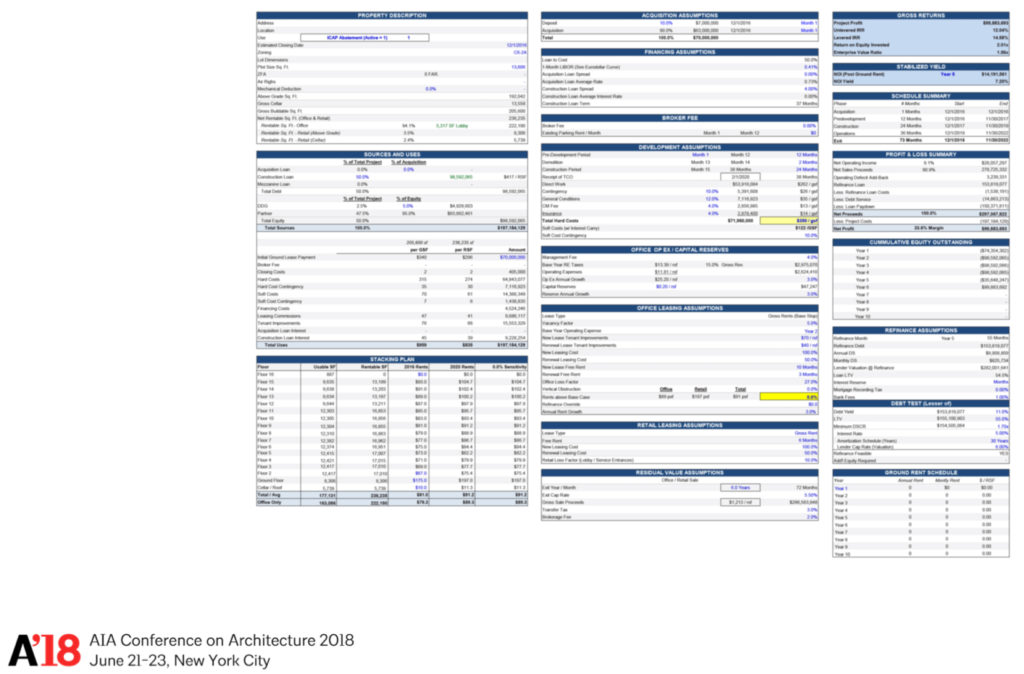

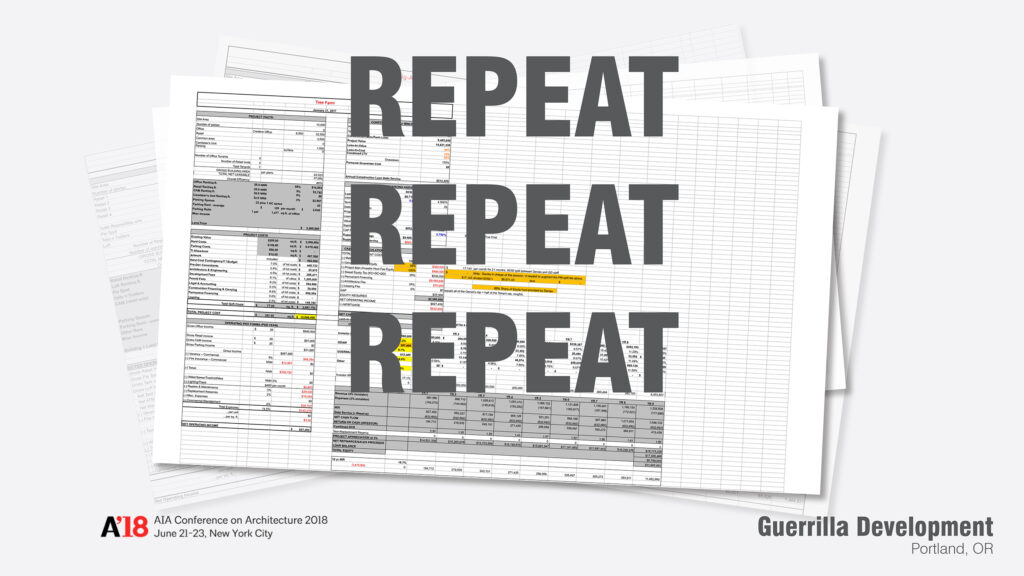

The most important tool for a developer is the pro forma. This malleable document calculates all the variables that go into putting a deal together with the intent of giving you the ability to make informed decisions regarding the project’s expected financial performance. Once created by hand, there are now plenty of software options that can be used to put these together, from the expensive and polished Argus Developer to the free and sometimes limited Google Sheets. Many developers use the same software I do, the tried-and-true Microsoft Excel. The depth of this software is phenomenal once you learn how to perform complex calculations. Architects tend to shy away from Excel, but if you want to be an Architect & Developer, you will need to spend just as much time in Excel as you do in your design software of choice. You should begin to form a love affair with Excel.

Online Course

Architect & Developer Danny Cerezo of C|S Design has created a great online tutorial of pro formas. Take a look at his videos on YouTube {here}. Also, be sure to download his example pro forma to follow along from his slack page {here}.

Example Pro Formas

There are a few Architects & Developers who have been nice enough to share their pro formas online. Kevin Cavenaugh of Guerrilla Development has a simple pro forma for most of his projects on his website. You can download them below and see more about his work on his website at guerrilladev.co.

Atomic Orchard Experiment {download pro forma}

Box + One {download pro forma}

Dr. Jim’s Still Really Nice {download pro forma}

Fair-Haired Dumbbell {download pro forma}

New New Crusher Court {download pro forma}

The Zipper {download pro forma}

Rig-A-Hut {download pro forma}

The Ocean {download pro forma}

The Shore {download pro forma}

Tree Farm {download pro forma}

Two Thirds Project {download pro forma}

Architect and Developer Zeke Freeman of Root Architecture + Developement shared his pro forma for a project he described in his Business of Architecture interview which included a 203(k) loan. See his interviews {here} to follow along.

Root Architecture + Development {download pro forma}

John Anderson posted an example pro forma on the Neighborhood Development Facebook group. See more information and download the pro forma {here}.

]]>Architect & Developer: Self Initiating Your Work

My name is James Petty. I am here with Alex Barrett, Jared Della Valle, and Peter Guthrie of Barrett Design, Alloy, and DDG respectively. I work on a website called Architect & Developer. If you guys are interested in this stuff, I am always posting new things on the website and on Instagram @architectanddeveloper.

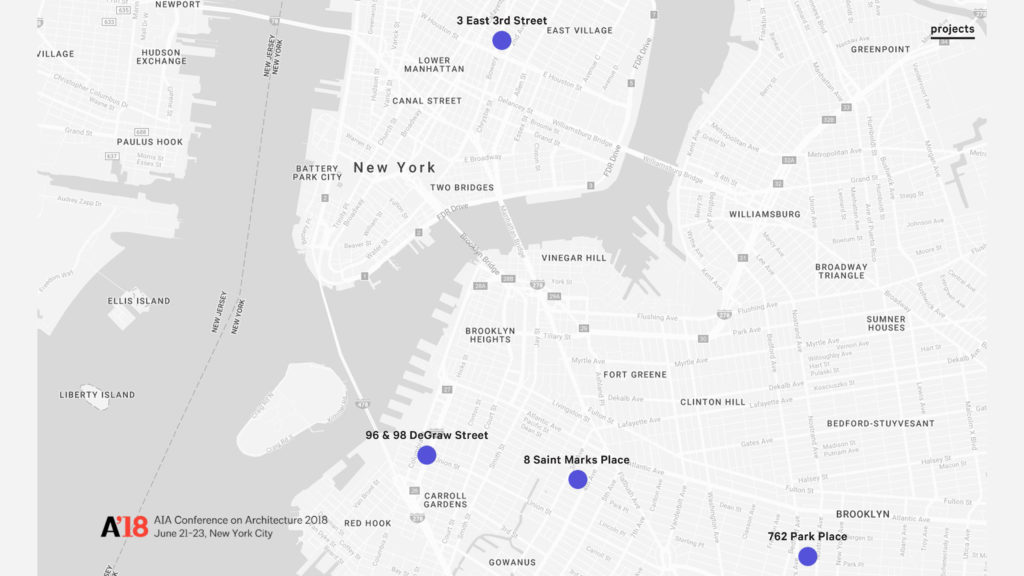

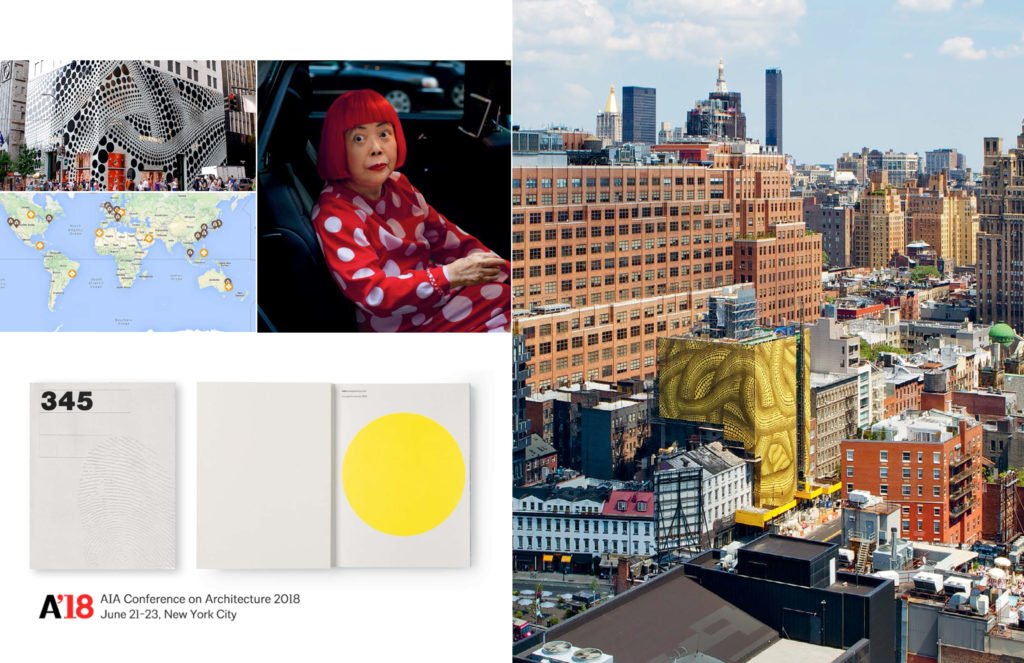

For the conference, I have put together an interactive map. Go to bit.ly/archdev from your phone browser and this will load into your Google Maps app. This will show you a lot of the projects around New York City that have been developed by architects. There are actually a lot. If you are walking down the High Line, you would be really surprised to look left and right and see projects that have been developed by these guys as well as others. On that note, let’s start with Mr. Alex Barrett.

Alex Barrett – Barrett Design

It’s a privilege to be here and especially to share the stage with Jared and Peter. Barrett Design has been around for 13 years. I started it with the premise that combining architecture and real estate development will improve both. It is our belief that designer-led real estate development is more thoughtful, more meaningful, and ultimately creates more value. At the same time, it is our belief that architects who sit in the owner’s seat are more effective, more disciplined as designers, and ultimately more profitable if all goes well. At this point, my firm is a team of seven. We have six architects and an office manager. We approach each of our projects as designers first. We seek to create the best buildings that we can within the many constraints that we are faced with, but also guided by a core set of values.

To date, we have finished eleven speculative development projects. Mostly in Brooklyn, but we just started one in Manhattan. We have four projects under construction at the moment ranging to as few as two-units to as many as twenty-three units.

James asked us to speak a little bit about how we structure our projects. Our project structure, at least from a capital standpoint has been pretty consistent over the past 13 years. We identify a project that has some sort of untapped and uncreative value that we can create through design. We raise equity from investors. At this point, all of our equity is raised from individual investors. We haven’t used institutional equity which I believe is a departure from my fellow panelists. We raise debt from construction lenders as well, and I think James will talk a little more about that kind of typical capital stack. The process of finding projects is the hardest thing for us. I wish I had a good answer for how we do it, but it’s really by hook and by crook. Brokers are involved in a lot of transactions.

Most of our projects have been condominiums, but this is a departure for us. This is two single-family townhomes in the Columbia waterfront district in Brooklyn. Our first project in Manhattan is about a third of the way through construction right now. It’s just off the intersection of East Third Street and Bowery. Not far from here [The New School]. It will be a six-unit condominium at about 20,000 square feet with retail space on the ground floor.

Jared Della Valle – Alloy

Good morning everyone. I’m Jared Della Valle, the CEO of Alloy. Alloy is a real estate development company. Twelve years ago, I had to say that I quit architecture. It required a little bit of therapy to go there after growing up and going to architecture school and always imagining that was the outcome. I felt like when I said I was an architect doing development, people didn’t understand what that meant. They thought it was the lite version. When I said I was a developer, people understood it, but people thought that I was evil and that I had genuinely quit and didn’t care. So it was a confusing dilemma that we face. An identity crisis is what we call it. We’re sort of like a platypus.

Alloy is a real estate development company. It was funny watching Alex’s slides. I feel like each of us could give each other’s lecture, certainly the beginning part. We distort the use of the word “value” in our practice. As architects, we grow up. We all feel the social contract, the moral obligations, the production of great work in our city, and we believe that architects as developers can make better choices. We can distort the use of the word “value.” In our practice, value is not about economics, it is about great architecture first.Our company is very strange. We are actually six companies. I shutter to show our corporate tree. I thought about it for a minute. I thought that this is the AIA, and that they may not like it. We are a development company, that is the holding company. We have a design, LLP. We have a real estate brokerage company. We have a construction company. We have a management company. And we have a community development company. We kind of do whatever it takes. We joke, “OK, Alloy TV/VCR Repair.” Typically we find that we can solve the problems better than the industry can.

So this came early on in my career where I recognized that developers need us early on in the process and they need us until the end. But we extract very little value from the time commitment and the from the value creation over time. Perhaps acquisition and project conceptualization, the development of program, might not come from the architect. Sometimes it does. Ultimately, the management doesn’t. But we still get the phone calls, don’t we? In the end when something goes wrong and it’s two years later. And we answer. We get nothing for it.

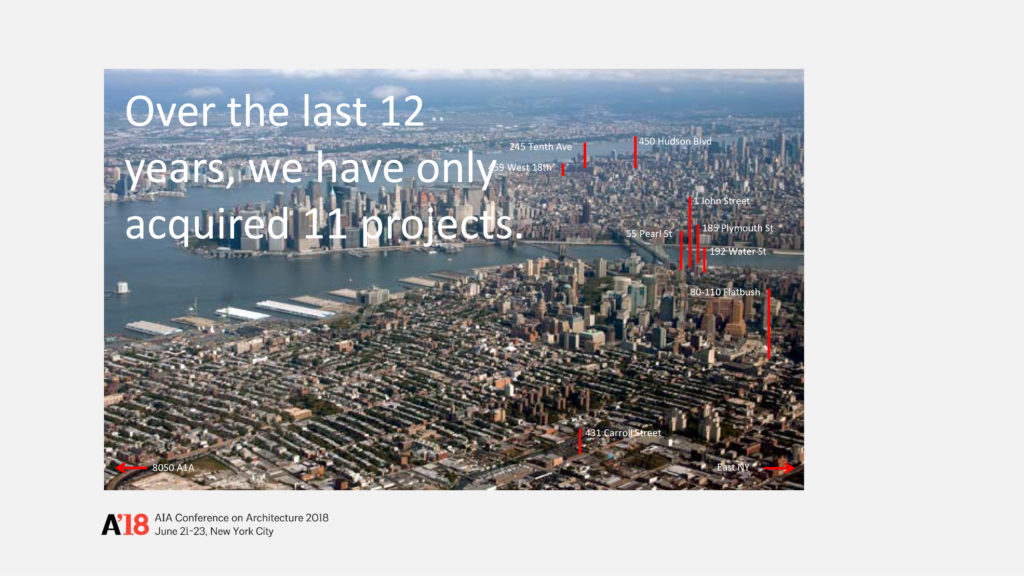

So over the last twelve years, we too have only acquired eleven projects. You’re starting to see a theme here. We only work on one thing at a time. We have no clients. We work for no one other than ourselves. We provide no services other than to ourselves. It keeps you focused on what it is that we are doing and how to manage time and prioritize the development process. Right now only one project is active. As of the other day, we acquired another one. It is sort of rare. We think about our work a little bit differently. Our office certainly functions differently. I will get into that a little bit.

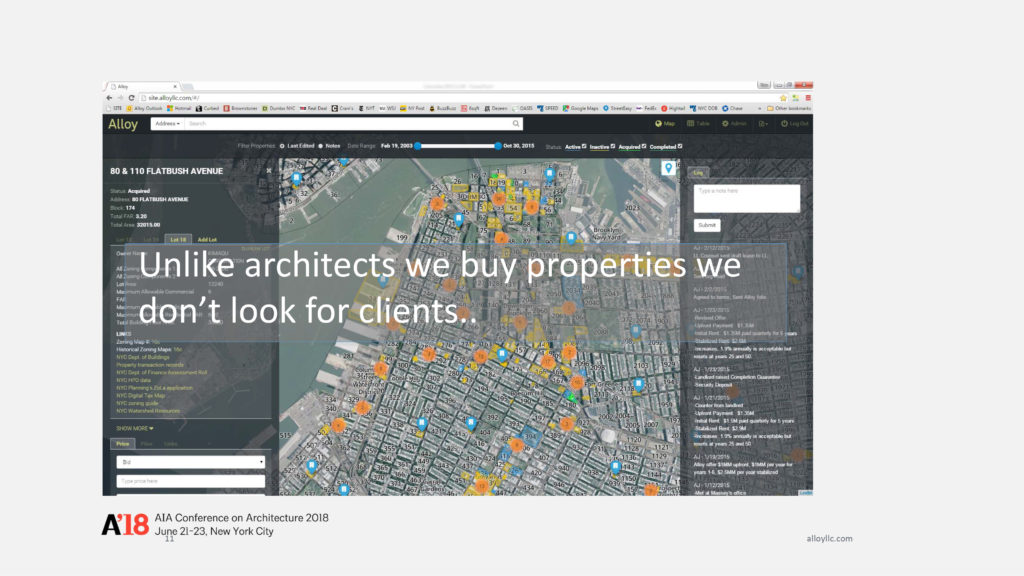

Unlike architects, we buy properties. We don’t go looking for clients. There is a big difference. We invest the process of how we go about acquisition differently. Here you are seeing a piece of software that we developed. It is a map-based communication tool that we use in our office to identify what we have looked at in the past, associate news affiliated with different properties, connect to all of the zoning data and property transaction records that exist in the city. Even more than that, it is sort of like a dashboard in our office that helps us identify who we have spoken to in the past and enables us to see information in a different way.

This idea came to me in graduate school. This was my graduate school thesis. I had this idea for an architect-led development company that was also a contractor. I was recognizing that this is a broken industry. This is my timeline of how this went for me. I will get into a little bit about how our office works as well.

So it was my graduate school thesis in ‘95. When I graduated from school, I graduated with both a Master of Architecture and a Master of Construction Management. I kind of didn’t want to be told that I couldn’t do something, but rather that I could learn how to actually build here in the city. So I worked at a construction company for five years. While I was at the construction company, we won a design competition with my former roommate from graduate school for a federal plaza project for the GSA in San Francisco. In ‘98, we had taken on our first job. I was twenty-four years old and I became incredibly frustrated with the process of how we go about getting clients so I started to pursue development and tried to acquire sites as a way to build work for the practice.

Our first project as a developer, we won an RFP [Request for Proposal] in the City of New York for affordable housing. I then helped someone else acquire property. Then acquired my own property at 459 West 18th Street. In 2011, we dissolved the architecture practice formally, and I had already started Alloy already in 2006. So in 2016, Alloy had turned ten, and now we are working on a project that is a little over a million square feet. So we’ve been partners since 2006. We have worked on twelve projects. We have invested around $110 million of our own capital. We have managed about $430 million of equity. We borrow a lot of money. That is one of the big differences between architects and developers. It’s hard to borrow money as an architect. We are now approaching 2 million square feet of development at over 1100 units.

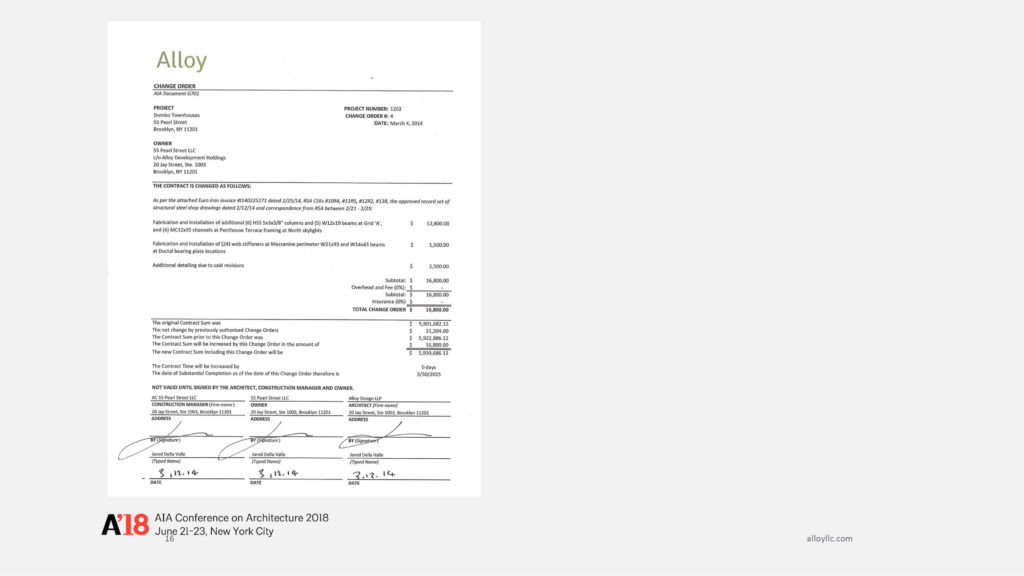

One of the big differences between our practice and an architecture practice is that we take a lot of risk. This is a note by business partners that one of my business partners left me with one of my legal bills that says, “holy shit pies” on it. We are spending about $120,000 per month on legal fees to manage the opportunities and to rely on different consultants on doing the things that we do. We things about things a little bit differently. This is a change order signed by me as the owner, signed by me as the architect, and signed by me as the contractor. We run our practice a little bit differently. Somehow our bank requires this formalization of the process that our industry has already defined. It’s the way we go about things. We kind of play by the rules, but don’t.

There are four partners. We have eleven employees and two admin, which makes 17 in total. We think of ourselves as more like 34 people though. Everyone in our office is like a swiss army knife. We are working on one project at once. You might be involved in marketing one day, you might be involved in construction another day, you might be involved in acquisition another day. There is only one person in our office that has real estate training. We are all architects. We have this incredible capacity and the economics are not rocket science. How much does something cost? How much is it worth at the end? We have run our practice that way.

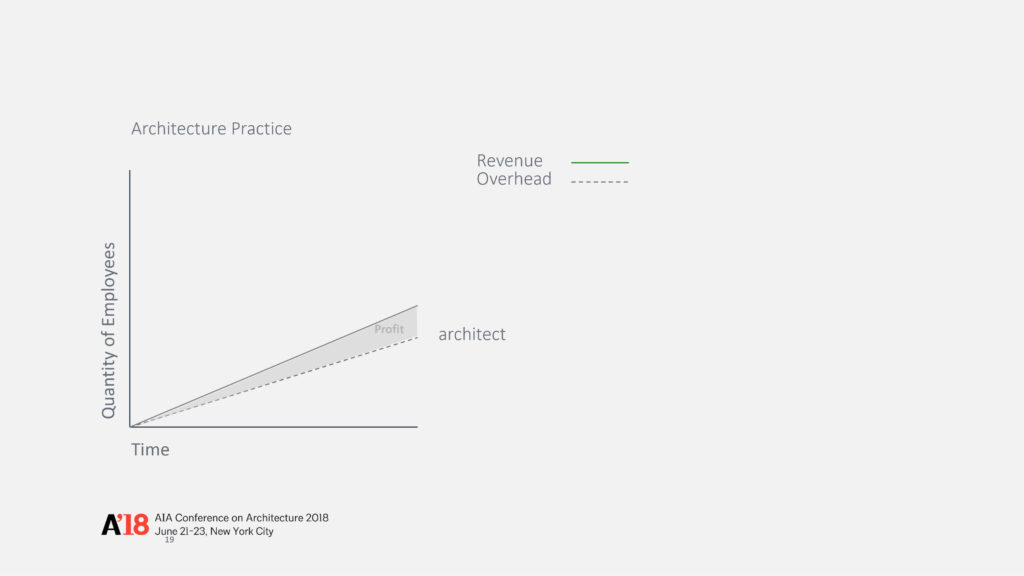

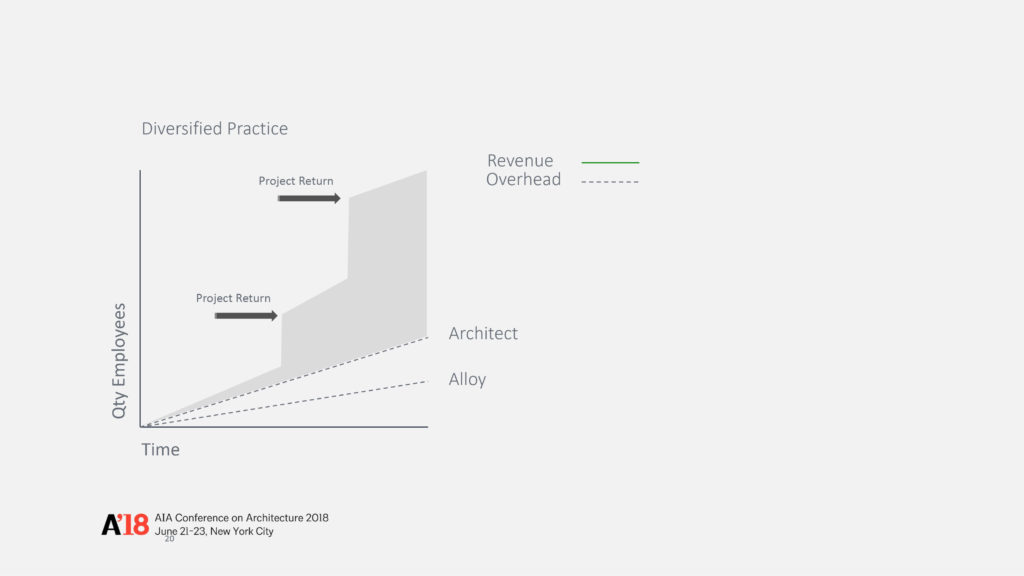

Eight of our employees are licensed architects. It’s been like a gateway drug for people. Once you are here, you can’t imagine unscrambling a scrambled egg and just providing service. So the typical architecture practice works off a pyramid right? You have employees, and you make money off of those employees. The more employees you have, the more theoretical revenue you can make. With a development company, we have that too right? We have something that we call “Money Day” in the office. My partner sends me a bill, and I pay it. We do that for architecture services, for development services, and for brokerage services. But more than that, we actually get the value out of the real estate. So we have these moments where at the end of the project, there is meaningful value there that we have created and achieved that’s different right? We have a project return.

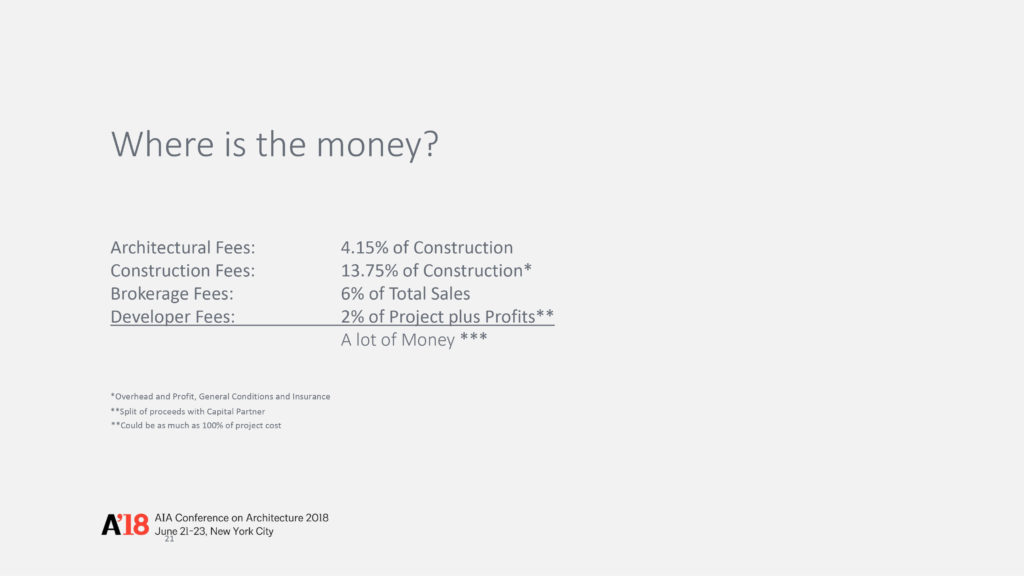

So how does it go for us? This is a typical project that we are working on now. A hundred million dollars is the type of project size that we like. So this is a general sense of how this works for someone like us. We pay ourselves architecture fees, construction fees (including general conditions and other things for our own construction company), brokerage fees (for doing the sales). Nobody is better at sales than an architect, I promise you. There is no broker who can outsell one of us. And developer fees. We pay ourselves developer fees every month. We get a developer draw. And keep in mind, that I am billing the same employees for the same tasks multiple times at the same time. At the same time, we get project profits. On one hand, we are taking all of this risk and it seems a little bit crazy, but if you add all of those numbers up, remarkably, I have created a hedge for risk. The market can go down quite a bit, but if I only make my fees, we have still done well, right? So I have protected myself market-wise by taking on all of these roles and ironically taking risk.

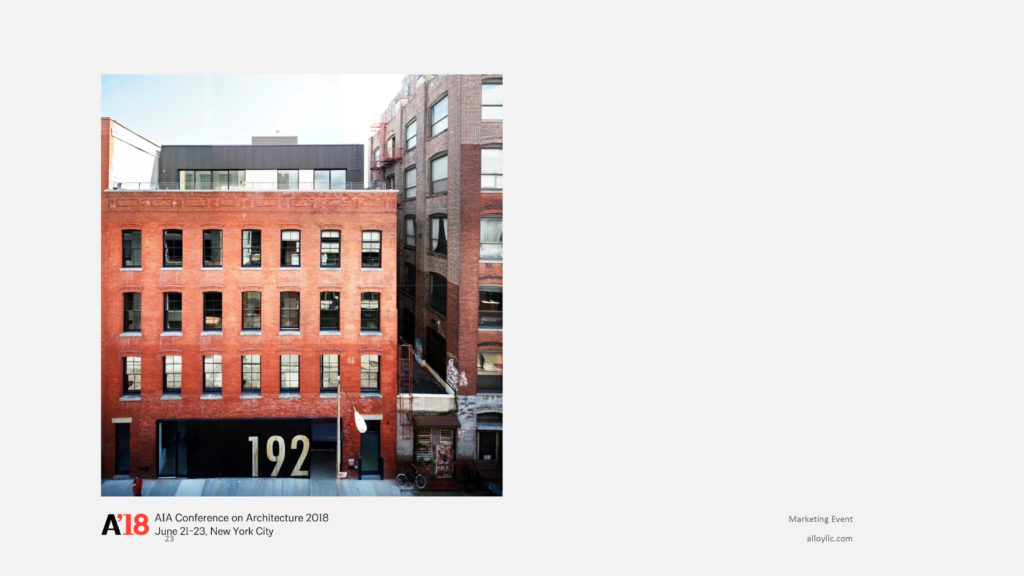

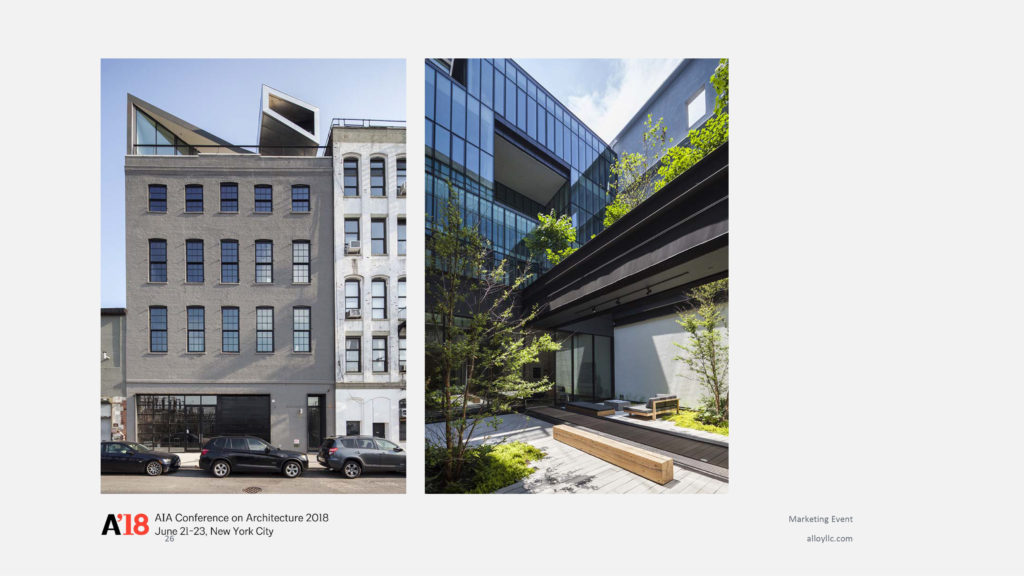

So we do things a little bit differently, and I will talk through a couple of projects really quickly. One of the beauties of being the Architect & Developer is controlling the message. This is a project we did in 2009. When the world was falling apart, we bought a small loft. We had a modest budget for the project. It was a 30,000 square foot project. We had a loft building. We bought a beautiful building. We had actually tried to buy it a few years earlier, and that buyer fell apart, so we bought it from the bank.

Then we hired a children’s book illustrator to come in. We gave him $2,000 and a can of white paint. And he literally painted the floor plans all over the whole building. That night we sold $21 million in real estate. We had one apartment left at the end of the night. It was a super scrappy way to talk about space in an existing building. It was a simple renovation in a historic district. It was one of our favorite projects in a way. It showed a re-thinking. Had we dealt with a broker, they would have said, “Well, you need a marketing brochure, you need a book, you need floor-plans, you need all this stuff.” We were like, “Nahhh, we’re not going to do that.”

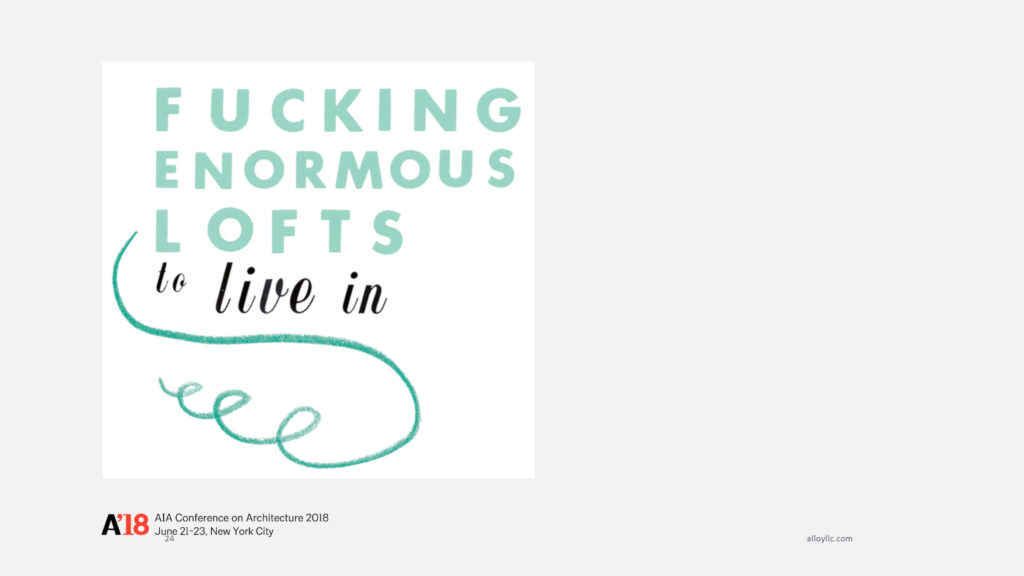

So sometimes we get carried away. We recognized that we had a lot of demand for that type of product. So the next building we bought, we brought the children’s book illustrator again. He rode off on his scooter and said, “I got it! This is the perfect idea.” So he came back with this. We were like, “Huh. Maybe we’re going too far? Maybe we need to edit.” So we do have some editing capacity in controlling of the message and the idea. In this instance, we were selling space in New York City. These were large spaces with 3-thousand square foot apartments with 14-foot ceilings. We were trying to connect people to the idea of space being the most important thing. So there are projects like that.

This is a 35,000 square foot project where we are doing these big apartments, and making these big decisions, some of which I might not make again. In the image on the right, we had a block through building. We cored out the middle of the building and repositioned the bulk on top of that building, which is the image on the left. It is in a landmarked district, which adds complexity when you are taking apart a building that was built in the 1880’s. Again, another successful campaign. We sold out in two-weeks with this information with just an existing building and some very simple collateral.

Over time, our projects have largely been in a single neighborhood, literally a block from my office. We can’t tell if that’s just because we’re building a reputation there and sellers are coming to us, or because we’re lazy. But this is a project we built in our neighborhood, a block from our office. It started our construction company. These are some of the first passive townhouses ever built in Brooklyn. They have a ductile concrete facade. I think taking risks like that, where we think about the history of this neighborhood, which had some of the first reinforced concrete buildings, built in the early 1920s by Robert Gair… pre-Brooklyn Bridge. We took this idea of reinforced concrete and pushed it to its limits with a product like ductile and created a new townhouse typology that looks more industrial. We took the risks on the aesthetic choice and prioritized where we would put value and how those would fit in with an existing neighborhood. Again, how we would think through delivering a product that was unique to the neighborhood by delivering something that was on the edge for sustainability purposes.

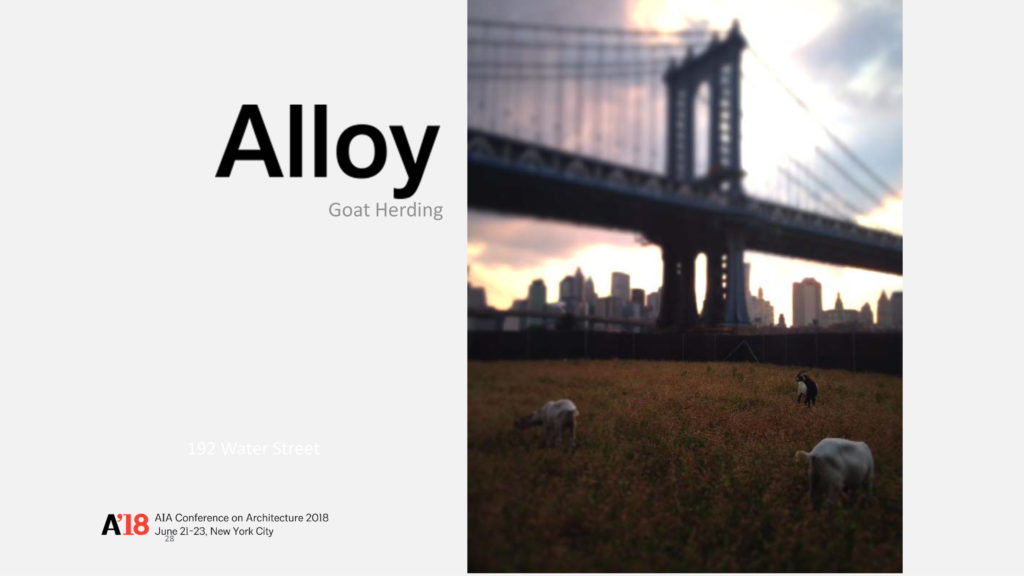

So, this is a joke, but not a joke. We started to get involved in these Public-Private-Partnerships. We were awarded a site through a public RFP in Brooklyn Bridge Park. We started to really enjoy the early part of sales and marketing. We were trying to figure out what we were trying to do here. We were building inside of a public park, so we decided to build a park in our site, while the park was in construction around us. So we planted a big field of flowers. In the end, we were like, “Well we have to take this down before we start construction. How are we going to do that?” So someone in our office was like, “We need goats.” I go home that night and my wife was like, “What did you do today?” I was like, “Well, I had to find a shepherd to sleep in the field with some goats, so that the goats wouldn’t get stolen overnight.” So we planted this field of flowers, we brought in some goats, I found somebody to sleep in the field with the goats. Unfortunately, one of the goats broke free and started running through the neighborhood. So not everything goes according to plan. It enabled us to create something that was memorable in the neighborhood. This idea that place and working in a public park was a privilege and trying to connect that to a place that had no address. It was in Brooklyn Bridge Park, so we called in the John Street Pasture.

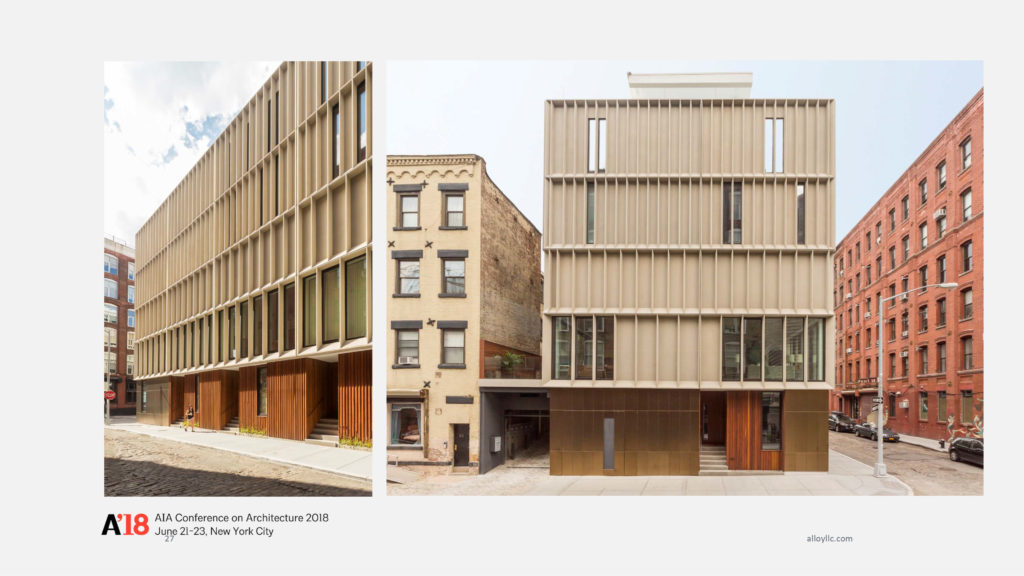

The building itself, we start to jump scale as a practice. This is 130,000 square foot building. We understand the sort of historic context of this neighborhood and the typical relationship of window typology. In this neighborhood, because you are on the river, the views down low are actually better underneath the bridge. So we pulled all of the windows forward and proud of the building. We inverted the typical relationship where the windows get smaller at the top. It starts to create this sort of double-take, where it feels like it’s part of the Landmark District. We built a really beautiful brick building. The bricks actually get smaller as they go to the top as well. It changes the nature of the reflection to a clean reflection with a broken plane rather than recessed windows which is common in the neighborhood. This started our Public-Private-Partnership model. We donated a space to the Brooklyn Children’s Museum in this. I always joked with my partner that it would be faster for us to donate a museum than it would be to get called by someone to design one. So we are starting to do that.

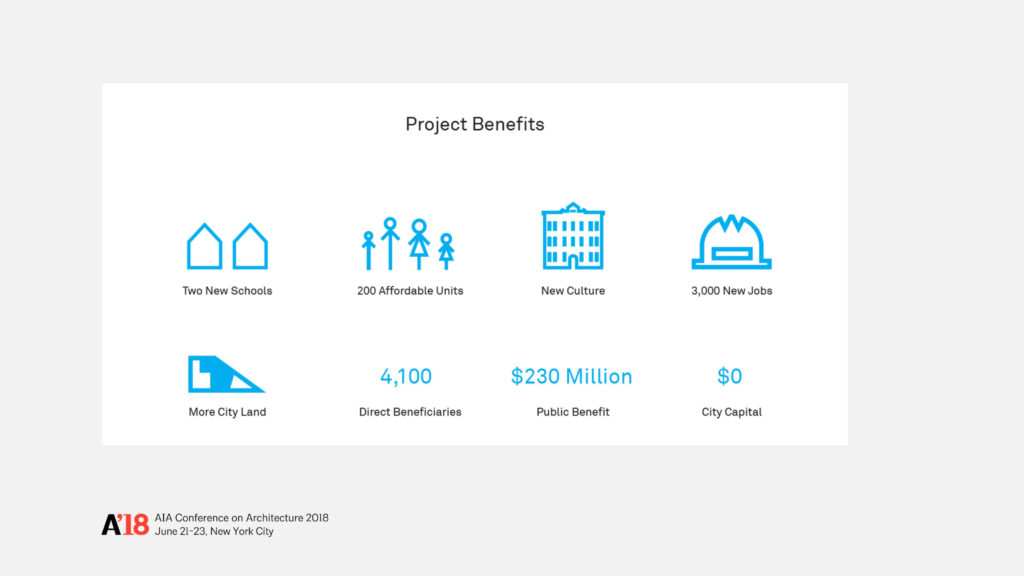

Community engagement has become a really important part of our practice. We don’t spend money on marketing. We spend them on the communities in which we are working. We are working on a large project now in downtown Brooklyn that is going through public review process. It is over 1 million square feet. During the process of development and while we are pursuing entitlement, we have sponsored six projects. We spent over $1 million on early public engagement. We have done everything from creating a system for court-involved youth to get diverted out of the court system through arts education. We donated a space to non-for-profits and dance and art organizations. We created community festivals. It is about this idea of building awareness in the communities in which we work to connect to people, the places we make. We are making real estate, and we are selling it, but the places we make, we want them to be valuable. We want them to have this alternative sense of value where communities can be proud of participating in them. And proud of having them as their neighbor. So the project we are working on now has a series of features which we are starting to really leverage for density for scale. On this new project, we are donating two public schools with over 700 school seats. We are creating over 200 affordable housing units. We are donating one of the existing buildings to a cultural institution. It will be over 15,000 square feet. We are creating over 3,000 jobs with that. We are swapping our property with the city for more land so that the schools can have large open-space features like gymnasiums and auditoriums which they currently don’t have. The cost of this benefit for the new project is over $230 million in public benefit, for zero dollars to the city.

Projects like this are what we are working on, which is a 980-foot tall building with another phase that is 500 feet tall. It sort of expresses to me what our role is as an architect. We think of an architect in a traditional way where we are providing services for people. But, ironically the further I get from providing architectural services, the closer I am to being an architect. The definition that is shown here, “The person who is responsible for inventing or realizing a particular idea or project” is how I perceive our practice.

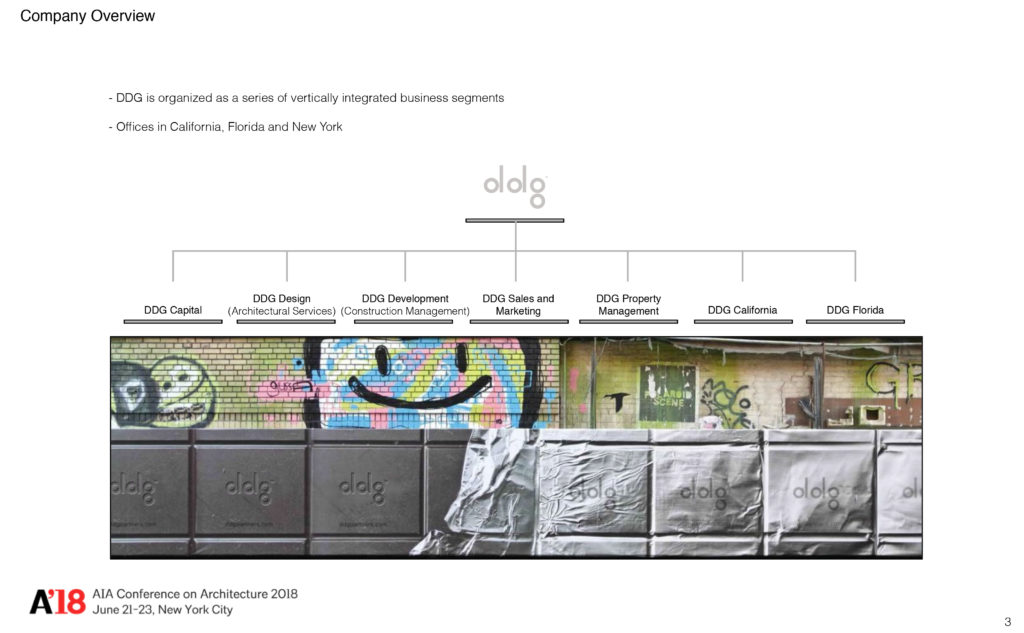

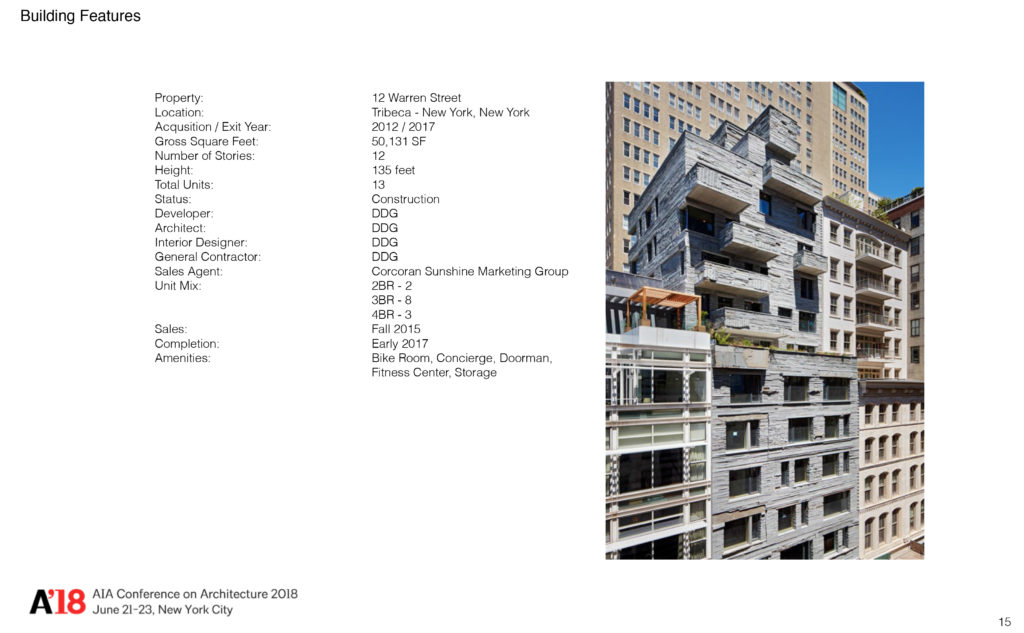

Peter Guthrie – DDG

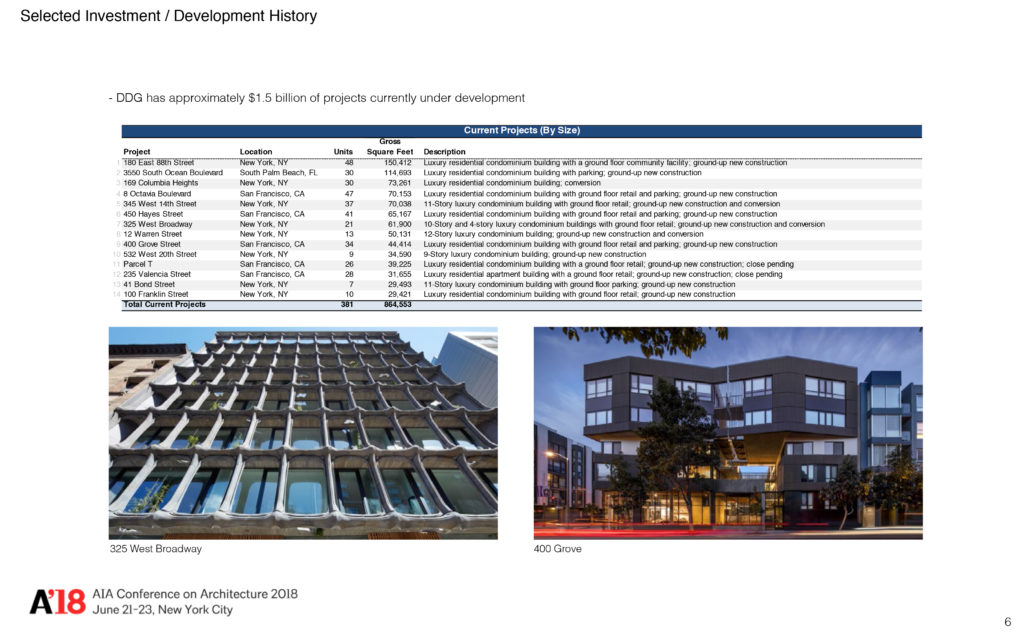

Well done, that’s a tough act to follow. I am Peter Guthrie of DDG. We started DDG in 2008 and been going ever since. We do a lot of the same things that Alex and Jared are doing. We could probably give each other’s lectures. It might be a fun thing. We will try it out the next time. We design-develop-finance-construct and then manage our projects. We are vertically integrated and this is a horizontal slide. We are doing a lot. We are building in New York, San Francisco, and Florida. We are also looking at a project in LA right now.

I studied art history and sculpture, and then went and took a Masters in Architecture. I came to the city and I did a number of things, but I was always interested in making and building. My passion is that. It is at my core. I came to the city and worked for a metal worker in DUMBO. So I know your area very well, Jared. That was super fun working for $10 per hour shaving welds. That then led to a job with Peter Gluck with GLUCK+ Architects. For those that don’t know who he is, he is a great mentor. I learned the design-build philosophy from him. I had done what I would consider design-build work. At Yale, we build a house for folks in the neighborhood as part of our first year building project. It was a great way to see a building through. I had also worked for Habitat for Humanity while I was at Duke. I think I added in my bones that you could really make a difference by getting out in the community. That was at least the difference that I wanted to make. I wanted to get out there and figure out how to get something done. When I moved to Brooklyn after working with Peter for a while and wanting to do my own thing, I, like Jared, did some work. I built a house for a friend. Then I had that same sort of feeling of dread of beating the pavement looking for a client.

So I was looking around these buildings in Brooklyn with Fedders air conditioner units in the windows and thinking, “What are these guys doing? What is the secret? How could we do a development project?” I was talking to some guys in the neighborhood and it came down to something that certainly wasn’t rocket science. “300! 300! 300!” I was like, “What’s that?” “You buy it for $300, you build it for $300, and you make $300.” And it’s that dumb and that simple. The pro forma was a back of napkin idea. You buy it for X. You build it for Y, and you sell it for Z. Hopefully, you have done your math correctly. I had done that already on a very small scale. I built a desk. I bought the wood myself. I could break it down, and I think all of you guys, those of you that have studied architecture, have a great skillset to break problems down into very simple components and not get overwhelmed.

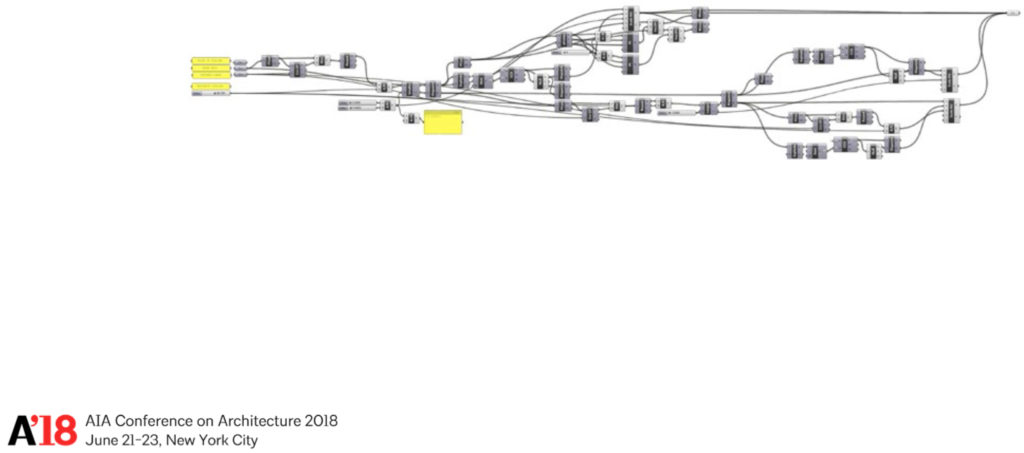

This complex thing that is blurry… and I hope you can’t see it specifically… because it may be confidential… it has a series of parameters. I have a slide later on which I love. It is my grasshopper script slide, which is parametric design thing. We use it. It’s fun. It’s essentially the same thing. Architecture, and many things in life are a set of parameters. What you do those parameters and all these little toggles are related to time and money. Lurking beneath all those numbers are choices. There are a myriad of choices that you can make. That is the fun of it for me. Every day, I wake up thinking of the opportunities that are going to be on that day. In talking to a banker, talking to an electrician, talking to one of our architects, talking to one of our construction managers, talking to one of our building managers.

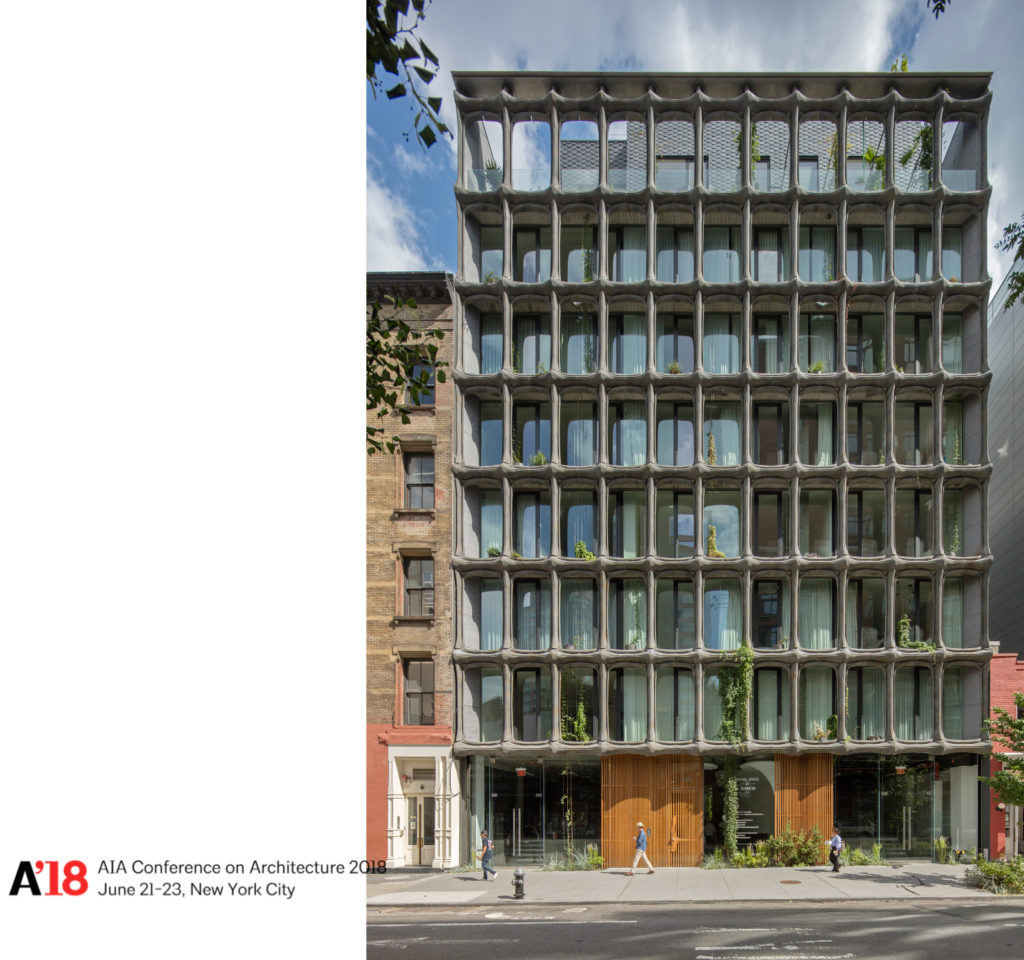

So this is our first project in Manhattan. It’s 41 Bond Street. It is a bluestone building. It is in a Landmark District, so we had to come up with a way to make a ground-up residential building in this Landmark District with the auspicious start of being right across the street from Herzog and de Meuron, and my old professor Deborah Berke. It was just not where I wanted to start. I go to the site and I see school groups coming through and they’re all oogling at Herzog and de Meuron. I love their practice. I know there are money people who don’t love that building, but I do. I love that building. It is something that I could never make. We knew we had to do something different. We needed to be chilled out and respectful to this neighborhood and try not to draw too much attention to ourselves. So we buckled down and found a material, this bluestone. We had done a building down in TriBeca already, so I already had my feet under me. It was still standing, so we thought we could keep going. What we did was take craftsman… and one of the secret little weapons we found in the numbers is the labor. I agree with Jared. Unfortunately, on this project we are working on right now in the Upper East Side, we have become the concrete contractor. I didn’t get into it to want to control every little piece. But you do find that it is to your advantage. So we have our own masons. We bought the stone and we shipped it down and we would cut it and carve it on site. Not radical craftsmanship, but just a step that is really hard to get in the direct marketplace if you don’t have direct labor. It is a rigged thing. By having direct labor, we can pass that profit on to the project itself. We are not taking that profit and putting it into our pocket. We are putting that profit into the project.

That is Mickey over there on the right putting that door frame in. We did everything on that project from soup to nuts. From the facade, we put in all the windows and all the interior framing. All the bathrooms, and all of the trim. All of the specialty trades. This is a team that I had built up over the previous 5 years before starting DDG. Again, getting into it from one guy who I hired as my grease, my general conditions, just to go around and help the other trades. We found that the other trades, like my door guy was not making it. He was just not getting the doors in and plumb. So I would ask Juan Carlos to go and fix it. Suddenly, there was somebody else we needed to bring on. We became, on the next project, the subcontractor. We did all the framing and all of the specialty trades. We got so tired of fixing other people’s work, and we were finding that we were training our own crew. That is a drawing on the wall. We like to break down the mystery… and I learned that from Peter Gluck a lot. We really labor over how to communicate, how to break down the barriers of this world of architecture and design and make it something that is more collaborative. We find that that interplay between all of these specialist or these artisans, our tradesmen, is essential. It results in a fantastic and unexpected interplay, where our details get better and better.

Jared is way ahead of me on this platform. You [Jared Della Valle] are really in an admiral place in terms of the community work that you are doing. We are just stepping into that field. This was a start for us, where we realized that there was something that was happening that was a little bigger than us. We could provide a platform. That platform could be synergistic and be win-win. We built a building in the Meatpacking District. We came up with an idea. I just asked a question. We had these mesh wraps that go around the scaffolding, a black mesh. What if we did something different? We could tie that to our marketing. Yeah ok. We could design something… in fact, we had already designed a sort of thumbprint thing. Then we asked another question. Who could we partner with? The Whitney was just moving downtown. Does anybody know anyone at the Whitney? My partner Joe did know somebody at the Whitney. So we talked to them and Kusama. They were having this great exhibition of Yayoi Kusama. It just so happened that the exhibition was coinciding with Louis Vuitton opening up 450 stores worldwide. We couldn’t have imagined a more incredible marketing boom to tie our building to the Whitney crossbreeding opportunity.

It turns out her studio was on 14th Street. Her dots sort of connects to the hallmark of this building, which are these bricks that you make. The guys making these bricks, and I have been over there to see the guys making them, as he is taking the mold out around the brick, leaves a little thumb depression in there. You can see it on the right. It is so sublime that you will never see it. It is buried in the wall. It is this incredible enigmatic touchstone of the human component of these handmade bricks that come from Denmark. To me, that little thumbprint connected to Kusama’s dots, which was this sort of invisibility shield.

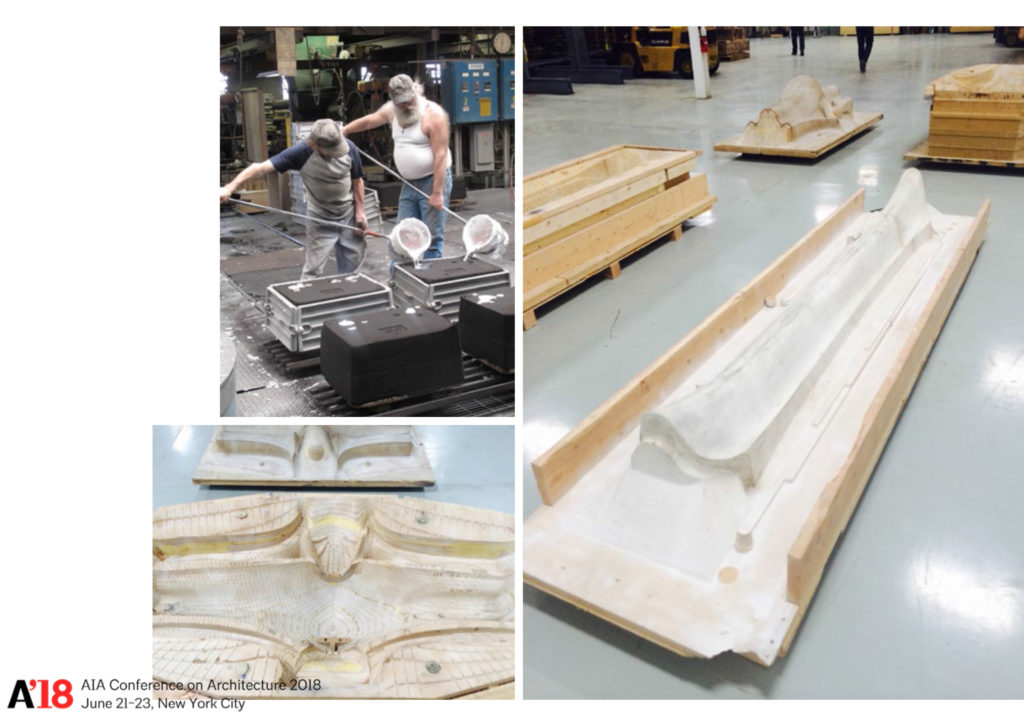

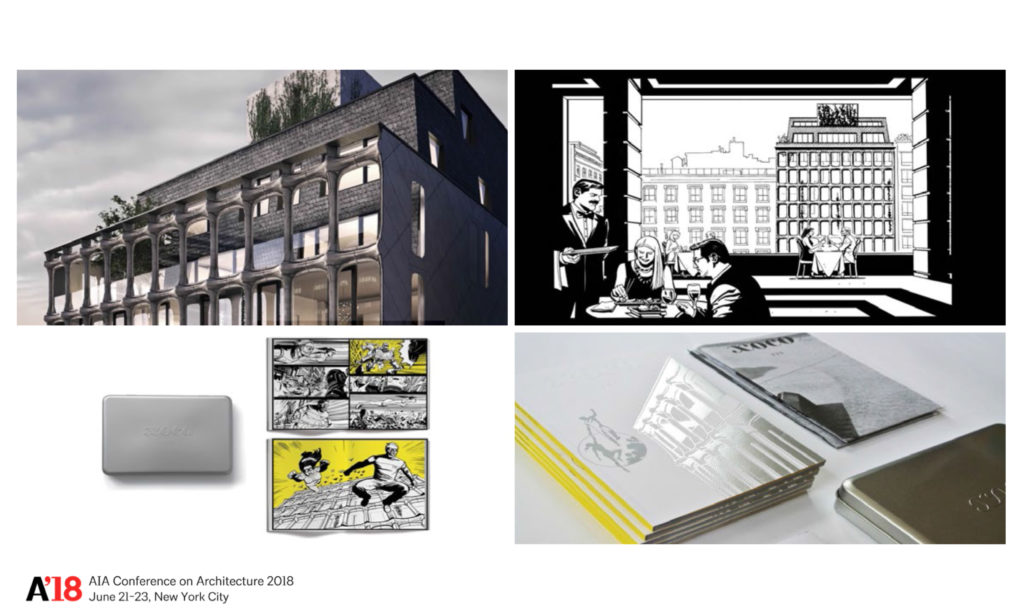

325. Some developers, not these guys [Alex Barrett and Jared Della Valle] will often look at this area as another one of these places to try and get around something. Oh, they’re smarter, they’re going to get under and around and play the system. We took a different tact. We said, “There are architects sitting in this room who are going to judge this project. What if this was a collaborative enterprise? What if this was like a crit back at school?” We went kind of overboard in making basswood models and looking at the tectonics. This building is in SoHo, so it is in the cast-iron district. We looked at the history of cast iron and component parts. We thought deeply about it. We entered into a discussion with Landmarks and showed them what eventually becomes a building… while trying to reinvent a language that is connecting to the cast-iron district.

We end up working with the ZZ Top boys. They were awesome. They make chevy engine blocks in the middle of Pennsylvania. They were fantastic. They couldn’t believe that we wanted a weird burlap texture to our aluminum. We were gravitating to these pieces in a cart. They were the rejects. They were so used to military specs. This is us playing with the modeling and the finishes. This is the texture, a burlap finish. All of this craziness was supported by New York City Landmarks. It was a fantastic process. It was heavy. They had great feedback. We allowed the process to force us, but they were instrumental in making us try harder and made the details for architects in many ways. That was fun to realize. They really wanted to look at how the side of the building and our aluminum screen integrated. I thought, “Man, that is crazy. The Landmarks is totally having a modern architecture dialogue.” It was not what you would expect. The knee-jerk anti-modern rhetoric or stand that some people expect from Landmarks.

Our marketing… like the Kusama, we are partnering with Shawn Martinbrough, who had just given a TED talk. He is doing something the George Lucas now. He is a noir-comic-artist. He was instrumental in helping us find a story. Like what Jared was saying about creating opportunities outside of the traditional selling model, that was the thing that we learned form Kusama. In all of our projects, we do partner with other artists or artisans. We make books for them as well. They’re artworks in of themselves. We will do crazy things, like a billboard.

This is a story because this was an old chocolate factory. So we came up with a storyline of these two heroes who have to battle an evil robot. Ultimately they save the day by saving this chocolate recipe. I dunno. Somehow it made sense to us. Why not have a little bit of fun? It is tangential marketing. You will see this in luxury goods and Louis Vuitton and these Gucci places. Ferragamo had some illustrators do work. We are riding on that wave. I think that tangential marketing and the spirit of collaboration is what drives us. What I didn’t show earlier, is that the Kusama collaboration ended up influencing our grill design. So our HVAC grills in the apartments are this dot matrix that we would have never have thought about had we never partnered with her.

This is a building in TriBeCa. More bluestone. It was fun. We laid it out in a field in Long Island.

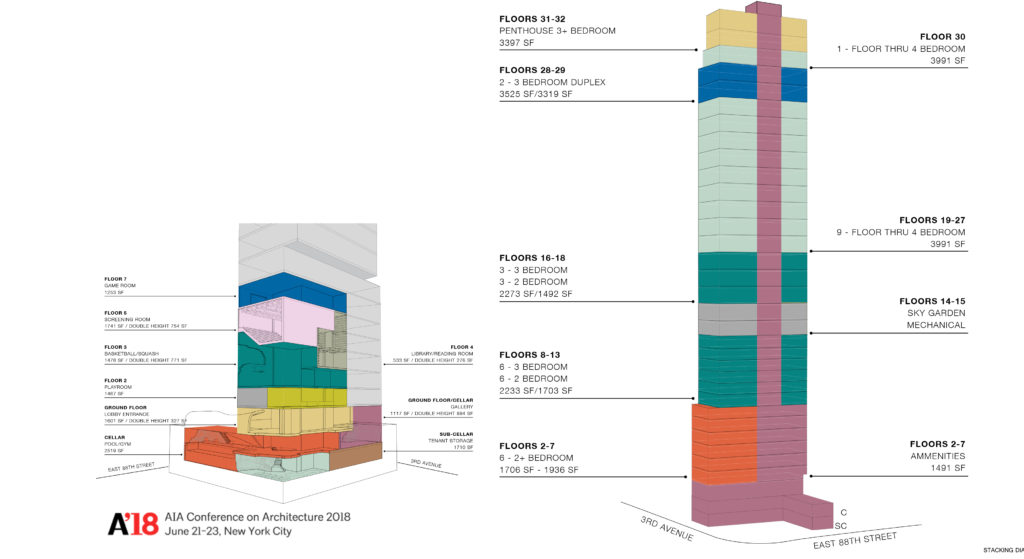

88th Street is a tower that we are doing on the Upper East Side. We do a lot of studies. These are the stacking plans of how many units. It is primarily residential with a commercial component on the first floor. This one was weird. It has this whole amenity package, which turned out to be more or less necessitated by the form and the percentage rules governing that site. It forced us into making all of these amenities. Modeling. We do a lot of 3D modeling.

Here is my favorite grasshopper script. That is crazy. I love it. This is the mess of the parameters. Then it results in this, which is actually the fenestration pattern. It literally tied into 10 percent and the different percentages of legal light and air for different rooms. Whether it be secondary bedrooms, bathrooms, or living rooms.

This is our brick mock-up. This is our artisan Jan Hooss, working in stucco. We like to go macro to micro and find that these very micro collaborations work their way back into the macro. These are the arches in the top of the building. We are currently on the 28th floor, and there are 31 floors. So we’re getting close. Brick started.

Just leaving you with this last slide of the sales gallery. This is Stephen Quinn on the right, who wrote the book on dioramas. He is the foremost diorama authority. He works with the Museum of Natural History. When you go to the Museum of Natural History, he has a book in there. It’s fantastic. We needed to make windows in the sales gallery. Many people are offering these digital prints. We said, “Nah, that’s crazy. Let’s talk to the folks at the Museum of Natural History.” Sure enough, they were really interested in partnering with us and we made this diorama of Central Park. For me, it is that touchstone of just asking a question, “Can you do this a little differently?” If you approach it with some great people and some passion and energy, some fun things can happen. Thank you.

James Petty – Architect & Developer

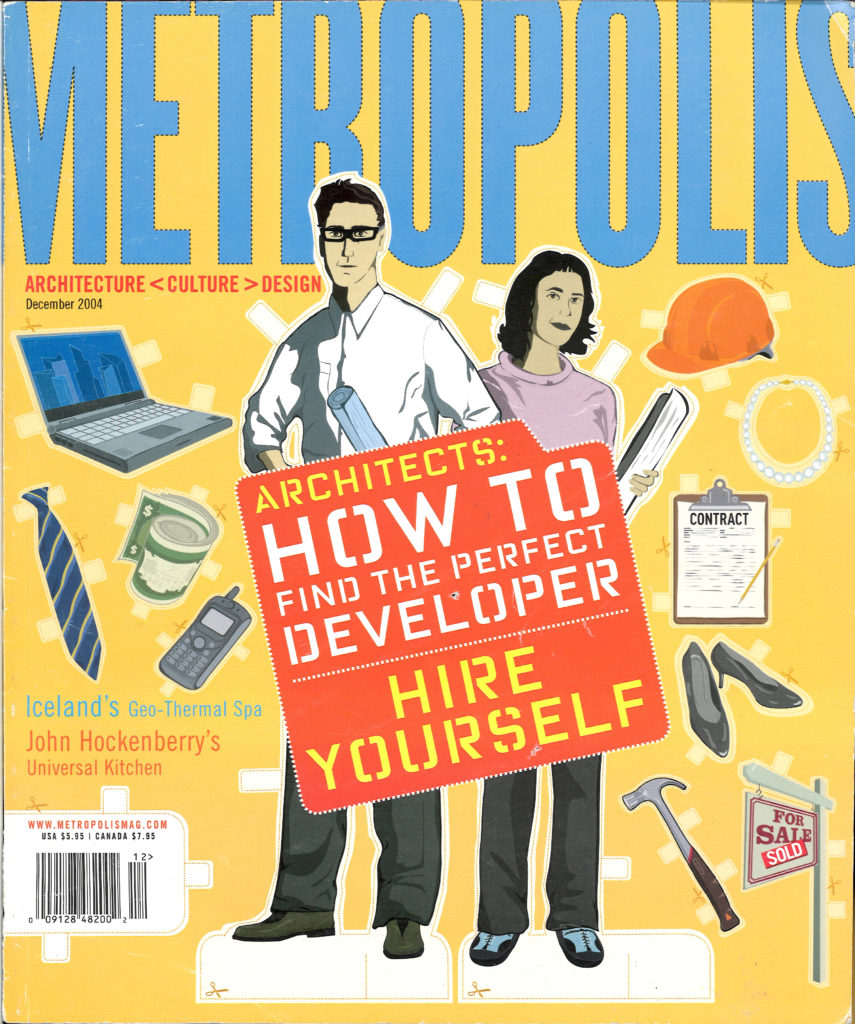

I just wanted to talk about a few things real quick. What these guys are doing isn’t new. I know that the AIA hasn’t talked about it for a very long time, but in 1777, John Nash took a lease assignment on a piece of property in London and developed 8 units. That was 241 years ago. He later designed the Royal Pavilion in Brighton and Buckingham Palace. That is what you probably know him best for.

So how do you do this? I want to break this down into a couple of quick steps for somebody who is an architect trying to get into the development.

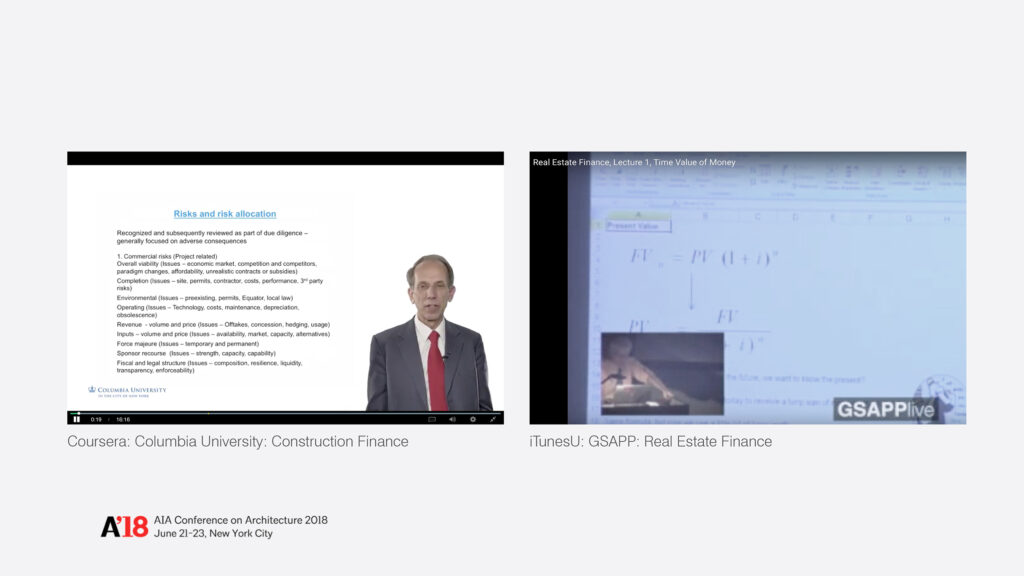

The first step is that you’ve got to educate yourself. You need to take the time to learn a lot. There is a lot of terms that you need to know: the NOI, the ROI, the NPV, the IRR, etc., etc. You can get a real estate degree, but there are a lot of universities who are starting to put more of their content online for absolutely free. Coursera, EdX, and iTunesU are fantastic resources [more info here]. They may sometimes look like they are behind a paywall, but if you work your way through it, it is free. The Real Estate Finance course by GSAPP is really one of the greatest things to start out on. Pro formas. You need to learn how to read them. You need to learn how to take them apart and put them back together. But really, it is a simple process. You buy it for X, you put in Y, and you get out Z in the end, but you need to understand what that process is.

Real estate is a debt-financed industry. If you have student debt, you need to get it refinanced. If you have bad credit, you need to get it fixed. You need to put yourself into a situation that when you go to an investor or a bank, they see you favorably and they will give you money. You also need to start putting money together. You are going to have upfront cost for land acquisition, consultants, and entitlements before you will ever pull a construction loan or get an investor to put money into your product.

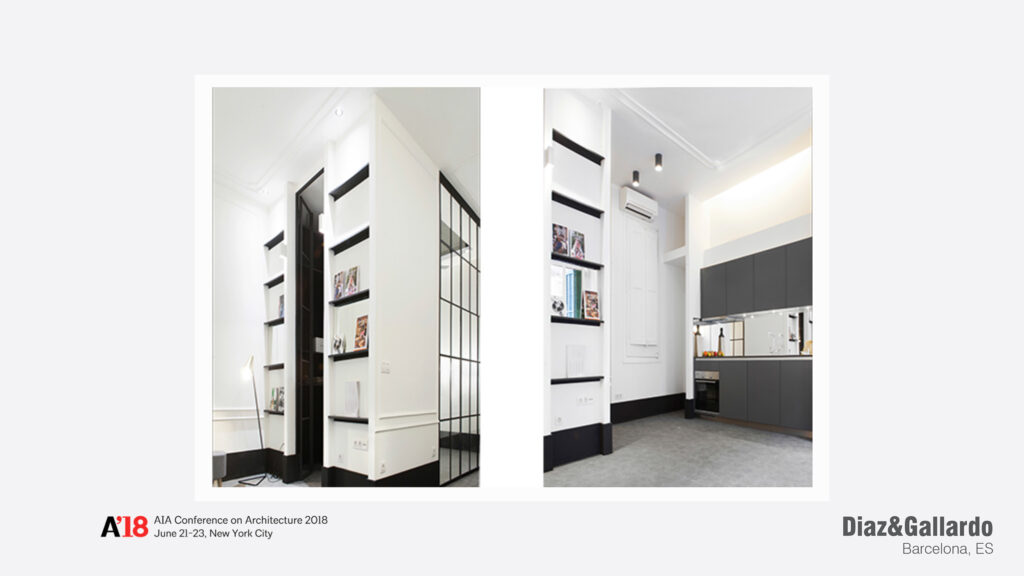

You need to figure out what you want to do. These guys [Alex Barrett, Jared Della Valle, and Peter Guthrie] are doing big projects that cost a lot of money, but a lot of people are starting out in smaller ways. Diaz & Gallardo is a couple in Barcelona who lost all of their clients in 2008. They started buying small apartments and renovating them themselves. Now, they’ve decided that they don’t want clients anymore and they keep doing this. They’ve done over a dozen.

Jose de la Cruz borrowed money from his brother and his 401k. He bought a house for $80,000, put $80,000 into it, and sold it for $280,000. All while working a full-time job at an architecture firm. So his day-job Monday through Friday. He worked on this house Saturday and Sunday, and he still doubled his money on this guy. He is working on his next one now.

You can do a new build. Mike Benkert also has a full-time job. On the side, he bought a $25,000 lot at a sheriff’s sale. He works nine-to-five, and on his lunch breaks, he checks on his contractor building his project. This is his second house and he’s getting ready for that third project. It is important for him to keep his day job for the financing. Banks need to know that they are going to get their money.

This is The UP Studio here in New York City. They are a young couple of guys doing a lot of interior work. They wanted to do a modern house. Nobody was hiring them to design a modern house. So they bought a piece of land and did it themselves. While it was under construction, they had several people walk by. They said, “I love your house. I’d love to hire you as my architect.” Now they have several projects. They are making legitimate buildings and they are on to their second development.

Multi-family is tough. What these guys [Alex, Jared, and Peter] are doing requires a track record and to be heavily capitalized. This is Cary Tamarkin. He has a lot of projects on the High Line. They’re beautiful. Like I said earlier, if you go to bit.ly/archdev, you can download a map onto your phone, and you would be surprised by how many buildings are actually developed by architects.

With multi-family units, pre-selling is a really big deal. This is a great example of where you can be clever. To be an Architect & Developer, you need to set up a lot of entities and a lot of contracts between yourself. Onion Flats was able to get the

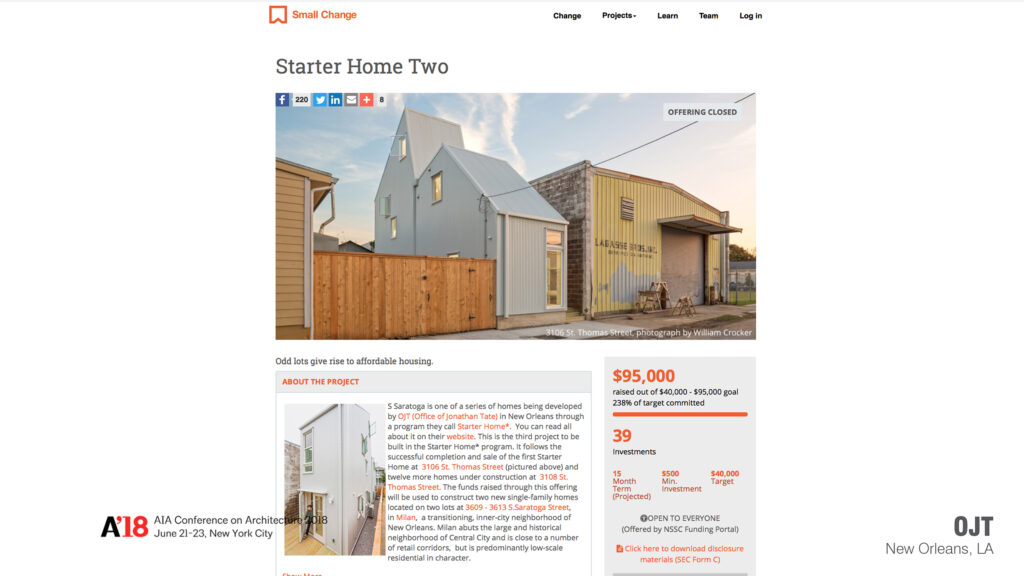

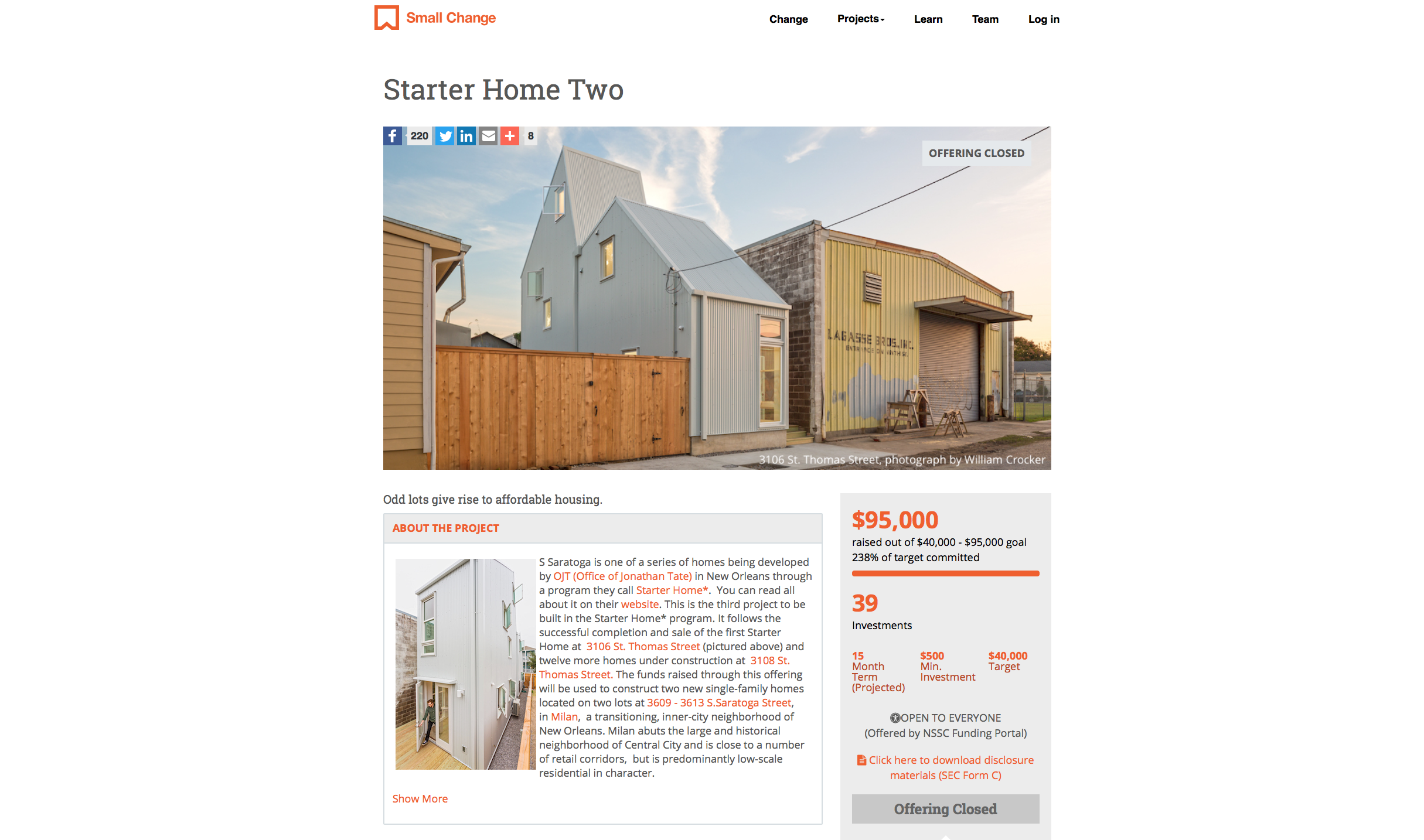

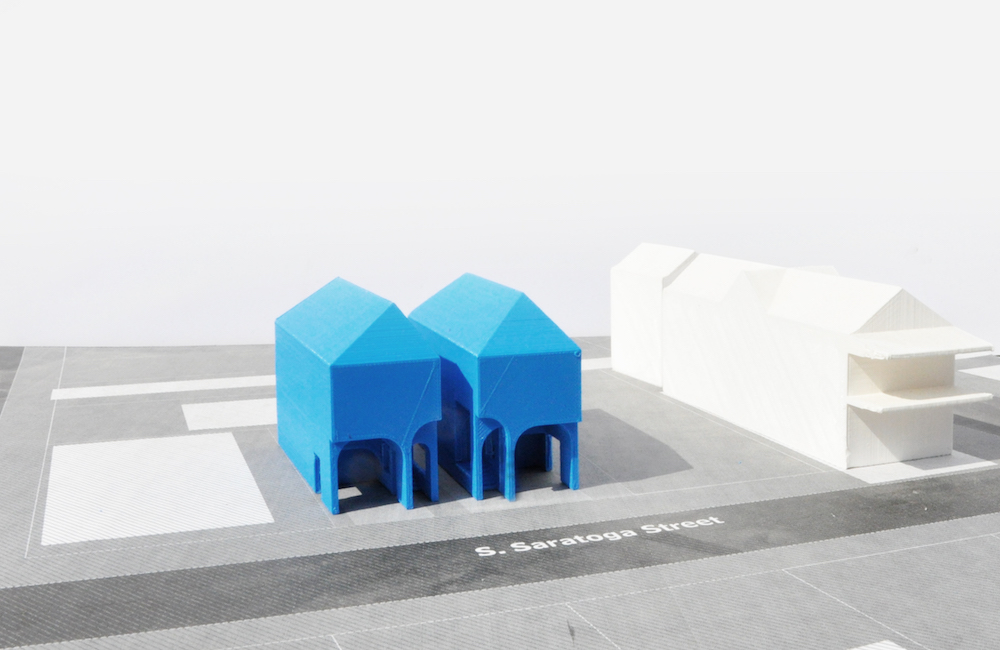

You can also play with your own academic ideas. This is Jonathan Tate down in New Orleans. He started with this little sliver house on the right, which has been getting a lot of press lately [see here]. While that was under construction, which he developed, he bought the land all next to it. Zoning gave him the right to do three single-family houses. He didn’t want to do three-single family houses. He was interested in a tighter, denser neighborhood in New Orleans.

So he created a co-op on the land which allowed him to create ten detached units. It created a really interested little network in what he calls Starter Home*. It is an academic exercise for him that has also become lucrative.

In downtown San Diego, there are these three guys [RAD LAB] who had a thesis project to create an urban park. They wanted to create it with no money… because they were in grad school. So they raised $60,000 in a Kickstarter to pay for a bunch of up-front fees. They went to the mayor’s oce. They said, “Look, we were able to raise a bunch of money, can we get something from the city.” So the city pitched in. They gave them a 2-year lease for cheap on land that was later to be developed. Then they got some investors. They got each one of these tenants to sign up. They made the tenant pre-buy their shipping container and pay RAD LAB to design the thing. So RAD LAB was off to the races without much money. Now, each of these tenants pays RAD LAB rent each month.

So this is great. What these guys [Alex, Jared, and Peter] showed you was great, but then there is the real reality of the situation, right? [I am an architect. I have no money] So, how do you figure out your financing? The truth in real estate is that nobody has any money. It is always other people’s money.

You need to find investors. Maybe that structure is something along the lines of offering a 10 percent preferred return and split the profits 50/50 afterwards. Maybe you get a partner where someone else comes in and puts in all of the money while you put in all of the work. In the end, maybe you get some money out of it. Or you get a construction loan, which might have terms of 4 to 6 percent interest (although that is getting higher these days). They will give you up to 70 percent of the cost of construction. They aren’t going to give you all of what you need, which means there is still going to be a gap in what you need. That can be problematic, because you still have to ll in that 30 percent gap

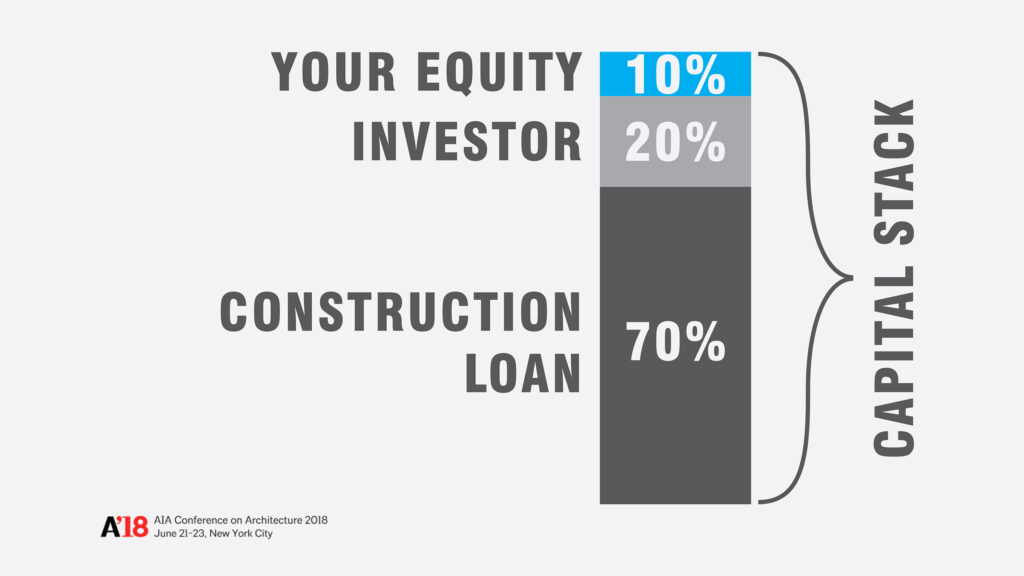

This is where you get creative. You use your skills to create what is called the capital stack. There are a lot of ways to do this, but this is just one way. You get a construction loan, find an investor to bridge the gap… which is a loan on a loan… the risk is higher… but you decrease your equity to 10 percent. This is a very real scenario of how people develop real buildings. But how can you get that equity even lower? I have a few little thoughts on that which I want to share with you today.

One of which is architecture is equity. When you have all of these diferent entities, and they [Alex, Jared, and Peter] talked about that before, you can use your fees as an architect that are early on towards your position in the loan. Banks will recognize that, so long as you create a paper trail. Contracts with yourself. “Money Days” like Jared was talking about.

Another idea if you want to take a little bit less risk is that if you have an existing relationship with a developer, you can do what GLUCK+ did. We put in sweat equity into the front end of this project. Basically, the architects worked for no fee for a percent stake in the ownership of the project. This is a rental project in Philadelphia. Now GLUCK+ takes in a percent of the rent every single month. You have to realize that for a developer, all of the fees at the very beginning of a project, which is when an architect does most of their work… before entitlements and before public permissions… is the most at risk for a developer. That is when the architect is most valuable. If you are able to work out that kind of an agreement, it also means that if the project doesn’t go through, you don’t make any money.

Crowdfunding is a very interesting thing that is going on right now. There are a couple of reasons why. This isn’t your Kickstarter. It is a little bit different. There are a lot of projects that you see on Kickstarter that never gets built. So much wasted money. ZUS is an architecture company it Rotterdam who wanted to build a bridge. They raised 100,000 Euros by ofering to CNC route the names of the donors in the walls. The city was like, “Great! People actually want this thing and are willing to put their own money into it.” So the city put the rest of the money up and they built the bridge.

This is the REAL type of crowdfunding that is going to come into play. Before 2012, in order to become an investor in real estate, you needed to be an accredited investor according to the SEC [Securities and Exchange Commission]. This meant that you needed to be worth more than 1 million dollars. Since then, the JOBS Act has been passed. Every single year, that regulation has been coming down to the average person to where a regular person could invest $500 into a project. That is what Kevin Cavenaugh did. This is not a rendering, it is a real building in Portland. He spent 15-months and $200,000 in attorney fees to get SEC approval to be able to crowdfund this thing. But he was able to raise $1.5 million as part of his capital stack. Which is pretty incredible. This project just finished construction a few months ago. In December, he did a second crowdfunding campaign. He was interested to see if investors would take less of a return for a social cause. His next project is housing that subsidizes homeless housing in Portland. He offered investors a 5 percent return, which is very low. Within 3 days, he was able to raise the $300,000 he was looking for which proved his point that people were willing to take less of a return for a social cause. It is pretty interesting.

This is the next level. This is regulation CF of the SEC JOBS Act. This is Jonathan Tate again. A few months ago he was looking to raise $95,000 as part of his capital stack. It was $95,000 of crowdfunding, $40,000 of his sweat equity as an architect, and $400,000 of a construction loan. Except instead of having to go to the SEC, he partnered with the website Small Change. It is a website which you can register on. They are already an accredited investor. He didn’t have to do any kind of upfront legal work. He just raised the money and now he is building the building with very little of his own money in it.

Another program is the FHA [Federal Housing Authority]. Everybody needs somewhere to live. If you are willing to live in your project, you can actually purchase and finance construction of a building with 3.5 percent down. That is what Zeke Freeman did for his very first project in Denver. This is his own house. He got a single loan that was $130,000 for the property and $100,000 for renovation to do whatever he wanted as an architect. It cost him less than $8,000 all in.

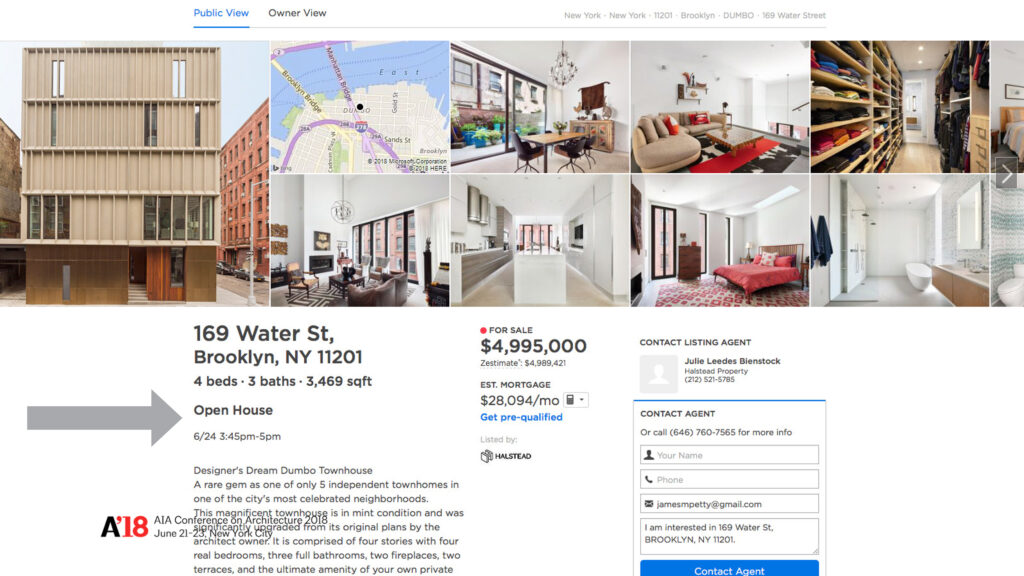

The next step is that you need to understand what the market is, what people are buying, what sells, and what people are missing in what they’re selling. The best way to do this is to go figure out what other people are doing through open houses. Sorry, Jared. Forget the AIA tours, one of Jared’s projects is having an open house on Sunday at 3:45 pm. This is all public knowledge. Just go out there and find the buildings that you admire, and go see them! For those of you not from New York City, look at the mortgage. That’s monthly.

The final step of this process before you get going, is to really try to understand the pro forma. You buy it for X, you put in Y, you sell it for Z. You can download some of these pro formas online, like the ones here form Guerrilla Development [see here]. You need to be able to go through them, take them apart, and put them together. And you need to do it again and again and again. By the time you go to a bank or an investor, you need to prove to them that you know what you are talking about and you know that they are going to get their money back, and they are going to make some money in the process.

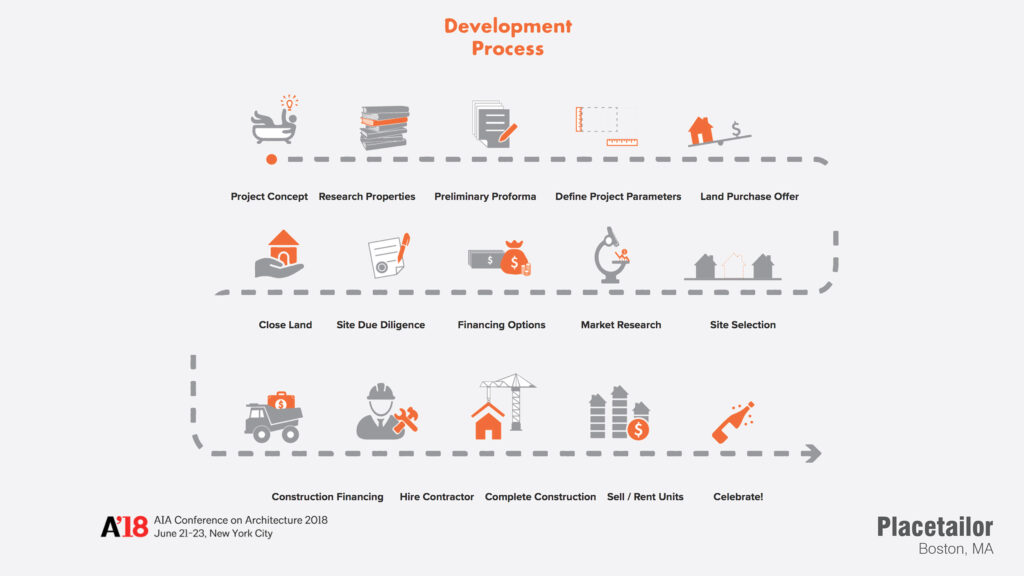

Placetailor put together this diagram. So that’s it! You rip off the bandaid. You figure out what you want to do. You figure out how much it is going to cost. You look up a site. You organize the finances. You close the site. You get a contractor, and you go make money! When you sell, the loan gets paid back, the investor gets paid back, and you get whatever is left in the end… if there’s anything left in the end. Which is a risk.

In the summer of 2011, a group of designers successfully completed a Kickstarter campaign to build a pool that also filters water in New York City’s East River. +Pool raised over $41,000 to become one of the first modern-day crowdfunding campaigns for architecture. Two years later, +Pool raised an additional $273,000 to be used for research in a second Kickstarter campaign and currently anticipates construction sometime in the near future. In the summer of 2015, a similar project in London, Thames Baths Lido, raised £142,000 on Kickstarter to build a pool in London’s River Thames. Extremely similar projects have since shown up in crowdfunding campaigns in Berlin, Chicago, Houston, Melbourne, and beyond. Most of these campaigns receive funds in excess of what they are searching for, yet it is rare that successful architecture campaigns are actually constructed. This begs two questions: what happens to that money, and can architecture be crowdfunded?

One of the first projects to be successfully built using crowdfunding as a financial mechanism is Luchtsingel, a 400m long pedestrian bridge in Rotterdam. In 2011, the architecture firm ZUS raised over €100,000 ($135,000 at the time) to develop the bridge by offering to CNC-route the name of any donor who contributed more than €25 onto planks of wood that would be used in construction. The crowdfunding campaign was successful because it showed local politicians both the public desire for the project and the willingness of the public to begin funding it. The local government subsequently contributed the remaining €4 million required for construction, and the project was completed in the summer of 2015. Crowdfunding was the catalyst for taking the architect’s initial idea and making it a reality.

In 2013, David Loewenstein, Philip Auchettl, and Jason Grauten were completing their thesis project for their Master of Architecture programs. Together, they proposed an urban park in downtown San Diego; the hipster-type with a dog park, biergarten, and concert venue that would exploit vacant city-owned land. After receiving a plethora of positive feedback from their proposal, they decided to give themselves six-months to make the student project a reality. They launched a Kickstarter campaign and raised $60,000 in the first 30 days to cover the initial administrative costs and to prove to private investors and the city that the community was serious about having such a place in their community. RAD LAB convinced the city to temporarily lease them vacant land on which a large condo development was scheduled to be built. David, Philip, and Jason then approached investors and raised funds to build the temporary project utilizing previously used shipping containers. They limited their initial capital costs by requiring each tenant to purchase the container and pay for the renovation using RAD LAB’s design. The tenant would then pay RAD LAB for the lease of the space, who would turn around and pay the city for the land. Completing the urban park took a lot of hustle and collaboration between the city of San Diego and many private investors, which Architect & Developer RAD LAB successfully mediated.

I sat down with Philip Auchettl of RAD LAB who discussed his experience. “We were going to be a placeholder for future development. We used shipping containers so we could pick everything up and move it to a new location. That way we could reactivate somewhere else when it came time to move. That was when people started to get excited. I think it made people in the community more open to the idea of it. Anything that is temporary, people seem willing to give it a go. Anytime someone wants to build a brick-and-mortar thing, people line up with their pitchforks.”

Kickstarter-type campaigns have created interesting ideas and possibilities, but few results considering the staggering amount of money raised. Donation-based crowdfunding can be used as a catalyst for obtaining conventional financing or government support, but what about crowdfunding architecture as an investment? Can an architect pull together small amounts of funds from various sources to finance a building? Up until recently the answer was “no.” The Securities Act of 1933 made it illegal to market shares of unregistered securities such as interests in real estate development, which meant that people seeking capital were unable to publicly state that they were raising money for investment purposes to finance a project. The JOBS Act changed this and made crowdfunding architecture possible.

In 2012, Congress passed the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act, more commonly known as the JOBS Act. This has allowed crowdfunding to permeate into real estate. You no longer have to rely on personal relations or country club connections to pull together a deal. You can put together an offering online that outlines a project you intend to develop with the intent of luring any investor, big or small. Prior to the JOBS Act, investors were required to have a net worth of $1 million or an income of $200,000 per year in order to participate in similar investments. Now, people of any income bracket are able to invest in a project, though there are limits set by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) based on a combination of net worth and income levels. By imposing these types of restrictions, the SEC tries to protect smaller investors from risks they cannot bare, which could have devastating effects on the economy if a large portion of the population were to take part in high-risk activities.

A recent report from the Cambridge Judge Business School has shown tremendous growth in real estate crowdfunding. In 2013, online platforms generated $43 million in investments. By 2015, this had increased to $468m per year. As the more than 125 American based real estate crowdfunding platforms gain momentum, serious money is being invested in real estate in a more grassroots way than we have ever seen before. The industry is still adapting and finding its groove.

Two exemplary architects have successfully used the JOBS Act to help finance projects: Kevin Cavenaugh of Guerrilla Development, and Jonathan Tate of OJT. Kevin recently completed his second successful raise, and completed construction on his first crowdfunded project, both located in Portland, Oregon. Kevin was interested in trying a new pathway of financing that would allow him to develop his projects without the bank meddling in the process. “In 2009, I was really mad at banks,” mentioned Kevin when I spoke with him about his work. “Crowdfunding was this neat way to minimize the seat at the table of the lender.” In his first project, the Fair-Haired Dumbbell, he raised $1.5 million from regular people who were not accredited investors across five states. To do this, he spent 15-months and $200,000 in attorney’s fees to successfully complete the required SEC process in order to crowdfund the project. It wasn’t easy.

Kevin’s second project, Jolene’s First Cousin, raised $300,000 in three days through a different route. Kevin took advantage of an exemption from SEC registration under Section 504 of Regulation D, which permitted him to raise money exclusively in the state of Oregon through the Oregon Intrastate Offering (OIO). This allowed him to avoid the expense and bureaucracy of the SEC, but limited him to pursuing investors within a single state. The second project also allowed him to test his suspicion that investors would accept a lower return of 5 percent if investors knew their investment would fund a social cause; in this case, low-income housing for homeless people. Jolene’s First Cousin was so popular that investors funded it in three days! Kevin has been able to prove that crowdfunding is a viable pathway to create a project. It required a lot of legal legwork, upfront costs, and time. It did, however, result in a viable financial path forward. This is real money. Big Money. Take a look at the Fair-Haired Dumbbell and Jolene’s First Cousin crowdfunding videos. They are really entertaining, and also explain how participating investors receive distributions and the risks involved in the investment.

Kevin used his own platform to crowdfund the equity for his projects. This required him to deal directly with the SEC, the OIO, and all the bureaucracy therein. Jonathan Tate used a different strategy. He partnered with a third party platform, Small Change, who was already accredited by the SEC to raise funds through Regulation D and Regulation CF, which are the new parts of the JOBS Act that have only recently been available. I sat down with Jonathan to discuss the work he was doing as an Architect & Developer. “The hopes of the Reg CF is that there is an enormous untapped investor pool,” mentioned Jonathan. “The point of the JOBS Act was to get everyday individuals involved in this. I do think there is a lot of potential out there, but it needs to build up some momentum and visibility. Most people don’t understand what this is.” By going through Small Change, Jonathan was able to limit his required involvement with the SEC. He only had to supply the offering information, and Small Change took care of the rest.

All three of these projects still used a construction loan from a local bank. Neither Kevin nor Jonathan used crowdfunding for the entire amount. The crowdfunding was used as the mezzanine debt in the capital stack. In each case, this limited the equity that Kevin and Jonathan would have otherwise had to supply. In Jonathan’s case, his capital stack was $20,000 of sweat equity, $95,000 of crowdfunding, and the balance in the construction loan. “Essentially, the money that we are asking for is the equity requirement for the construction loan,” explained Jonathan. “It is 20 percent of the construction loan. But the rest of it shows up as our own contribution. We have money in the land and in soft costs. We are not reimbursing our services until the end when we sell everything. There is a preferred interest for the investors, and then they get a share of the upside afterward.”

Regulation CF of the JOBS Act offers the best opportunity to crowdfund architecture today. Partnering with a platform like Small Change is the most strait-forward path to get started. Kevin, Jonathan, and Philip all love the architect as developer business model. It allows the architect to have more control and gives the ability to design not only the project, but the process. “I believe that we learn a lot as architects and as developers,” reiterates Kevin. Crowdfunding architecture is one of the most unique ways to act as an Architect & Developer. I believe that the crowdfunding sector of real estate will quickly explode to a point of saturation by standard mediocre developers. I hope that more architects lead the way for a better future.

For more information on architects self-initiating work, see the book Architect & Developer: A Guide to Self-Initiating Projects.

]]>

When Guerrilla Development opened up crowdfunding for its latest project, a two-building mixed-use development called Jolene’s First Cousin, the team figured there would be strong demand. An earlier project, the Fair-Haired Dumbbell (they have a penchant for quirky names to go along with their iconoclastic buildings), raised $1.5 million from 121 investors in eight months, using Regulation A.

But when the Jolene campaign hit its $300,000 target in just 72 hours in late December, even its developers were surprised.

Real estate has been one of the hottest segments of crowdfunding under the JOBS Act. Most real estate crowdfunding portals have shifted to REIT-style investing, which bundles many projects into one fund.

Jolene’s First Cousin stands apart—and not just for its name (which comes from an off-color, inside joke). For one, Guerrilla Development is well known in the community and its projects suit the idiosyncratic aesthetic of Portland, Oregon, where it is based. The project is relatively modest in scale, but it has an ambitious social mission: to help address Portland’s growing homelessness problem.

Democratizing Development

Jolene’s First Cousin, which recently broke ground and is expected to be completed by early 2019, involves the development of twin two-story buildings on a single lot in the heart of the Creston-Kenilworth neighborhood in southeast Portland. It will have three ground-level retail spaces and two market rate lofts that will help subsidize the project’s 11 single resident occupancy (SRO) rooms. The SRO rooms, which will share common space and amenities and rent for $425 a month, will be filled with the help of JOIN, a Portland-based nonprofit that helps the homeless transition to permanent housing. JOIN will also hold the master lease.

The success of the Jolene’s First Cousin campaign underscores how a unique venture and vision can resonate with investors who long to be part of something meaningful—and offers lessons for others looking to crowdfund similar ventures.

Guerrilla Development is a believer in democratized development, and that extends to financing. Everyday Oregonians were able to invest in Jolene’s First Cousin under a Rule 504 exemption of Regulation D, which was qualified by the State of Oregon. (The developer considered using Oregon’s intrastate crowdfunding exemption, but that exemption limits the amount that can be raised to $250,000).

The Class B shares, paying 5% interest, were offered directly through Guerrilla Development’s web site, using back-end technology from Portland-based Chroma.

“Everyday Portlanders”

In a few short days, 43 people snapped up the shares, nearly all of them from Portland. Even with a fairly high minimum investment of $3,000, 15 of the investors were unaccredited (meaning not high net worth individuals).

The $300,000 crowd investment was just a portion of the overall capital stack for the project, which also included a small group of accredited investors and a $1.5 million construction loan.

The crowd-investors will receive an annual 5% preferred return (uncompounded) for the next 10 years. A preferred return means they’ll be paid before all Class A accredited investors, but after the bank (bank loans are always paid first). In year 10, the Class B investors will receive both the return of their principal and a percentage split of the proceeds of a refinancing event.

Guerilla plans to build more Jolene development projects— a second, third, and endless stream of “cousins.” It will continue to carve out a role for crowd-investors, even though the projects could be funded entirely by conventional means.

“We want everyday Portlanders to be able to invest in their neighborhood and to enjoy returns that are likely better than they are accustomed to,” said Kevin Cavenaugh, Guerrilla’s owner. That includes “school teachers and mechanics” who would typically be excluded from such opportunities, he said. “It’s ethically important to cast a wider net to our investor pool.”

“There is also a community empowerment component to crowd-investing. Instead of just telling someone what is going to be on their street corner, this is a chance for them to make money while being involved with the active development of their neighborhood,” added Cavenaugh.

Finally, he said, homelessness is a hugely pervasive issue in Portland, and “creating an avenue of action through crowd-investing is a way for concerned citizens to contribute to solutions (and make a profit).”

Here are some of the potential success factors and lessons learned from Guerrilla Development:

Topical Issue: Jolene’s puts a spotlight on Portland’s growing homeless problem, allowing people to invest in a tangible project, be part of a novel experiment, and use their investment dollars for social impact.

Reputation: Guerrilla is known for designing interesting spaces that are very visible in the community. It has a successful track record and a reputation for being radically transparent and creating models others can follow.

Existing Investor Pool: For Jolene’s, Guerrilla was able to tap into an existing pool of Oregon investors from its Fair-haired Dumbbell project, a popular development and well-known crowdfunding campaign. About half of Jolene’s 43 investors were also investors in the Fair-Haired Dumbbell. Those investors have already begun receiving distributions—approximately $120,000 was paid to FHD’s unaccredited investors in 2017—lending further validation.

Marketing: Guerilla’s clever and engaging marketing for FHD, along with a well-publicized campaign, may have paved the way for more efficient fundraising for JFC. Marketing is delivered via channels their audience is already in, such as sending snippets via Instagram.

Relationship with Regulators: Guerrilla’s relationship with regulators was a critical factor in the success of the offering. State regulators communicated openly and proactively and were open to reasonable ‘no-actions,’ including waiving restrictions on public advertising and general solicitation (with pre-approval of material by regulators), waiving of escrow requirements (Guerrilla instead was allowed to segregate the investment dollars in a separate bank account at an approved institution), and flexibility on the structure of the offering.

Solid Technology Partner: A good tech partner or platform is key. In Chroma, Guerrilla found a collaborative partner that customized its tech platform for Guerrilla and helped to keep costs low. It also shares Guerrilla’s ethos.

With two crowd-financings under its belt, Guerrilla Development offers lessons for others contemplating a crowdfunding campaign.

First, raising money this way is not for the faint of heart. Community investment is a cornerstone of how Guerrilla finances its projects. However, the cost of pulling together the actors is not cheap or easy. For example, it can be difficult to find a lawyer who understands or is interested in crowdinvesting regulations. (Guerrilla worked with Kyle Wuepper of Brix).

Keeping costs low enough to be viable and repeatable is challenging. At around $45,000, the cost of capital was not cheap or easy for Jolene’s First Cousin, but Guerrilla hopes it will become simpler with future raises. However, should Guerrilla decide to change the vehicle or platform, those efficiencies will not be gained.

Finally, it’s critical to have an engaged community and marketplace in order to be successful.

See more about Guerilla Development and Kevin {here}.

]]>

In July 2017, I spoke with Architect & Developer Kevin Cavenaugh of Guerrilla Development in Portland, OR. See more information about Guerrilla Development at guerrilladev.co. See more articles about Kevin {here}.

Kevin Cavenaugh: I knew that architects would toil for years making super-low money. That is all fine, but the bad part was that the work wouldn’t be inspiring. We would toil a decade before we had any design opportunities. So I was getting paid a shitty wage to do shitty work. It didn’t seem fun, but I loved Architecture. I wanted to design buildings. So I moved to Sacramento, which at the time was a pretty pitiful town. This was thirty years ago. I bought a house for $51,000. I could do that with my $10 per hour architecture salary. It worked. I knew real estate was going to augment my salary as an architect and make me a better architect in the process. So I bought a house and fixed it up. It was a beat-up house in a beat-up neighborhood. I learned a lot. Once you do one, it didn’t take long until I had done a couple of dozen.

Buying and fixing up a house is no different than commercial real estate. It is the same basic concept. You own the property. You buy something for A. You spend B fixing it up or making it more valuable. When you are done, if it is worth more than A+B, then you succeeded. If it is worth less than A+B, then you failed. It is that simple.

James Petty: As you were working on these projects, were you trying to get a little bit bigger and a little bit bigger?

KC: Well at the end of a couple of dozen houses I realized that I was a restorer. There wasn’t any design work in renovation. I was doing really neat turn of the last century houses. I was learning a lot about construction and historic detailing. Even as a 30-year old, no one knew I had any design skill at all. I had a feeling that I did, but I wasn’t even sure. Back then I slowly realized that while I had my day job at an architecture firm, the people that were sitting across from me at the table, the client or developer, were not necessarily smarter than me. They just had control and were calling the shots. I took a couple of them out for coffee and asked them questions about the industry. That was when I realized that fixing up houses was no different than what they were doing. It helped demystify the idea of development. I already had a risk appetite because I was fixing and keeping houses as rentals. I was renting them because once you make something, it is hard to give the keys to someone else.

JP: Would that help you finance the next project?

KC: Yeah. I would only sell when I had to refill my coffers. It was frustrating because I was still a 34-year old designer. I was doing rather tedious work at a mid-size architecture firm here in Portland. I was tired of becoming a restorer of these houses. I needed to prove to myself whether or not I could design. I thought I could. So I took two of my rental houses, and I sold them. With those proceeds, I bought a piece of commercial property. I went to my bosses. I knocked on their office doors and said, “Hey, is it OK if I hire you? Can I be the client and the employee at the same time? Do you mind?” They had nothing to gain because it was such a tiny job. It was a 54-foot

by 100-foot corner lot in a neighborhood that was on the east side of Portland in kind of a non-location. I saw it had potential. It was affordable. I bought it for $168,000. So I asked them, “Can I hire you? But can I work

on it here in the office?” I am not a licensed architect, and I couldn’t moonlight. I had two young kids. That is the last thing you want to do, work 40-hours and then come home and then work more. I am innately a lazy man. I don’t think I have ever worked more than 40 hours per week in my life.

The only reason I brought it in was so that I could do my own design. I needed the firm’s help on the technical side, the detailing, and code analysis. So I designed what is now the Box + One building. It was strange. I would draw it and draw it and draw it. I would get a paycheck once per month, and then I would get handed an invoice for three-times the amount of the paycheck at the same time. But it worked. The budget allowed for an architecture fee. I had a bank loan, and I owned the land free and clear.

JP: Finding the initial capital always seems to be the biggest hurdle. That is the complaint I hear the most.

KC: That is exactly right. Initially, I used smoke and mirrors and leverage. I had some money from the real estate so I could juggle properties to create assets and create a path forward on my first project. So I had no investors then. Post-recession I have investors for all my projects.

JP: Are you contracting out other architects to create your drawings?

KC: Yeah. Every morning I go to the coffee shop and get out the same recycled brown napkin, and I sketch what I am working on that week or month. By the time I hand the napkin to the architect, it is pretty tight with dimensions. It is more than what I call Phase Zero, which is just the program. It’s fun! It is everything that you want to do. Now in my career, I get to choose what I do. I get to draw the fun stuff and then I can pick and choose which architects I want to work with. The only reason I put my name on the dotted line and take on massive debt and massive risk is so that I can do the fun part.

JP: How does Guerilla Development make a profit?

KC: We don’t have clients. I don’t want clients ever. The last clients I had were my parents when I was designing their house about eight years ago. They fired me. Clients get to decide Phase Zero, and they hire me at Phase One.

Someone always tells us what Phase Zero is. I look at that and think, “I would rather do family-size units and surround it with a garden and see if the finances work.” They would not give us that opportunity. Everyone else always decides what Phase Zero is. It is boring as hell to me. I don’t want someone hiring me to design X for them; I want to decide the X.

I keep all of my projects long-term. When they fail… and every single project fails… I just fix it. I get a letter from the tenant telling me they have a leak in their space. We manage our own properties. So I email it over to the guy in the desk next to mine. He is the asset manager. He runs over and fixes the leak or hires someone to fix it. When he gets back, he will tell me that one of the details was a shitty detail and that we shouldn’t do that detail that way anymore. We should do something different. We are always getting better as architects.

JP: That is a great feedback loop.

KC: If you hired me to be your architect, and there was a leak, I am not getting a letter from a tenant; I am getting a letter from your lawyer suing me. If I were your architect, I would be a lot safer and a lot less experimental with my design hand. That sounds horrible. To answer your question, 100 percent of what keeps the doors open is based on our developer fees and our management fees. With long-term ownership, all of the properties are spinning off income. We have three different ways that we are generating money. Two of them are active, and one of them is passive.

JP: So this Fair-Haired Dumbbell project… It is a big showstopper. Everyone is curious about how you are using crowdfunding. Can you talk about working with the SEC and how you used the JOBS Act to get this going?

KC: There was a lengthy timeline, and it was a circuitous random winding road. In 2009, I was really mad at banks. Crowdfunding was this neat way to minimize the seat at the table of the lender. So, of course, I was curious about that and I wanted to figure that out. I met with Fundrise. Portland was a city that they liked and fit their model. So they said, “Let’s do this! Once you get all the paperwork taken care of and a blessing from the SEC, we will make a go of it.” I did that. It took me fifteen-months and $200,000 to get through the SEC paperwork. Then I went back to Fundrise and I said, “OK, I’m ready!” They turn and go, “Oh crap, we don’t do that model anymore. We are a much bigger company than when we met with you. We went out and raised money. Gosh, we feel bad… but sorry.” What do I do? I finally have this paperwork signed by all of these states. I had already done all of the hard parts, but now what do I do? So I decided to host the offering myself on my own website. I raised 1.5 million dollars. It was crazy. It took me a while. I put the word out and we self-promoted.

JP: I have seen the video! It was amazing!

KC: The SEC actually had to bless the script on that. There are laws on what you can say and what you cannot say. So we took that video, and we raised a shit-load of money. The most money that we raised was when we were on the front of the business page of the New York Times. Once that hit, then we made it. $800,000 of the $1.5 million was in the three weeks. I would do it again.

JP: Was the SEC approval for the project specifically, or for Guerilla Development for multiple projects?

KC: It was project-specific. So we would have to go through that again. If I can do it in half the time, and for half the legal fees, then it would be a model that is worth it. If I couldn’t, then it wouldn’t.

JP: The JOBS Act is still relatively new, and the government is slow to adapt to new things. Do you think as time passes by, that the process with the SEC will become smoother?

KC: With the Fair Haired-Dumbbell, I could, in theory, raise money from any state. At the end of the day, I need to pick and choose which states I accept investors from. I only chose five states. Each state has their own specific demands. For example, New York State wanted specific things from me that I wasn’t willing to do, so I chose not to take investors from New York State. Same thing for Texas. Both had a lot of interested investors. But at the end of the day, I could not get them to the table because of the regulatory hoops. But I took Washington, Oregon, Massachusetts, California, and Washington DC. That was enough.

I am currently doing a crowdfunding project, which is an unsubsidized mixed-use development. One of the units is an eleven-bed homeless SRO project. It is a profitable project and a tiny little infill project. I believe that we learn a lot as architects and as developers. Politicians should not put an entire population of poor people in one building with one address. Just think of Pruitt-Igoe. Efficiency is rarely the right long-term answer. So I have a project that helps that. It is cheaper than the city can provide homeless units for. The city pays on average $600 per month for providing housing, and without subsidy, we are offering rent for $400.