts longer than cheap builder/developer windows. Operable windows for cross ventilation so you don’t have to run an air conditioning system if you don’t want to. We have complete solar, as much as we can fit on the roof to offset the building expenses. We don’t have batteries.

How much does the solar offset the building expenses?

Segal: It covers about 80 replace of the building itself, not the units. We just don’t have enough physical real estate area up there. We would have put more but there’s the physical square footage of the buildable solar area limited us, which is pretty typical for urban housing. You’re limited by your roof.

Do the smaller units make the math work but also mean more management?

Segal: Yes, smaller units allow us to charge less rent. And yes, you’re going to have a couple more units of turnover just by the mere fact that a percentage on a higher number is going to equate to more move-outs. So it is more labor-intensive or management intensive to manage smaller units. Without a doubt, there’s no question.

Does it have any green certifications such as LEED?

Segal: We don’t believe in that. We’d rather spend the money on the building making it green rather than spending ten grand on some certification expert to certify that we’ve done what we’re supposed to do.

This is also a mixed-use project…

Segal: We have two retail spaces. Matthew actually lives above the store like my wife and I have done since 1989. He has a holistic pharmacy called Remedy with his wife and they’re raising their first child there, Oliver.

You mentioned another rowhouse development where you created fee simple ownership over 30 years ago…

Segal: I was trying to get a fee homeownership to downtown and I cut a 15,000 square foot property into 15-foot-wide lots. And then I created something I call ‘convertible housing.’ I’m going to give you the opportunity to have sort of an extra flex space that you can either have your home office in or you could rent out as a separate unit. And if you bought one of the homes that also came with a granny flat, there would be an additional commercial space under your row house. Physically you had your business below and your home above, no commute required. And you can also rent out those spaces for income. So if you get the down payment from your parents, effectively you can live out of it for free. And that was my first foray into developing fee simple living at home and working at home. That was ‘98 and we called the project Kettner Row.

How do you replicate the best of The Continental in other projects?

Segal: We are now starting to incorporate micro-units as part of our product types. So the building next door, the high-rise—25 replace of the units are 350 square feet.

What’s your next project?

Segal: It’s a high-rise that we’re currently getting ready to build next door to The Continental. And because we own contiguous properties next to each other, we are able to for a maximum building height basement of the Continental property and this basement allows us to have a glass wall on the property lines that we wouldn’t be able to otherwise have.

We bought a 50-by-100-foot lot and we developed a 73-unit, 23-story tower there on it. We have an automated parking system that goes with that, which is kind of a first of its kind in San Diego. Typically, a downtown building has got maybe six levels below grade of parking. So you drive into a hole and you spiral down six floors to a space that has bad air and maybe encounter unsavory people without any security.

Our system basically takes half the area of a conventional garage. Your car rolls into this little vestibule parking, and you get out and the machine comes and takes it away. And then it puts it on an elevator, and it stacks it on the eight-story parking area against the building where we don’t have windows. And we’re doing it on a non-buildable lot—50 by 100—in downtown San Diego, so there’s an experiment. There’s a demonstration. No one’s done it. So there’s an opportunity.

Where does the project stand now?

Segal: We hope to break ground in September. We’re in the final process of getting our entitlements and our building permits. The cost of the building is around $31 million construction costs for 73 apartments. We’re giving away eight units to the city of San Diego free of charge for affordable housing. So the city doesn’t have to put a dime out and they’re getting these subsidized units that are about 35 percent on the dollar for rent so if it’s a $3,000 unit, it’s $1,000. If it’s a $4,000 unit, it’s $1,300. It creates a pretty good deal for everybody.

See more about Jonathan Segal {here}.

]]>Monograph has a series of great webinars on professional practice that you should check out if you’re interested in pushing the boundaries of professional practice. See more of their webinars at monograph.com.

“Unfortunately most developers are focused on the bottom line. The unfortunate thing about architects is that they care deeply about the design but rarely have the opportunity to exercise that. When you’re under one roof, you get a developer who is more focused and more thoughtful on the design.” – Alexandra Militano

]]>

In summer 2019, I spoke with Architect & Developer Michael Kirchmann of GDSNY from New York, NY. See more information about GDSNY at gdsny.com. See more articles about Michael {here}.

Michael Kirchmann: My father was a contractor and real estate developer and my mother was an interior designer – so I grew up surrounded by art, architecture, design and real estate.. Growing up I spent a lot of time on building sites and in my father’s office. During summer holidays I would work in the offices of one of the architects he was employing. This was back when we did things the old-fashioned way with yellow tracing film and ammonia prints. But it gave me the bug. In South Africa, you go directly from high school to architecture school. What I like about the American system is that you do more general undergraduate studies, and then you specialize, whereas in South Africa, it is a seven-year architecture program with a narrow focus. You can’t steer too far from that particular course. When I was at the University of Cape Town, I already had an interest in development. You weren’t supposed to veer from the architectural program, but I actually completed a certificate in real estate development.

Right after graduating, I left South Africa for New York City. I had wanted to become a real estate developer but ended up getting a job offer from Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, and ended up spending more than 10 years there. That was a very interesting and fortuitous route. Shortly after I started at SOM, David Childs and Roger Duffy came to me. We had this great client in the 1990s who was taking the class A specification that he was building in New York and adapting that sophistication and that approach to Europe. His name was Howard Ronson. He was one of the biggest developers in New York City at the time. So off I go as a young architect to Paris. Howard, Roger Duffy, AlanRudikoff, and I sitting around the table and planning office developments in Europe. Over the course of the next ten years we built 23 class A office buildings, all around 700,000 to a million square feet each, in the UK, France, and Germany.

It was during this time that I realized that I had a penchant for development. Even though I was the architect at the table, I always had a genetic predisposition to both design and development. I very quickly was able to adapt to Howard’s language and was super interested from day one in the development side. Howard was a wealth of knowledge. Eventually, that table of four people grew into about 40 people. This relationship with Howard was really formative for me – that experience of working for SOM and working directly with a client of his caliber and also getting to work with the best consultants in the world was the best education.

MK: And so then in 2007, I woke up one day and thought about how I had worked for SOM for ten years and I was supposed to come over [to the United States] to become a real estate developer. Coincidentally at that time, somebody from NYU had invited me to present some lectures in their real estate masters program, which I really enjoyed. I saw the rest of the curriculum for the course and it had a lot to do with finance, which I was very interested in.

As much as we as architects love to convince ourselves that design plays a pivotal role in development, the reality is that development is a finance game. That’s why so many people in banking get into real estate development. You have some secret weapons if you come from the design side. But the truth of moving from architecture to development is that this is a finance game. First and foremost, it’s about debt, structure in a capital stack, the waterfall, where and how you make those returns, all that kind of stuff is paramount to even getting to the point of putting design pen to the page.

So, I saw what the students were doing at NYU and I said, “I need to do this too.” I was still teaching but became a student too. I finished my Masters in Real Estate in 2008, and by then I had started the company, GDSNY. At the same time, I had done some lectures at Harvard and the Architectural Association in London, and around 2010 I got an invitation from Columbia to teach in their Master of Science in Real Estate program. Columbia is a very special place; the campus is just so perfect and the architecture school so impressive. I taught with Chris Cooper, who is now a partner at SOM. Chris and I ended up actually teaching that program for five years. That was a really fun thing where we were able to teach design within the development capsule.

James Petty: I feel like academia is a great pathway to starting a business and offsetting some of your own life expenses. I know there have been a number of prominent firms where the founders spent a bit of time teaching in those early years when money was tight. It helps ease the transition of being an employee of a firm to your own independence.

MK: Yeah, but it was also a way to surround yourself with an interesting and active bunch of people. The faculty were great and it was a great environment to exchange ideas and discussions.

So in 2007, we started the company with the intended purpose of being a developer. From the tail end of 2007 and going into 2008, we started looking for development deals. It didn’t take us very long to realize that 2008 was not the best time to be in development. One of the things I did when I left SOM was to make a commitment to myself to not poach any SOM clients. At the same time, there were some new relationships that I built that led to new projects, such as the Bahrain International Airport and 540 W28th Street. So luckily, we were able to fall back on to our original core competency, which is design. From 2008 to 2010, we actually ran a very successful architecture firm. We opened up an office in London and did a couple of towers in London, and a lot of really good stuff in the Middle East. For all intents and purposes, it was a good business, which we still keep today. We still have the architecture business.

JP: Where you work as an architect for a client?

MK: Yeah. We don’t do it much anymore, but we do have a few legacy clients whom we love. A good example of that is our low-income housing guys, L+M Development. Being involved in these projects is very important to me, because otherwise, we’re doing a lot of high-end condos and high-end boutique office buildings. It’s just a great counterpoint for us. We’ve designed and built around 4,000 affordable housing units.

We designed a project called Arverne View in the Far Rockaways. L+M closed the day after Hurricane Sandy. That project is on the beach and it was just destroyed, but they signed it anyway. We produced drawings very quickly, as time was very short and construction had to start almost immediately. It was remarkable to see how quickly and powerfully their company can operate. From there, we’ve done probably a dozen buildings with them. It has been a great relationship.

MK: Jump forward to where we are now. If you look through our work, we also like to have fun with design. We’re big automotive junkies, so we like to do some sort of car or motorcycle project from time to time. We like to do industrial design projects. We’ve done skateboards and surfboards. We’ve done some very big art pieces in New York and in London. This is where being trained as an architect and having an interest in design really influences the development work. We’re trying to overlap this idea that as designers, our developments are also influenced by a certain lifestyle. When you are a tenant or a purchaser of one of our properties, you become part of that design ethos. It brings a level of cool and keeps the interest high.

We learn a lot of things from doing smaller design projects. For example, we just completed designing and building a custom Land Rover Defender 90. We spent a lot of time customizing the seats with different types of stitching, and now those stitch patterns are appearing in our lobbies and VIP areas. We recently did a mini-documentary about the recent concrete pour at 1245 Broadway. Exploring all these mediums just makes the job fun as well.

JP: Absolutely.

MK: That’s why when you look at our website, you might wonder what we’re doing with art and design. We really are first and foremost design-led developers. That is what we hope differentiates us from the others who are out there in the industry. We aren’t the only ones though; there are others clearly led by design, such as Alloy, Cary Tamarkin, DDG.

JP: Those are some of the larger players doing big work now in New York. Did you say that you started GDSNY as a development company?

MK: Yes.

JP: When you decided to start your own company, was it supposed to be a design-led development company?

MK: Always. Going back to the Howard Ronson days, we were participating by putting our design ideas on the table. He was participating by putting his development ideas on the table. I’m pretty sure he didn’t learn much from us. He already knew everything. But we learned a lot.

JP: That is a great opportunity.

MK: So going back to that table that we used to sit around in the 1990’s in Howard’s apartment. The other guy that was sitting next to Howard on his right-hand side was a guy named Alan Rudikoff.

JP: Who is now your partner.

MK: Yes. Alan was the guy who did all the finance and structuring. He did debt structuring, equity structuring, all of the financial modeling, that whole side of the business. He and I were the same age and over the course of many years, we kept in contact. He is a very successful developer and we just kept working together. In 2012, he moved back to the US from Sweden where he was living and working. He wanted to be back in New York. We thought this was the opportunity that we had been talking about for the previous 10 years and decided to do it.

By then I had already completed and sold 177 Franklin Street, our first office development in NYC. So Alan came over and we started looking at different platforms and various asset types. The project at 25-27 Mercer Street was the first one set up on this new platform that we started together.

JP: Those are condos, right?

MK: Yes. It was a great project for us.

JP: Is that when GDSNY took off?

MK: That put us into second gear. What kicked us off was 177 Franklin. 25 Mercer sold very well.

JP: Do you have your own in-house brokerage?

MK: No. I know some of the other companies do brokerage.

JP: I know DDG and Alloy do. I think most people are timid to do their own brokerage.

MK: We don’t do our own construction either. We hire general contractors. I just think that you have to know your own strengths and interests and there are aspects of this business that are better suited for someone else.

JP: I think a lot of architects see the broker’s fees and start to make assumptions about how little work is involved in that fee. They feel they are already making better marketing materials and selling the building to a client, why not try and sell it on the market and make those fees? I think when a lot of them actually get into it, they realize it actually is a real job that requires a lot of effort.

MK: We work with the best brokers and have great relationships. They have the infrastructure and the connections. They can pick up the phone and connect to real buyers. I think it’s futile to try and compete with that. It’s not about the marketing materials, as much as it is about buyer and leasing connections.

JP: What about acquisitions? How do you go about finding properties?

MK: We have an acquisition team in-house. They approach owners directly. We also have a great relationship with brokerage houses in the city. Our in-house team looks at nearly 200 properties per year.

JP: So they are constantly vetting through properties and looking for opportunities?

MK: Yes. If we are looking at 200 properties per year, we may be signing on two. It’s a hard slog. What is nice about it is that we keep a very careful database of all the properties. So very often we will look again at a project we looked at 10 years prior. We can go back and look up the drawings, photographs and pro formas. We keep everything well categorized. Our database has become very valuable to us because of that.

JP: It seems like a lot of the bigger actors in development around New York City are creating their own databases and sometimes even their own software explicitly for acquisition. It is one of the most important aspects of development. A lot of the money is made in the buy.

MK: All of it.

JP: If you fuck up there, there is really no way out.

MK: Exactly.

JP: With 1245 Broadway, why did you hire SOM to be the architect? Was it capacity within GDSNY?

MK: There were several reasons. SOM is one of the leading commercial architecture firms in the world. There’s a cachet to be coopted and cleverly incorporated into the projects. A part of it is my relationship with the firm. It is very strong and something that I value. You want to work with brilliant people, but you also want to work with people that you want to work with. On the investment side, sometimes it is actually easier to take a step to the side, and keep an arm’s length transaction by getting a third-party architect. That way there is no question who is the developer. A bank might say, “you’re getting a fee on this, and you’re getting a fee on that. Are you getting too much fee?” It does make things a lot cleaner from the structuring standpoint to have a separate architect. As we have grown, I still personally get very involved with the design. At this point, there are only so many hours in the day. I am still very involved in the decisions. It is always a close collaboration.

We are doing 1245 Broadway, 322 7th Avenue, aka 28&7, and we’re also now doing 118 10th Avenue. We just bought the Park Restaurant on 10th Avenue. We’re kind of between the Highline, the new Heatherwick project, and the Bjarke Ingels Project. Our project there is going to be really exciting. We’re in design right now. All total, we are building around a million square feet right now.

JP: With that amount of area you really need another firm that can take these on and produce the drawings.

MK: Especially in New York City where there are so many agencies involved. That is another reason we work with other architects as well.

JP: But you still want to continue designing?

MK: Oh yeah. We still continue to design. We just completed Dogpound LA, a gym project out there. We have a new car design coming out as well. We are still working with L+M Development and doing a few affordable and mixed-income projects with them. We are the design architects on our development at 500 W25th Street.

JP: That one is well under construction, right?

MK: Yes, it is almost completed. We have a model apartment that is opening at the end of October. It is going to be a beautiful project.

JP: I can only imagine some of their employees thinking, “I have to work for an architect now?” That sounds scary.

MK: One of the constant struggles with being an architect and a developer is that you want to make great buildings, but you have to constantly fight with the budget.

JP: There is a very real financial restraint that you actually have a position in.

MK: It is a lot like having two angels on your shoulder. “Just do the cantilever!” “Forget about those columns!”

JP: It’s easy.

MK: Ha!

JP: How does GDSNY finance the projects under development? Is it through private investment, bank loans, a mix?

MK: Some projects have a more traditional structure where we have equity and bring in some LP’s [Limited Partners] and then get bank debt.

JP: A construction loan?

MK: Exactly. Typically, you have a GP [Genereal Partner], LP, and debt.

JP: Are you always on the lookout for new partners either for current or future projects?

MK: We’re always looking for good partners. Having great partners is paramount to a successful development. It is kind of similar to when you are an architect, the most important thing you can have is a good client. As a developer, the most important thing you can have is a great capital stack. The reason I say capital stack is because debt falls into a certain category. You can have great debt providers, and you can have not so great debt providers.

JP: Are all of your residential projects condos that you sell, or have you developed rental units to hold for passive income?

MK: We have one for-sale condo project currently, which is 500 W25th Street. All of our other current projects are commercial office buildings that we will keep long term.

JP: That is definitely different than what most Architect & Developers are working on. Most of the others seem to focus strictly on residential development. You seem a lot more comfortable doing both.

MK: Sure. Both my and Alan’s experience has been predominantly commercial office. We have done some residential. I think there is definitely a healthy balance between residential and office. It is a good diversification. It is not that easy to do, because generally, architects and developers specialize in one or the other.

JP: How do you fund the architecture side of your business? These costs are generally seen upfront before you can capitalize on the development. Are you taking fees from financing or cash flowing this as you go along?

MK: Before or after we sign a deal?

JP: Before.

MK: Well basically that is our underwriting costs. We have to bear those costs ourselves. We hope to make up those costs. I was talking earlier about the 200 deals where we sign two. Factored into those calculations is the money that we need to try and recoup on the other 198. That is part of the risk that we take on as an underwriter.

JP: Some Architects & Developers will factor in their architecture fee to fund the practice. Others will use that as an equity position in a deal.

MK: It depends on who your debt provider is. Some have a problem with it but most of them don’t. As far as they’re concerned, it is a project cost. Whether you’re doing the architecture or somebody else is doing it, it is a consultant cost that needs to be paid. Somebody has to do that work.

JP: You mentioned that you have found some financial institutions start to question your business model of being the architect for your own developments.

MK: It wasn’t an issue on 500 W25th Street as we paid our own architectural costs. Generally speaking, you would include that as part of a deal. Let’s say something goes wrong and the bank has to foreclose on the property. There still needs to be some kind of budget in there for another architect to come in and complete the project.

JP: Do you feel like a business background or education is necessary for developing as an architect? Do you feel like a degree or certificate is beneficial?

MK: Yes. University provides you a vocabulary. It doesn’t really provide you with experience. When you come out of your studies, you come out with a vocabulary that enables you to conduct a serious conversation in your field. From there you can learn the craft. That is kind of a long way of saying you’re definitely going to save yourself a lot of time by giving yourself an intensified course at a college of some sort. But it’s not an absolute prerequisite. If you are able to get a job at a development company with whatever qualifications you have, you can definitely get back into that role. Chances are that as an architect, those entry points are in the management side. A lot of the time, depending on the size of the firm, that project management side will be somewhat divorced from the financial side.

JP: I have a lot of friends that were educated as an architect and went to work for a development company. Many of them are not exactly doing what they were hoping they might be doing in their daily tasks.

MK: NYU and Columbia compete with one another. Students have asked me over the years which one they should go to. Which one is better? My answer to that is always; if you come from a design background, go to NYU. NYU has a very strong financial program. That’s what I did. If you come from a banking background, and your deficiency is design or implementation, then I would recommend you go to Columbia.

JP: You recommend that they focus on learning what they aren’t already skilled at?

MK: It is asking yourself the question, “where are my deficiencies?” and then trying to fix them.

JP: Do you think partnering with someone who has had a focus on those deficiencies is critical to a successful practice? I think about Jared Della Valle at Alloy and Peter Guthrie at DDG. They each partnered with someone who had that experience in finance where they were perhaps a little deficient.

MK: In my particular instance, are you talking about my partner Alan?

JP: Yes.

MK: What is so great about our partnership is that we are both skilled at what we do. Together we form two very strong bookends. And together that is everything we need to do this job. There are things that he can do better than me and vice versa. But there is a very strong overlap in our knowledge base. He will always have the ability to do what I do to a certain extent. Likewise, I am comfortable with the financial side also. But he has exceptional proficiency in that. Bringing these two things together in a partnership is like a marriage. Finding the right partner, whether it is in business or in life, is paramount. One very important thing that I learned from Howard Ronson is that over the course of his 40 plus year career, he was able to understand every single aspect of development. We would go from a lawyers meeting, to a bank meeting, to a MEP meeting, to a dewatering meeting. He would have complete knowledge of all these disciplines to where nobody could pull one over on him. That has been a very clear goal of mine as well, to know every aspect of development and the process. That is why I wanted to do an NYU course. I recognized my deficiency on the financial side. That was a very important step.

JP: If you could go back, is there anything that you would have done differently?

MK: I don’t think there is anything I would have done differently. I think one thing I have learned is the importance of your network of investors and your network of debt. That is a key component.

JP: It is all about relationships.

MK: I was extremely fortunate to have had the opportunity to work for SOM all those years. I was extremely fortunate to have had the opportunity to work so closely with Howard. I was extremely fortunate to partner with Alan. At every stage, there has been something formative that has happened. It is hard to have regrets when you look at it like that.

JP: How big is your office now?

MK: We are about 20 people.

JP: How many of those people are architects versus employees from other backgrounds such as business?

MK: It is probably a third architects, a third business, and a third operations.

JP: For the architects that you hire, do they have backgrounds in real estate education such as the Real Estate Development Program at GSAPP? Are the architects interested in what you are doing beyond a design level?

MK: Sure. But we love to visualize our projects. We use a lot of in-house modeling and visualization. So that takes a certain kind of skill. Obviously, experience in the field. For the most part, operating in New York is a very complicated ecosystem of city agencies, neighbors, etc. Neighbors are a big part of development.

JP: Do you have any words of wisdom for younger folks still in college or just getting out on getting to your level of what you’re doing? Obviously, there are a million paths people can take in life.

MK: This is a difficult path to take, but I think exploring multiple paths at the same time can bring you to a point that you’re naturally meant to go towards. What I mean by that is if you’re an architect that is interested in graphic design, and you’re also interested in development or whatever else… you know there’s a limited number of hours in a day. People work nine to five, they get out, go home and watch TV, or go get a drink, or do whatever. You can spend a lot of those hours doing other things. You can have three jobs at one time. It sounds like a lot of work, which it is. By running three parallel paths and basically running multiple jobs, you’re educating yourself and putting yourself in multiple environments with more people and contacts. Suddenly those things start to merge. They come together. Unfortunately, there is no shortcut. It’s hard work. That is one way. You get one shot in life. There is a time limit to your valuable years as a productive professional. In my experience, the way we get to a point where everything comes together is to run multiple interests at one time and to watch as those interests merge together into something incredible.

For more on Michael Kirchmann, see the book Architect & Developer: A Guide to Self-Initiating Projects. See more articles about GDSNY {here}.

]]>

In September 2018, I spoke with Architects & Developers Al Gore and Lance Cayko of F9 Productions from Longmont, CO. See more information about F9 at f9productions.com. Al and Lance have a fantastic podcast that goes through the daily activities of running an architectural practice and their current role as an Architect & Developer at insidethefirmpodcast.com. See more articles about F9 Productions {here}.

Al Gore: It literally started probably a year after we started the firm, which was 2009. Jonathan Segal was our inspiration. We even bought his course. I thought it was just a great way to go. Our philosophy has always been to take on more responsibility. If you take on more responsibility, you get more reward.

We started with a tiny house build. Lance and I wanted to do it. We had a great idea. We’re not going to make it like a cabin, we’re going to make it like this cool, transforming modern thing that has all glass on one side. It has a fold-down deck and a fold-down awning. So that it’s no longer tiny. It’s going to capture water, it’s going to have solar panels, it’s going to be all wood on the inside and super cool. We got that on Tiny House, Big Living.

AG: So that was step one and step two was a big fortune 500 company came and they said we want this, but we want it on steroids. Meaning we want two of them, we want them bigger, we want the audience bigger, we want a sky deck that goes on top. We want that to be on hydraulics. We want folding rails. So just craziness. So then that was kind of step two. Um, and then we’re holding, you know, we’re piling up money. Lance and I are keeping everything smaller.

Lance Cayko: Are we?!? We’re piling them money?

AG: We’re looking at a smaller pile. We’re like pushing dirt for money. I don’t know what the analogy is. We’re holding onto some money.

LC: There ya go.

AG: Keeping salaries low. Expanding the Firm. I’m teaching our system at CU, which is the University of Colorado Boulder. Then I’m getting the best students from there. Our work is expanding and then essentially we come into this position where we can actually buy land and then where we have enough people where we can do this project while also running our firm and doing other projects. That all started from the beginning too. Lance and I always had the idea that every year we’re going to do at least one fun project. Besides being fun, we don’t care if it makes money or not. A lot of times money does come back because people say, “Oh, that’s a great idea. We either want to hire you for something else or we want you to build that.” But the idea is not monetary whatsoever. It’s just this is the coolest thing we want to do right now. So that we funded all by ourselves, put it in all our own money, went alone, didn’t have really any idea of what we’re going to do with it. And it was a large, large build, but it progressed into where we are now.

LC: I think that’s the comprehensive reason why. The explanation of how we got into development, and why we’re doing development. But I’ll just cut to the brass tax. In my perspective, it honestly comes down to financial stability and making money. We are big “C” capitalists at this firm and I would say we are probably less architect and more capitalist just because of what Alex described. We’re trying to have all these various legs we can stand on. But at the end of the day, the biggest thing that stuck out to us is that if you can be the developer you get paid once. If you can be the architect, you get paid once. Then if you become the contractor, you get paid another time. So you can get paid three times to do the project. And then on top of that, you get to have control over the whole thing. For better or for worse, you know.

One of the things that we’re finding is, you know, we feel like we used to get beat up by developers all the time on fees but then also design. So you put your heart out and hold them to the design. But it’s been interesting for us to see the backside of it. I’ve just kind of been a cutthroat contractor and just having to slash things that are pretty meaningful in this project to get it under budget. At the end of the day, what it’s going to enable us to do is be better architects. We’re going to have such a better idea of how much things cost just from the beginning. Like, let’s just not even pursue X, Y, Z because we know it’s going to get cut anyway. What is the better way to approach, X, Y, Z on a project?

AG: It was so funny. We’ve done a dozen of these projects that are very similar for other developers and each time we say we’re not going to go up to the inch setback line. We’re going to give ourselves some play. Then we do our own development, and suddenly we’re up to the inch because that’s how it works out.

To put a caveat on what Lance said is that yes, we’re capital “C” capitalists, but big “A” architecture-capitalists. It’s not coming solely from the idea that we want more money. It actually comes from our birth. We were born during the recession. Lance and I were at the top of our class in architecture school. We worked at amazing, world-famous firms, and then the recession hit. It’s like, okay, we just worked hard for six years of school, two years working for these guys, did what was defined as really good work and really hard work. And then the bottom fell off. So then we realized, oh, they only have one system of making money. They had no backup plan. They didn’t have multiple legs. You don’t know this when you’re young. That is kind of where it stemmed from; getting stability. It’s a big “C,” but it’s also a big “S” for stability. We live in that world where Lance had kids and I had an apartment with nothing in it. If you are old enough that you went through that recession and you were a good worker and it did not matter, that leaves a lasting legacy.

James Petty: So you guys took the Jonathan Segal Architect as Developer course. Is that where you learned how to make pro formas? Did either of you have any other type of formal business education?

LC: Nope. We took the class and the big takeaway for us was that you can treat a building permit as cash equity. Architects always like to complain, and rightly so, that we don’t make any money. Part of it is because some of them are just too far into the art of it and less into the science and the business side of it. The other part of the reality is that you’re not making as much profit as a developer. So it’s hard for you to like get enough capital together to be able to do projects like this. That was our big learning lesson.

He [Jonathan] was able to put all of his time and effort in. Obviously, you pay your engineers and stuff like that to do a portion of it. So there is some cash equity into it. But the fact that you can take the drawings to a bank and say these are approved, this is how much they’re worth, and therefore use that as cash equity. And then do things like defer the developer fee. On a project like ours, there’s actually a line item in the pro forma that we were kind of shocked to find out. Developers put in a line item that says, “Our developer fee is 10 percent.” Well obviously there’s a lot of work that goes into being a developer, so they have to account for it in some way. Well you can go into a bank and you can defer that fee and it can count as collateral. Not all banks recognize that. You need to find a bank that recognizes that and values what you’re saying is there. The same thing with the contractor, you can defer the whole contractor fee. So all of a sudden you’re in this interesting position that you never thought you could have been in.

The pro forma side of things came from the EntreArchitect community on Facebook. They were happy to give us some pro formas and then they pointed me to this amazing website, guerrilladev.co. They had everything online. We just downloaded them. And then we just went through it and kind of did it. It’s kind of reflective of like how we run F9. At the end of the day, we just use a lot of common sense.

JP: So you were able to get the bank to recognize the architecture, developer, and contractor fees as part of your equity up front?

AG: Yeah. The key to that was that there was one bank in the area that everyone uses. I told Lance that we need to get them in here and take them into consideration. But we need to have multiple banks because some of them tried to pull a fast one at the end. You defnitely need to have multiple banks working with you. Just to choose one and lock yourself into that, I don’t think it’s the right game.

JP: Did you find your bank by talking to other developers in the area realizing that they’re all using the same people?

AG: That’s how we heard about one of them.

LC: The one that we really liked that stood out for a couple of reasons. So what they did is they basically looked at the development log. It’s public where we operate in the city of Longmont, CO. They saw that we had a plan submitted and they reached out to us. And then what kept standing out is they kept following up with us. You could tell they were interested in us and they even went to our planning and zoning meeting, which is huge. It’s literally reflective of how Alex and I run our businesses. Phone calls within 24 hours. Emailed back within 24 hours. You know, run head-on into problems and the go after people and be enthusiastic.

JP: In Episode 4 {listen here}, you mentioned that you were trying to mitigate your upfront cost by working out a deal with your engineers and consultants. You talked about the idea of trying to pay them a higher fee overall but only 20 percent pre-construction with the balance when the project sales. Basically, getting your consultants to co-invest. Did this work out? Were you able to get consultants and engineers to sort of co-invest with you?

AG: No, that didn’t work out. Some of them gave us a buddy deal and lowered their fees to normal. Some of those worked out. I would say one of them was the wrong fit. We forced a commercial person into a residential situation and we need to rectify it now. I don’t even think that what their plans gave are buildable or cost-effective. So there is a risk there. There are people that I know now on bigger projects that I would call in. They’ve done this a million times. You’re not going to get everything 100 percent right. I think that’s the lesson. People want to have all their ducks in a row before they pull the trigger. You’re literally building the bullet while you’re on the ride in the ground. That’s what you got to realize.

JP: How much money did you have to spend up front on consultants, engineers, fees, and other costs without making any money until the project is either rented or sold? For another architect that is trying to get into development, what kind of upfront capital should they be expecting to spend?

AG: Lance is doing the math.

LC: Rattle off the different items and I will add it up.

AG: MEP. Landscape. Civil. Structural. Surveyer. Surveyer plus soil. Insurance.

JP: Did you guys need to use an expeditor or have any city or permit fees?

AG: The fees are wrapped up in the loan. Expeditors are not a thing here in Colorado. But you need to budget and have your firm be afloat for how much architecture you have to put into it. If you are talking about doing a project that is bigger than a house or duplex, you are talking about a staff member being dedicated for a long time.

LC: Yep. I just kind of added up some rough numbers here. This includes all of our engineering, consultants, surveyors, everybody like that, where it ended up being cashed. It was about $75,000. So like Alex was saying, then you add architecture on top of that. Diferred architecture fees. That was probably another $175,000 worth at the market rate last year. That is where you can really prove that this is really equitable cash coming in. The other thing I was thrown on top of that is we have paid about $70,000 worth into land development. So we took out this three-year balloon loan.

AG: We put 30 percent cash down.

LC: So at the end of it, I would say hard cash ended up being about $150,000 and then on top of that it looks like deferred architecture fees are about $150,000. It looks like the total amount of what we’re saying is our equity in the project is between $300,000 and $400,000 to bring to the table and get the deal done in this very unique way.

JP: The land loan is something that’s very unique. You guys took out a three-year land loan, but that was quite a while ago. How is the land loan working out now with the standard timeline of development along with all of the delays with the city?

AG: We still have some time on it. The land loan will transfer over into the construction loan.

JP: Does that transfer happen once construction is complete with the take-out loan for the construction loan, or does the land loan get transferred into the construction loan once construction starts?

AG: Once it starts.

JP: So all you have to do is get into the ground within the three-year period?

AG: Yup.

JP: What is happening with all the entitlements on this project? Does every project within Longmont need to go into the city for special approval?

AG: Anything over a house has to go through the site plan review. And what’s crazy about this, if you boil it down to simply pages that you’re turning in, there’s a lot of work done for every page. The site plan review is basically 20 pages, maybe 25 of architectural, civil, landscape, and a couple MEP. Now the architectural plans with full on everything is about 85 pages. It took over a year and a half to get approval for site plan review and we will still had as many consultants for a building permit. But that building permit took two months.

JP: It feels like for the first project you would almost want to try and avoid something like that. Just to mitigate the risk. Have it all done faster and just get the project out from underneath you.

AG: Exactly. Move to rural Iowa and they won’t care.

LC: It’s such a double-edged sword. Because of all these regulations and the terrible process, it makes it so that the housing stock is very slim. If you can build something, if you get it through this process, you have a product that is so highly sought after that you can make money on it right away. Whereas if you go to someplace like Iowa, North Dakota, or whatever where it is very lax, you can just get something through. We got a gas station in North Dakota through in under two weeks. It’s a gas station. You’re talking about EPA flammable stuff. Still in two weeks up in North Dakota. But you can’t. The market up there is terrible to sell stuff. It is what it is.

So yeah, it’s a risk to take on a project like this and navigate it through such a cumbersome system. But we had cut our teeth enough on other projects in other cities enough that we knew we could take a little risk here and even though we’re not through site plan development, we can submit building plans to try to compress time a little bit. We were able to do that. If we end up with a building permit right now, we’re talking on September 07, which we think we’re going to be able to by

September 17th, we’re only 17 days behind where we wanted to be. I mean we obviously want to be building as soon as possible, but I think we did a pretty good job at compressing time by doing those kinds of things.

JP: Lance, you got your class B contractor license to be the GC for the development project. Did you require that license for the project in Colorado?

LC: Yeah, it comes down again to equity, right? With that, we are able to say to the bank that we’re going to defer 70 percent of that fee. So that is hundreds of thousands of dollars that we don’t have to finance. That’s really the leverage point with that whole thing. And then also be able to be in control of the whole project is critical. So it wasn’t a requirement actually. Nobody required it other than ourselves. I think it was a requirement that we recognized we needed to meet order to get this financing done.

JP: Right. I’ve heard that being a licensed contractor can also help you with your insurance premiums. Was that the case for you guys in Colorado?

AG: I think with typical residential it might. We had to do condos and condo insurance is insanely expensive. We also had to get Wrap insurance. This is what was so hard dealing with the city. They even wanted to change rules on the pathway as we were talking to the mayor and to the city council. One of the best pieces of advice is if you’re starting any project that is bigger than a house or duplex, you have to start meeting with these people earlier and establish relationships. They don’t honestly understand the ramifications of their laws. They were trying to do affordable housing that would apply to us. They said that it won’t really affect our project. They thought we could sell them for a specifc amount. Technically, we’re condos. We can’t sell them for that much based off of their affordable housing standards and prices. “So why are they condos?” Their zoning code won’t allow us to lot split like in Denver. It’s crazy explaining to them that Denver, which is a very very hot market, and no easy feat to get through the building and site plan review, they are more stringent and more restrictive and have more rules up here that make it cost more. They just don’t understand that. So the process.

JP: So you guys are planning to sell off the units as condos?

LC: Yep. Swinging back to Jonathan Segal and a lot of other architects. They never do condos. Then you realize the project we are developing is the same sort of scope and size as the one Jonathan did to launch everything. He ended up not doing condos after that. I think he did like three or four of them that were technically condos. At the end of the day, he said don’t do condos, but then sometimes you just got to do condos to get yourself going. He says to get as much insurance as you can. Whatever the maximum you can. For this project, we insured it for $2 million. We technically only needed to do $1 million, but we ended up doing $2 million. It didn’t escalate the cost too much for the insurance premium. So that’s all you can do.

The Warp insurance has been actually pretty enlightening. They bring in a third party inspector so our eyes are going to be on it the whole time. The third-party inspector comes in and they make sure that that construction is done the way they are anticipating. It seems like a pretty foolproof way. You can even save a little money from your subcontractors. You can say, “Hey, I’ve got this Wrap insurance policy, therefore you guys don’t technically need as much insurance because I’ve got you covered.” Then you can reduce their fees directly and save some money.

JP: I think that is one of the most concerning part of creating a condo. You have potentially one big roof. If it starts to leak, you have six different lawsuits to fight off. You know there are all of these attorneys who basically just go after insurance money.

AG: Yeah. So our solution to that is that it’s a mixed-use project and one of the units is our office. If there’s a problem, if there are things going wrong, we’re not going to be blind to it. We’re going to quickly respond and communicate, which is what I think the problem with most developers. They’re slower to communicate and people get frustrated, things don’t happen. Right? It turns into a disaster. So that’s what we’re not doing.

JP: Is one of the reasons you guys wanted to do a mixed-use development to get a free office space out of the deal?

AG: There will be a monthly payment on it, but it will be in line with what we’re paying now. Except we will own it.

LC: That’s part of it, trying to be lean and mean. We’re taking this giant risk to once again get lean and mean. And then after this project, we’ve got my eyes set on a piece of property that’s on Main Street that we’ve already had a scheme worked out with the new zoning laws and ordinances. We should be able to do higher density. So we do want to try to move into where Jonathan Segal is now. He does mixed-use projects where it’s commercial on the first level and then rental housing above. He holds onto them for two years and then sells off the whole thing. So he started doing this, and now the guy is a multimillionaire. He only does whatever he wants to do at this point. We will still always take on clients, right? But I think it just allows us more flexibility of who those clients are. We would have more leverage with what we can charge because we can turn down other stuff. That’s where we’re heading.

JP: So for this development, are you guys getting a standard construction loan of about 70 to 80 percent of construction costs?

AG: Yup. 75 percent loan.

JP: Are you using the equity from your fees and what you put in for land acquisition to help bridge that gap? Or were you guys also bringing in cash money to the table?

AG: So far, we do not have to bring in any partner other than Lance and myself.

LC: Do we have backup plans? Yeah. There are some interesting details that we won’t disclose about how things work. But I will say this, if you get out of the residential realm and you get into the commercial lending business, money can change hands a lot differently to make things work. That’s the big difference for us is that this will be a commercial loan. For the bank, it’s not a lot of money. To us it is, right? $2 million is nothing to scoff at that. That’s what it’s going to take to get this done. It’s been a learning lesson for us and they just keep saying, “Oh yeah, this is easy. We can take care of this.” Once we submit the application, they take care of it in three days as an administrative review. They see no problem with us literally building within 10 days from this conversation today, which is kind of blowing my mind.

JP: You guys mentioned in episode 27 {listen here} that you don’t necessarily recommend people with an undergraduate architecture degree going back and getting their masters degree. What about a business or real estate degree? Do you think getting an MBA on top of an architecture degree is valuable? Do you wish you had gotten an MBA?

AG: Two thoughts on this one. I haven’t got an MBA so I don’t know if my opinion is valid, right? But secondly, I got my masters in construction management. I took classes and then I did a studio portfolio, like a project, but I took it to a deeper level. I made the website. I actually made a pro forma. I talked a lot about sustainability. I designed the townhomes. I have this thesis book. I go, “holy cow.” I looked at the layout. It was three levels stacked with six units. So I was like, “Holy cow, it was kind of a prep.” The problem with school is that it’s maybe great to be aware of what to look at and what you should do, but what it’s going to come down to in the real world is to take those steps and then call the people in the industry that you know to get the right answer and what’s actually going to happen. Then you’re playing the game of do I want to pay however much it costs for a degree, $50,000 to kind of just get an overview of what’s going to go on. And then know that I’m going to have to relearn things for specific situations and consult with people. Or should I start developing those relationships now and developing that background because that’s what has actually paid off for us.

I’ve come to the conclusion is maybe it’s not worth it to pay that money to sit in an isolated tank and throw darts against the wall that doesn’t have much feedback.

JP: You’re more interested in getting into the field and going for it. Simply learning as you go along.

AG: Yup, as long as you have some sort of competency already. Someone taught you how to draw, how to design, something like that. I understand you have to have a certain level of education, but I think it’s maybe going a little bit too far. It’s just that feedback loop in the educational world is looser than the real world.

LC: I’m now at that point in my logical conclusion about higher education. How many people are educated? How many people have degrees right now? We live in Boulder County and this is the second most highly educated population in the United States county-wise. We have the most masters and PhDs per capita. My conclusion is to only go to school for the least amount of time it takes for you to satisfy licensure requirements. So if we’re going to go for a contractor, look into maybe a two-year degree. That’s it. That’s all you need to get qualified and build your resume.

Same thing with architecture school. We have a couple of guys right now in the firm that are going to go the long route in Colorado. They have a bachelor’s degree. But if they do thousands of hours of work underneath Alex and I as licensed architects, they can still get licensed in Colorado. It’s the minimum amount of time, money, and effort that you need to put in to get that license, which then enables them to do things like we’re doing.

AG: This is what’s hilarious about the hour requirements, right? I don’t know the real number, so I’m gonna make this up. If you get your master’s degree, let’s say you have to do 5,000 hours and then you can take your tests and do all that. If you don’t have a master’s degree, maybe it requires 7,000 hours. But oh, that’s two years. Master’s degree from their bachelors will take two years. So either I could do two years and pay someone or I can do two years get paid. It worked out with the same amount of time.

]]>

Jonathan Konkol and Miles Sisk at Plan Design Xplore recently interviewed Lloyd Russell about his practice as an Architect & Developer. See a portion of the interview below, and the full original interview at plandesignxplore.com.

Plan Design Xplore: We came across Creston Lofts on one of our walks around Portland neighborhoods, and we think that it’s a really excellent project for a number of reasons and we wanted to ask you about how the project came about. Can you talk about the history?

Lloyd Russell: Okay, so I’m an architect living in San Diego, from San Diego, I went to Cal Poly San Louis Obispo and spent my last year abroad in Copenhagen. When I was in college I was always questioning the role of the architect. How the architects could do more, because I was always driving back and forth from San Diego through LA to get to San Luis Obispo, and LA was like this bane on my distance, and I could never figure out why Los Angeles existed if my teachers at Cal Poly were telling me that architecture was the highest art and calling for anyone in life, and I could never answer that.

I couldn’t answer that question until I figured out that I had to ask the question of why buildings got built and that got me into the economics of building. And then I also got into building buildings, not just being an architect; I liked to go out and work with contractors to build stuff. So long story short, when I graduated I found an architect that would do design-build, and built his own stuff, and develop his own stuff and develop his own stuff and so I started working with him as an owner. So I acted as an owner, acted as a builder, an architect- developer-contractor on a handful of projects so I got to see that sort of stuff so I get to have the role of an owner the role of a contractor the local architect and then live in the building to get the role of a user.

Before I had kids, when I had all this spare time I also sat on some boards; in San Diego for the Community Redevelopment Authority, and they were talking about the zoning policies and stuff like that and so I got to see it from a legislative standpoint as well. So I turned this little equation on all sorts of different angles…

PDX: We’re interested in the architect/developer combo…

LR: [Teaching] has been consistent throughout my career, and we were always trying to teach housing. And we can never teach housing without a budget, because there are always constraints to housing, unless it’s a custom home and it’s pie in the sky, but it was always hard to convey to the students, like, some reality, and so we started to teach them a pro-forma, which is a little hard in an architecture housing studio.

Eventually evolved into starting a program that we called a masters in real estate development. That was like ten or twelve years ago and it was how to be an architect-developer, and it became a master’s program for students at Woodbury University. I think it was one of the first ones in the nation to offer the whole thing. At first, when we were doing this we thought, oh my God, we’re just gonna create competition for ourselves in San Diego, and this is gonna be terrible! But it ends up that through the sharing of information we’re not really competing against each other. It’s more of a synergy, so there’s a whole bunch of people doing like-minded buildings that are not the standard a developer building because they always have a little twist ‘cause there’s an architect in there somehow and the sharing of information helps. But down here our big battle is this building department and zoning that is just ridiculous.

When I was on the redevelopment board for the Center City, which was the Planning Department for downtown. That’s when I started to work on Creston, and I read the zoning document from Portland, and I was like Oh my god, you guys in San Diego are so myopic. You have this Byzantine zoning document that contradicts itself and nobody knows what it means and as a result nobody can build any housing and up in Portland you have this very concise, form-based zoning which is so clear to everyone that it makes it really easy to plan and develop projects, and I was trying to get [San Diego] to incorporate some of the form based on it.

PDX: Your answer anticipates one of our next questions, which is why Portland, since you’re based in San Diego.

LR: My friend Andy [Lair] was a general contractor, and we bought a piece of property together, but it was on a fault line and we had to sell it. He moved back up to Portland but we kept the conversation going and he bought a property up in Northwest [Portland]. It’s kind of an industrial property, and he asked me to check out the zoning to see if he could do anything on it. When I read the zoning I was like oh my god, you don’t want to do it there, but there’s so many great areas in the city that you know came up, and you know I visited a handful of times and I just said you find a property that sounds like XYZ, and you know we’ll do something. He had gotten his general contractor’s license at that point, and then he found something and we started to work together on it

So that’s probably what brought me up to Portland. I found it very similar to Copenhagen in the weather and in the urbanism; never really raining just, drizzly kind of thing. Everyone bought into the urbanism – here in San Diego, everyone’s complaining about how, oh my god, there’s no parking!

PDX: So to bring it back more specifically to Creston lofts. Help us understand its partí a little more…

LR: First zoning, where there was no limitation on the floor area or the density to set the form-based zoning and it was near to where Andy lives so there’s kind of a close connection to Reed College. If we have a 10,000 square foot parcel this will be a really interesting project and an that time Andy was showing me new projects around Portland because he was very concerned that we were going to do something very modernist and at that time. I think this was 2008, 2009, 2010 kind of time period. There was a big discussion about modernist versus historical stuff happening in Portland.

The design of Creston was actually kind of a critique of some of the projects that I saw at the time, where a lot of projects would just max out what they could do just because they could, and what I didn’t like was when you have the form base zoning and then it transitions into a neighborhood, and there was no transition!

It was oftentimes a big blank wall, or you know the scale wouldn’t fit. And since this was going be the first project in that intersection, I was trying to figure out a way to kind of mitigate it into the neighborhood. A campus of three buildings seemed like a more appropriate way to kind of soften the transition into the neighborhood. It also allowed me to develop deeper into the block because a full-coverage building with double-loaded corridors would not allow for cross ventilation and a lot of light, stuff like that. So I was trying to figure out a bunch of what I call single-loaded buildings where there’s not a hallway.

PDX: That’s one of the things that struck me the most about housing in Copenhagen; I don’t think you’re allowed to do double-loaded corridor buildings, so all the perimeter blocks, while they look fairly massive, aren’t very deep; they’re made up of through-units with at least two window walls.

LR: Yes, there’s a lot of projects we didn’t have the scale for but this also goes back to the developer portion where you know when you’re when you’re the developer you don’t want to build anything wasteful, I guess so what I was trying to avoid was you don’t want to build infrastructure that you can’t rent, so no elevators no, hallways or corridors, no lobbies, and when you take that out of the equation and everything you build is rentable, you might be building less density, but it’s a more effcient building.

So that was kind of the attitude; I built with lobbies, elevators, corridors, that might take up 20% of the building, and even though I have a bigger building, I have to borrow more money and It’s not as effcient so it’s not as feasible.

PDX: We’ve seen a handful of projects in Portland like Holst’s Meranti Lofts, with no elevator were you have townhome units on the upper floors so you enter on the third floor and you take an internal stair to the fourth floor your bedrooms. Is that similar to Creston?

LR: Yes. Ideally, you want everyone to not have an elevator and walk around the property because again, as a developer, I’m not paying for the maintenance of the cost elevator. But and the other hand, from an urbanist standpoint, if people are walking around the property, those are the eyes and ears on the street that make it more secure and that’s how you get to know your neighbors, and the property becomes safer and more vibrant and you build more of a community.

I’ve done buildings where there are elevators and the tenants don’t know each other from one end to the other or one floor to the other and there’s a totally different vibe of the building. I guess this gets to building types. It’s like, if you’re gonna get to the elevators and corridors it to achieve your economies of scale, then you have to really pay attention to how you break down the scale and make it more of a community.

For Creston we had a 30-foot height limit, so we’re telling pressing up against if it’s either two or three stories. You’re kind of against that limitation. I wanted to make sure that we could develop into the into the interior of the lot as well, and there’s a transition to the east where there was a building to cut it to the south where it was going back into a two-story and one-story houses, stuff like that.

PDX: I noticed you have a really large Japanese maple mid-block. I’m assuming that’s a holdover from what was on the site before.

LR: Exactly – The house had a big tree in the back and we decided to preserve it. We could we develop the property around it or we could always plant a tree, but that was such a nice tree. That’s the kind of thing you can do when you’re the designer and the owner – you can make decisions like that and then work around it. Usually, the architect gets the mantra from the developer that I need X number units no matter what and then you’re kind of screwed, so part of the architect-developer thing is the person that decides the program is the one with the power.

PDX: We’ve walked around this property and taken a lot of photos, but obviously it’s a very complex division of space. How do all the units Tetris together in there?

LR: I like very site-specific building projects. Each orientation of a building, of the units, is unique unto itself and also from owning these buildings… There’s kind of a housing experiment going on, so this is definitely for rent. I’m not doing condos because when you get condos It’s got to be the lowest common denominator. That’s very comparable to something else ‘cause someone doesn’t want to buy something that’s unique. But when you’re making rental properties, you can make a very unique floor plan and sometimes that’s what makes it rent – because it’s a one-of-a-kind unit in a city and someone’s gonna say. Oh my god, I’m the only person that has this window this giant window that pivots, or I’m the only person that has this really cool layout or something like that. So I try to imbue the units with this kind of drama. Or taking advantage of whatever orientation is and so each of the buildings is addressing that condition. The building on the east is economical townhouses, but they’re walk-up. See you walk up to three three-story building and there’s a little juice bar on the ground floor and then two studios on the ground floor, but the second and third floor you walk up, and I put the bedrooms on the second floor, so I called it upside down master – the bedrooms are on the second floor, and then you go all the way upstairs and the living room is on the top floor because that’s where the view is. So that has a certain efficiency.

PDX: So there’s an attitude toward affordability in what you want to build.

LR: My attitude towards affordability is sort of like this: you want to build it as small as you can, but you want it to appear as large as possible, and in order to appear as large as possible you want to connect it to outdoor spaces. There are myriad health benefits that come along with that as well.

Renters want bigger spaces, they want closets, they want this that or the other and it’s like well yeah, but then your rents gonna be so high… so you’re trying to… I want to give them a lot, but I want it not to cost too much, so I try to get them dramatic spaces so that usually comes into things like tall ceilings, big windows, a connection to the outdoors, stuff like that. In the corner building, we have a restaurant on the ground floor, and that was a friend from San Diego that married a friend of ours in Portland and moved. That worked out.

It has a semi-public space on the second floor, so it’s this giant deck, which has four studios off of that. It’s extra-wide – it’s over 15 feet. I can’t give you private outdoor space but I’m going to give you semi-private space, where you share it with maybe two neighbors or something like that. Also, it was taking the ground plane and saying here’s the here’s your patio, but it’s on the second floor, and then from the second floor you can go and walk up to the third-floor unit which has a big deck.

And the other building on 28th, that was that was this other fun thing that we were trying to do part of the experiment. There was an existing house, and I wanted to save the house and raise it, raise the structure and built concrete walls underneath it. We went down the road of doing that but the house was in such bad condition we had to tear it down. But the idea was always to have something that was kind of like a house up above and have live-work below.

PDX: So I’d like to understand how those spaces work… I understand that those are live work and the owners of those spaces have residential space behind them facing the courtyard with the tree, is that right?

LR: Yes, then there are two more on top – penthouse units. Yeah, so there’s two units up above, and two units down below. I think the manager has a barbershop down there.